A downloadable, printable version of this story (pdf) is at right:

Privately published, 2020. Bill Jeffway.

Emerging Voices: Recovered stories beneath the well-worn stones at Milan’s Turkey Hill

Lives of a Revolutionary War Veteran, Former Slaves, Revealed

Out of respect for the lives of those whose story has been obscured over time, the Town of Milan (pronounced MY-lun) Bicentennial Committee sought a more complete history of its early communities of color in 2018, the bicentennial year of the town’s incorporation.

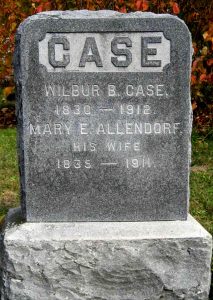

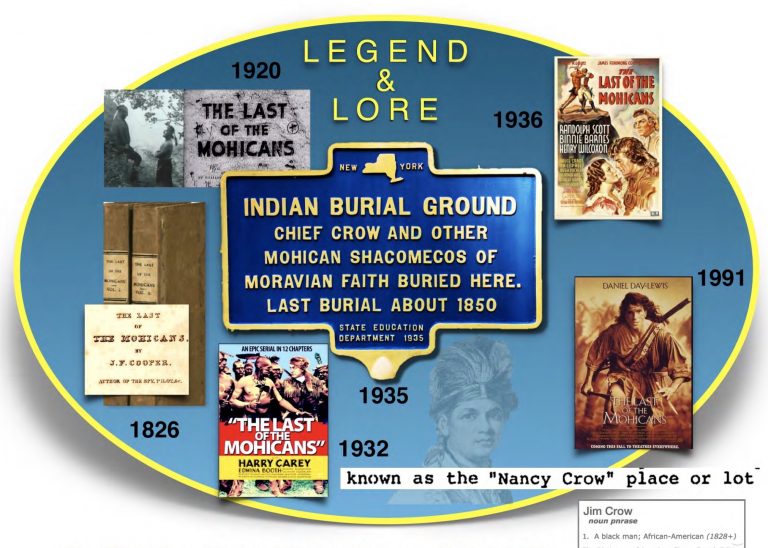

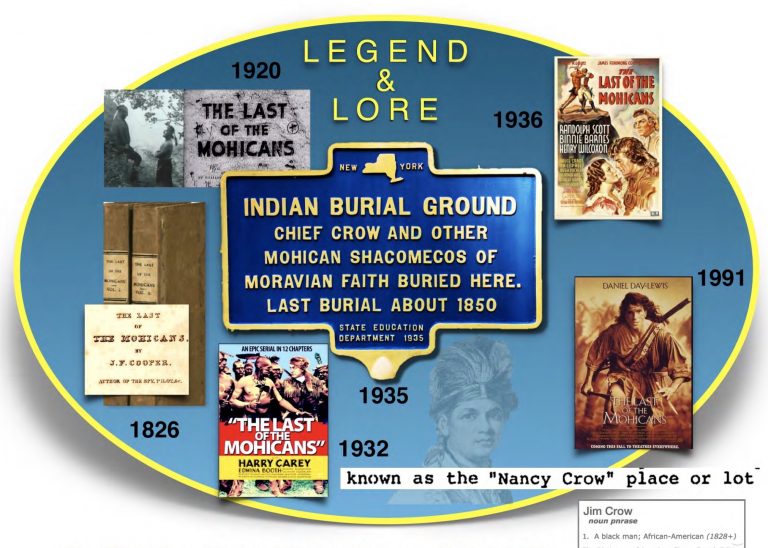

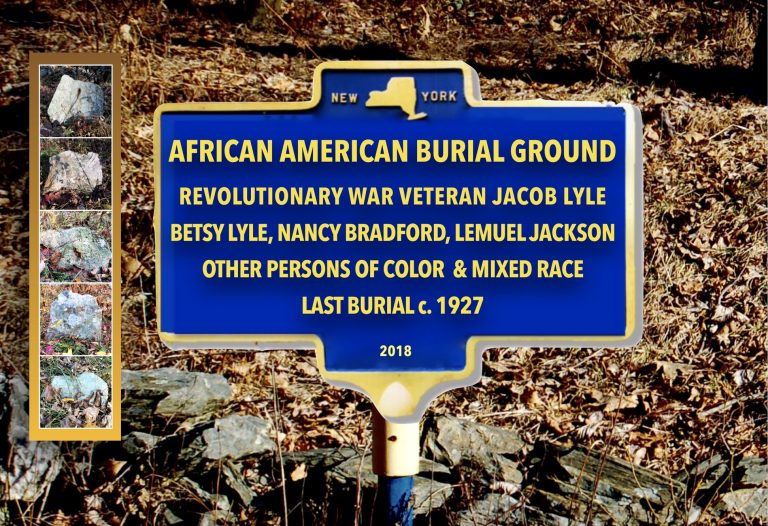

Some of the stories were revealed in a small burial ground beneath a handful of rough, blank stones surrounded by a triangular stone wall. It was popularly (but incorrectly, it would turn out) known as the “Indian Burial Ground” given the prominence of the classic 1935 NY State roadside historical marker declaring it as such. In this case we find the stories of a Black Revolutionary War veteran and his wife, and former slaves of Red Hook’s Martin family, as well as others.

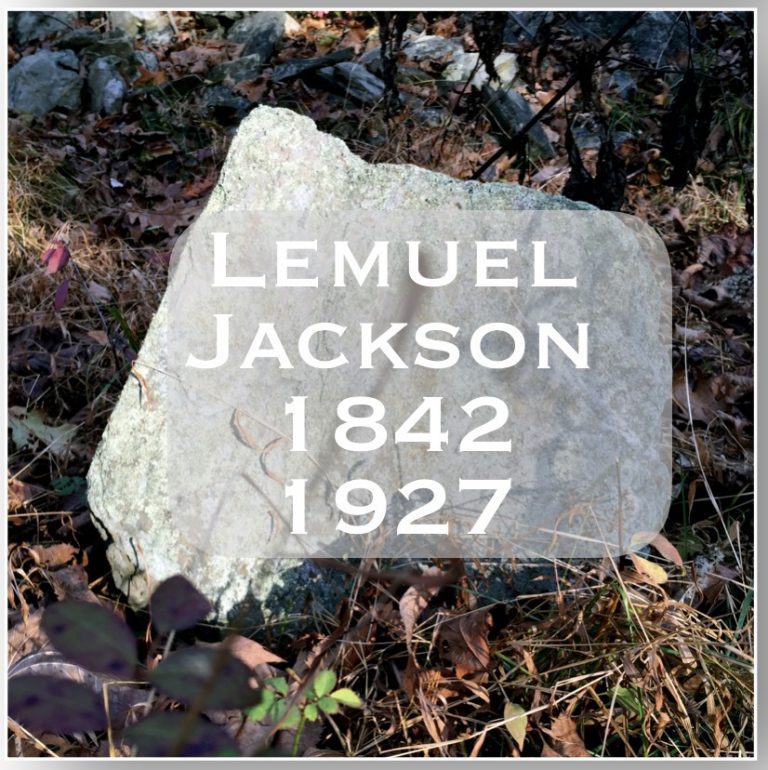

Finding evidence of the remains of these individuals is challenging because of the 19th century practice of burying persons of color not only separately, but with temporary or no markers. In Milan, this lasted until at least 1927. Milan Town Historian at the time, Bobbie Thompson, was the first to seriously question the claims of a Shekomeko “Chief Crow” being buried there in the 1970s.

There were Native American populations in the area. They were transient hunters for several thousand years before Henry Hudson sailed up what we now call the Hudson River in 1609. A kind of border area, the Mahican lived to the north, the Wappinger or Delaware lived to the south. Nearby Bard College Archaeology has done a number of assessments and discoveries in the immediate area supporting this. After 1609, Dutch, then English, settlers followed. Both of whom brought in enslaved Africans.

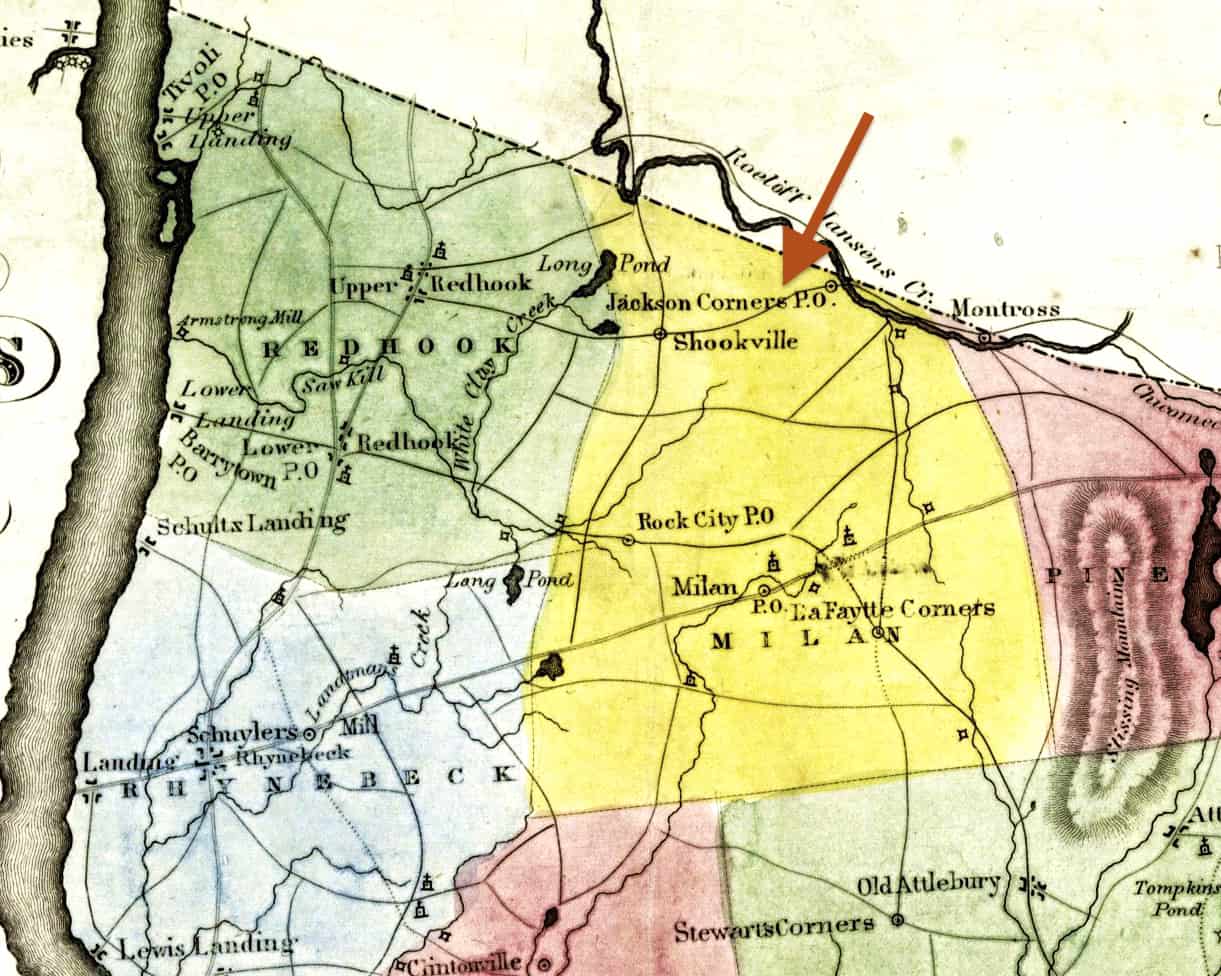

Above: The burial ground discussed here is on a main road connecting Red Hook on the Hudson River and the mines of Salisbury, CT. Map, Burr, 1839.

Above: Evidence of transient Native Americans in the immediate area for several thousand years before European contact is show here, courtesy Bard College Archaeology.

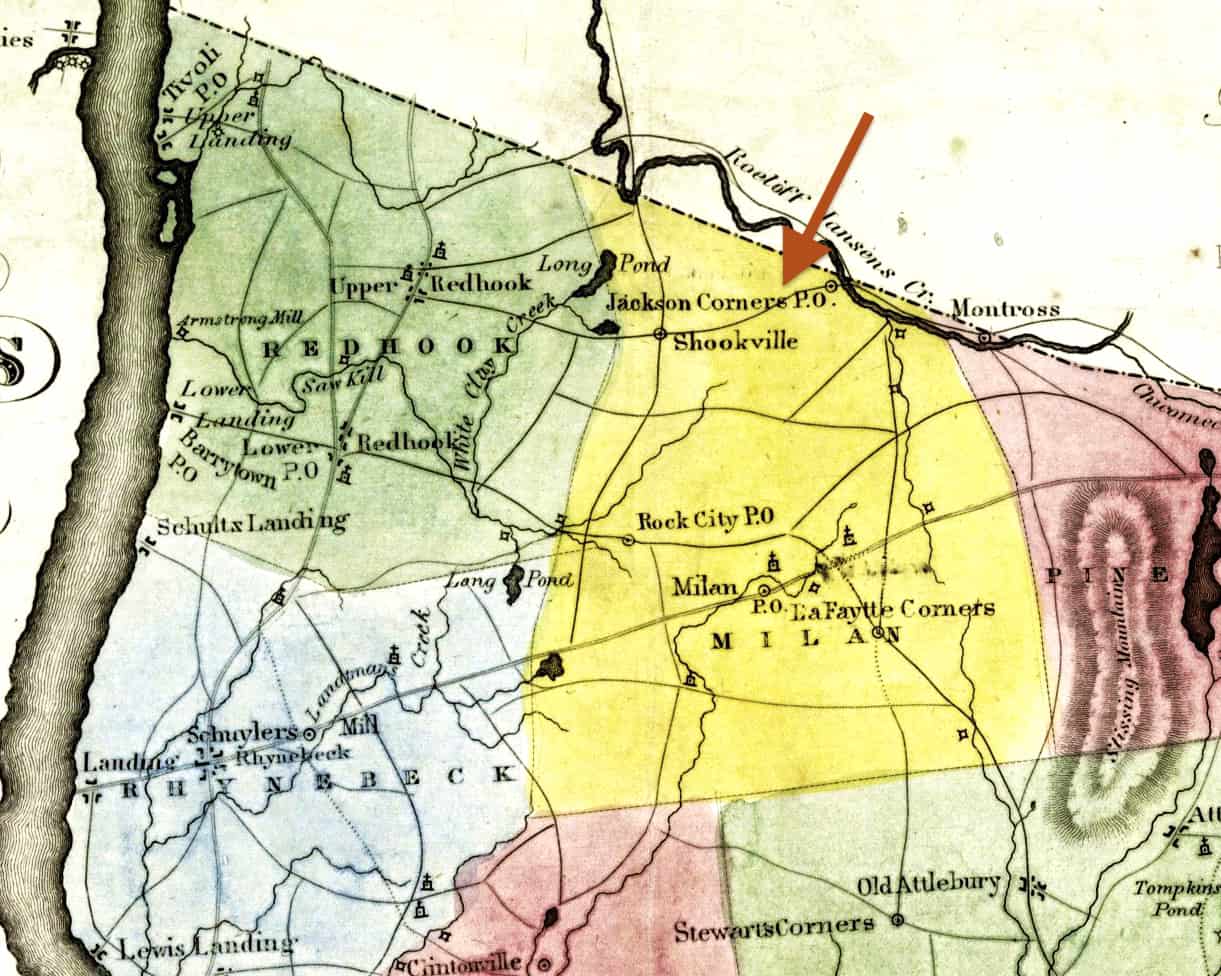

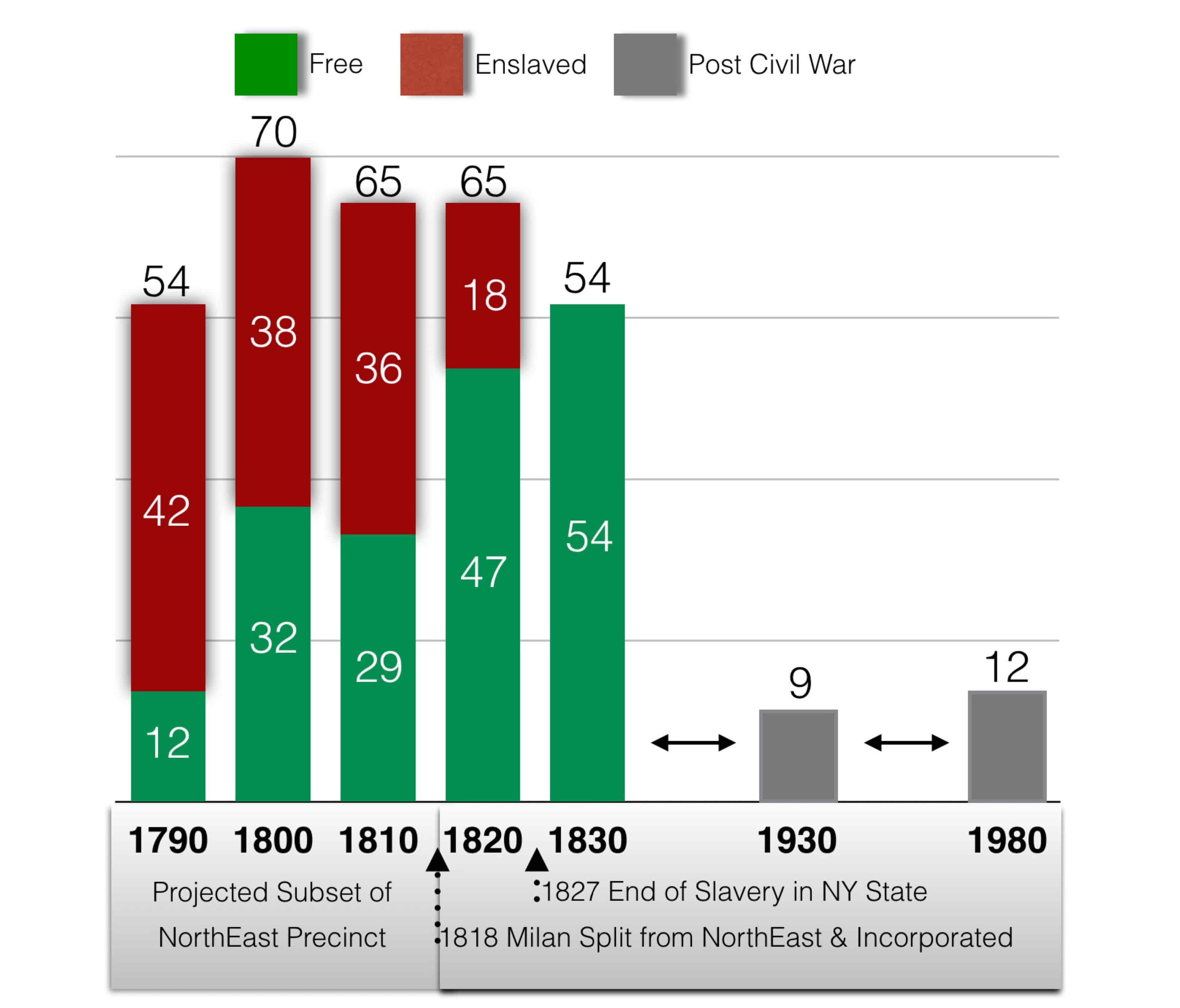

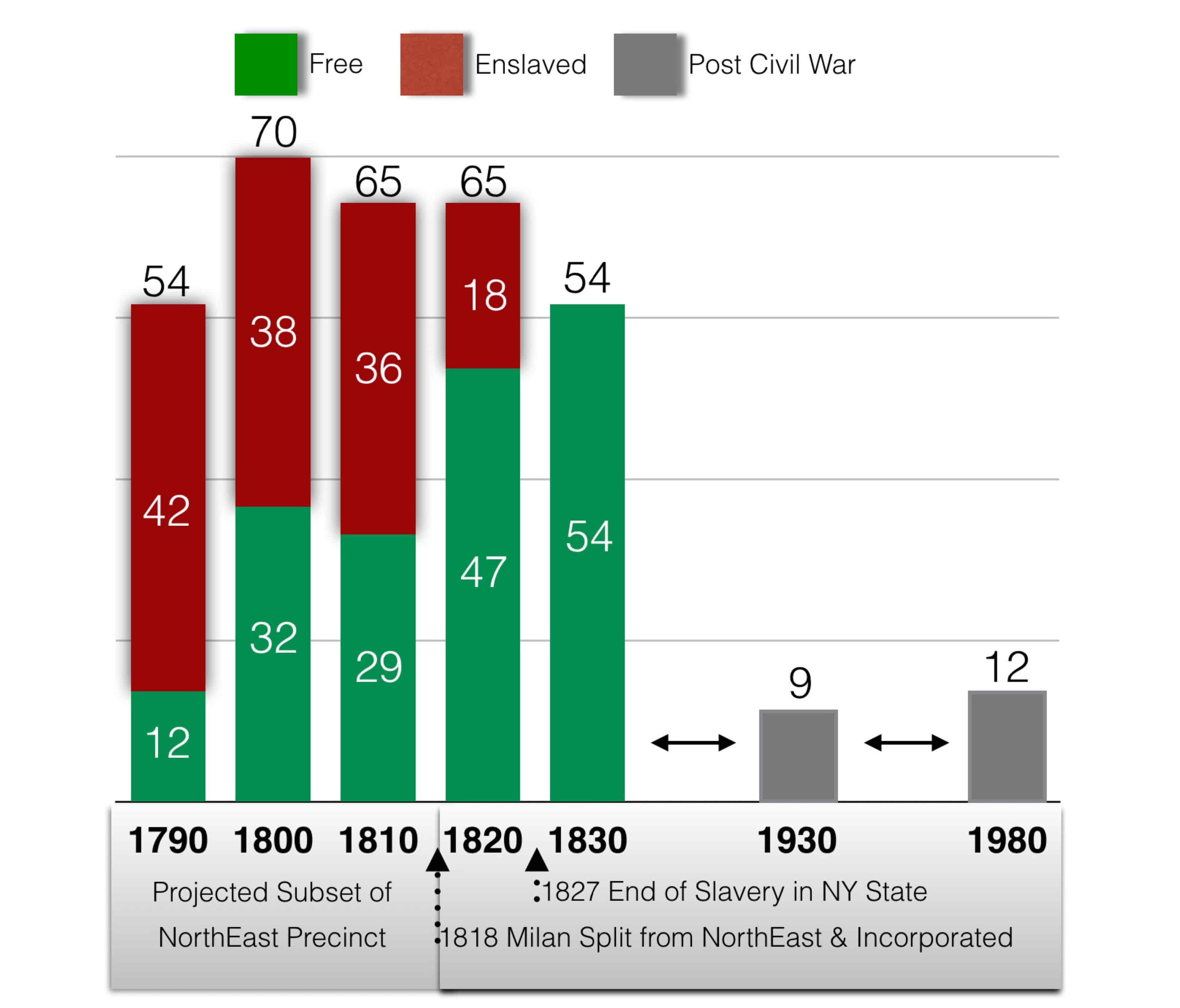

Dramatic population decline of Persons of Color

The population of rural Milan reduced dramatically after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. Following patterns elsewhere, its Black population declined after the Civil War

Mid-way between New York City and Albany, Europeans started to settle in the area of Northern Dutchess County in 1760, with enslaved Africans. Less likely to be Dutch who had already settled in areas like New York City and Albany, these settlers were more likely to be German Palatine, English, or Scots-Irish. The town was incorporated in 1818. Slavery was abolished in New York in 1827.

With the opening up of the west and migration to cities between 1820 and 1930, the population of rural Milan dropped to one third its size; from 1,846 to 622, accelerated by the global economic depression.

In 1820 there were 65 persons of color, the majority of whom, 47, were identified as “free colored,” while 18 individuals were noted as enslaved. Earlier census records showed about the same number of persons of color, but the percentage free vs. enslaved was reversed. By 1930, there were only 6 persons of color in the town. They were aging descendants of two of the early founding families, the last of whom died in 1952. It was at this nadir of population in the 1930s that identity of the burial ground was changed from “Colored” (largely meaning African American but including mixed race) to “Indian,” despite burials of African Americans as late as 1927.

Three known segregated sections for burial of Persons of Color

The town knew of one location for burial of persons of color. “Section E” of the cemetery in the adjoining town of Rhinebeck was established in 1853 for this purpose. The town learned of a second location, the southeast corner of Yeoman’s cemetery in Milan. Oral histories and the discovery of newspaper references led us to understand that burial of persons of color took place in this section, allowing only wooden crosses or no marker. Not a single headstone stands. Finally, the stories of those truly buried in this third place were recovered. Within a 1-acre parcel on Turkey Hill, there is a 1,000 square foot area right at the road that is enclosed by a stone wall. Today it has five visible stubs or headstones. There were eight stones visible in the 1970’s.

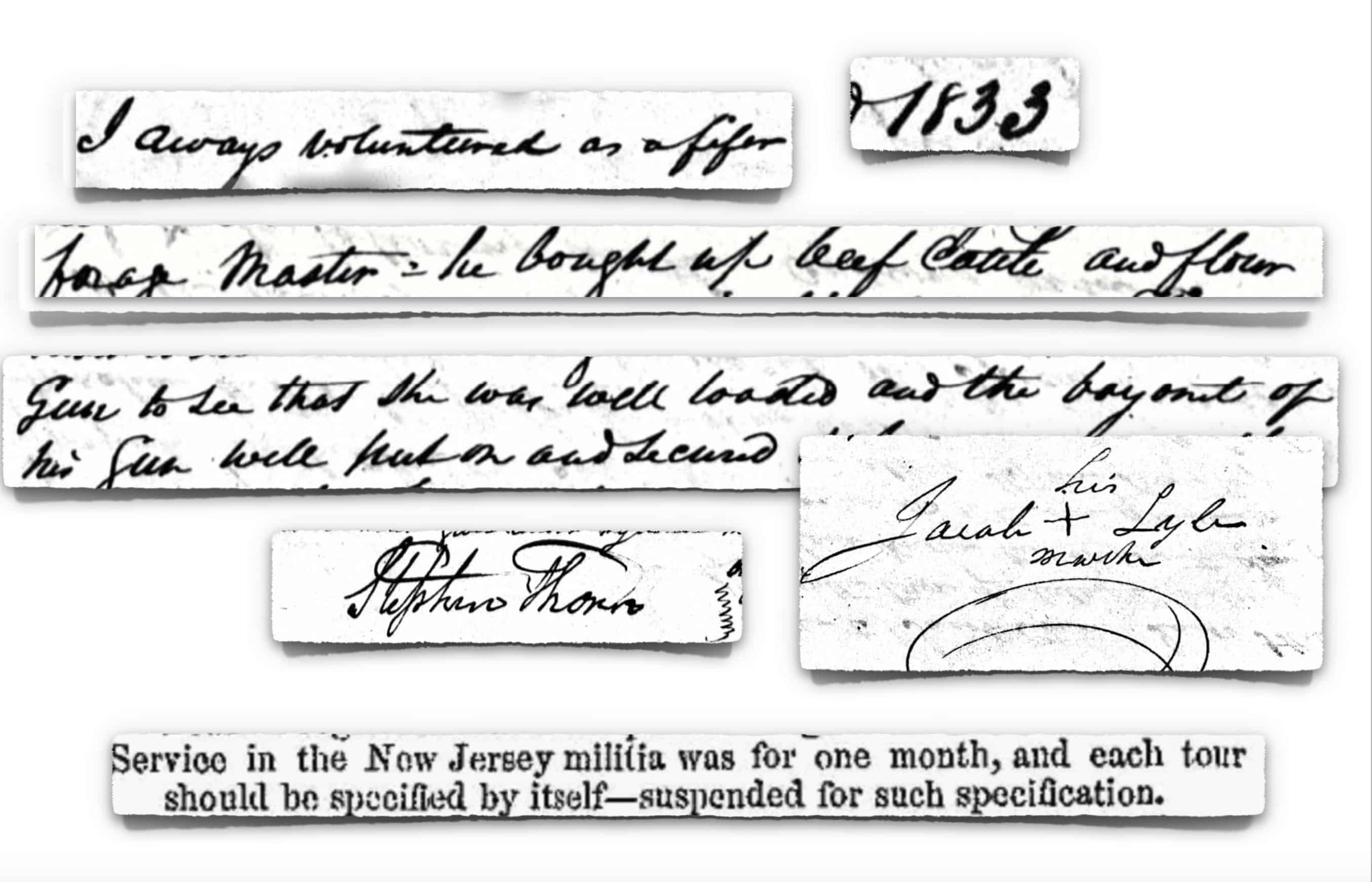

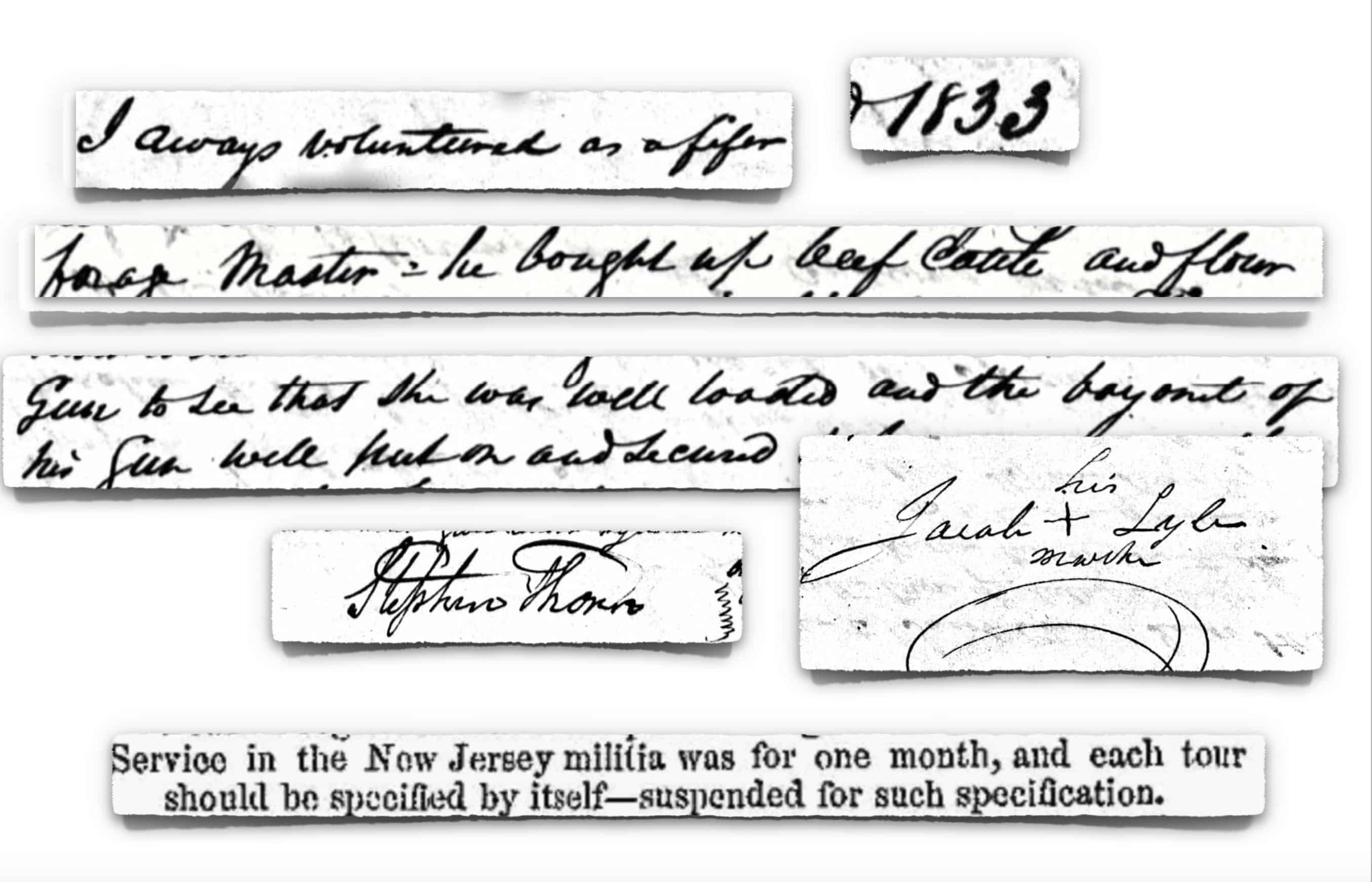

We know a great deal about Jacob Lyle because of dozens of pages from his Revolutionary War Pension application that remained suspended on his death aged in his 80s. Suspended for lack of detail, Lyle cited old age, lack of education, illiteracy, and poverty as reasons he could not fulfill the details sought despite sworn testimony from some of the most distinguished residents. He served 1 month in 1776 or 1777, 11 months in 1778, 10 months in 1779, 4 months in 1780, 4 months in 1781 and 1782.

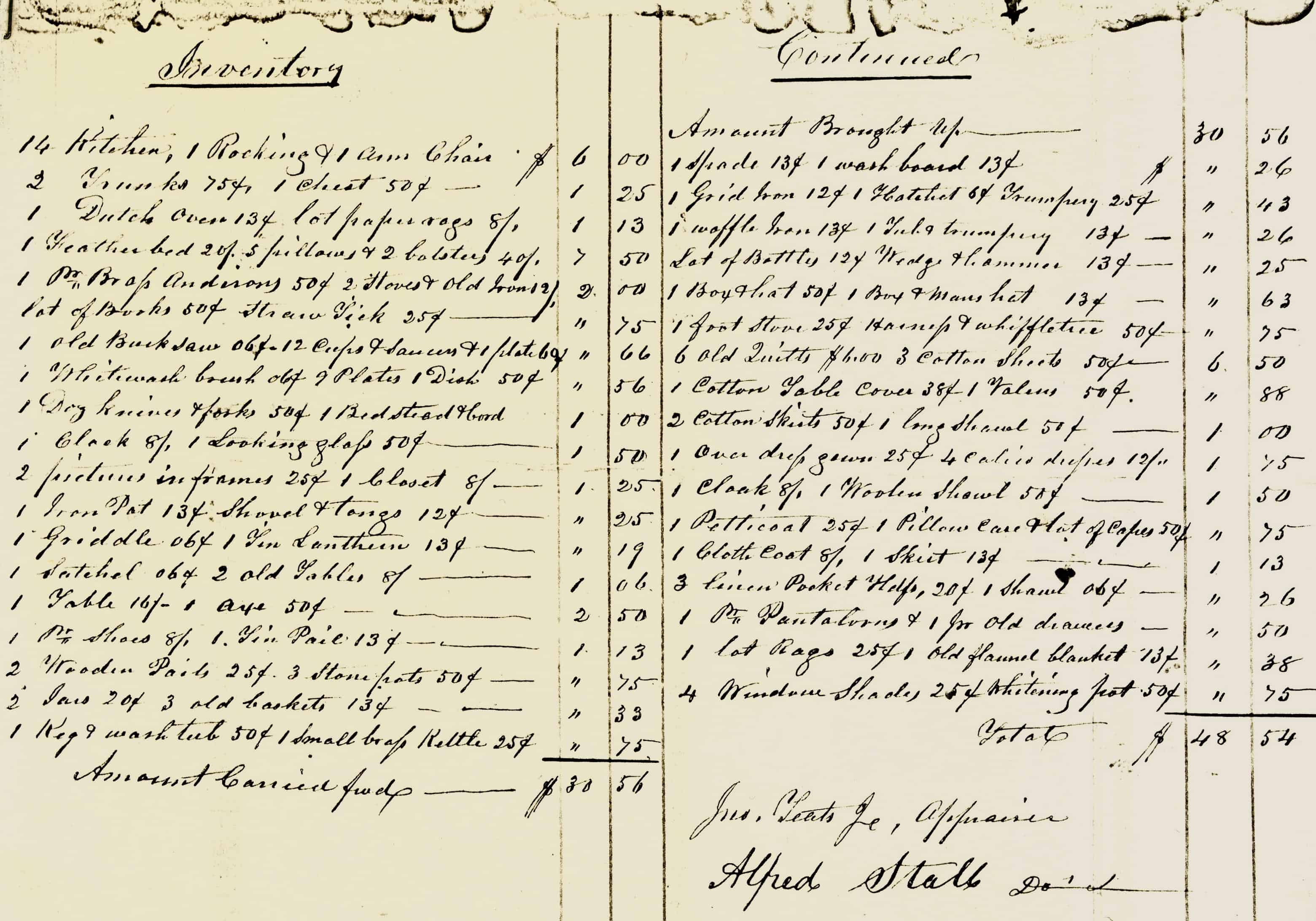

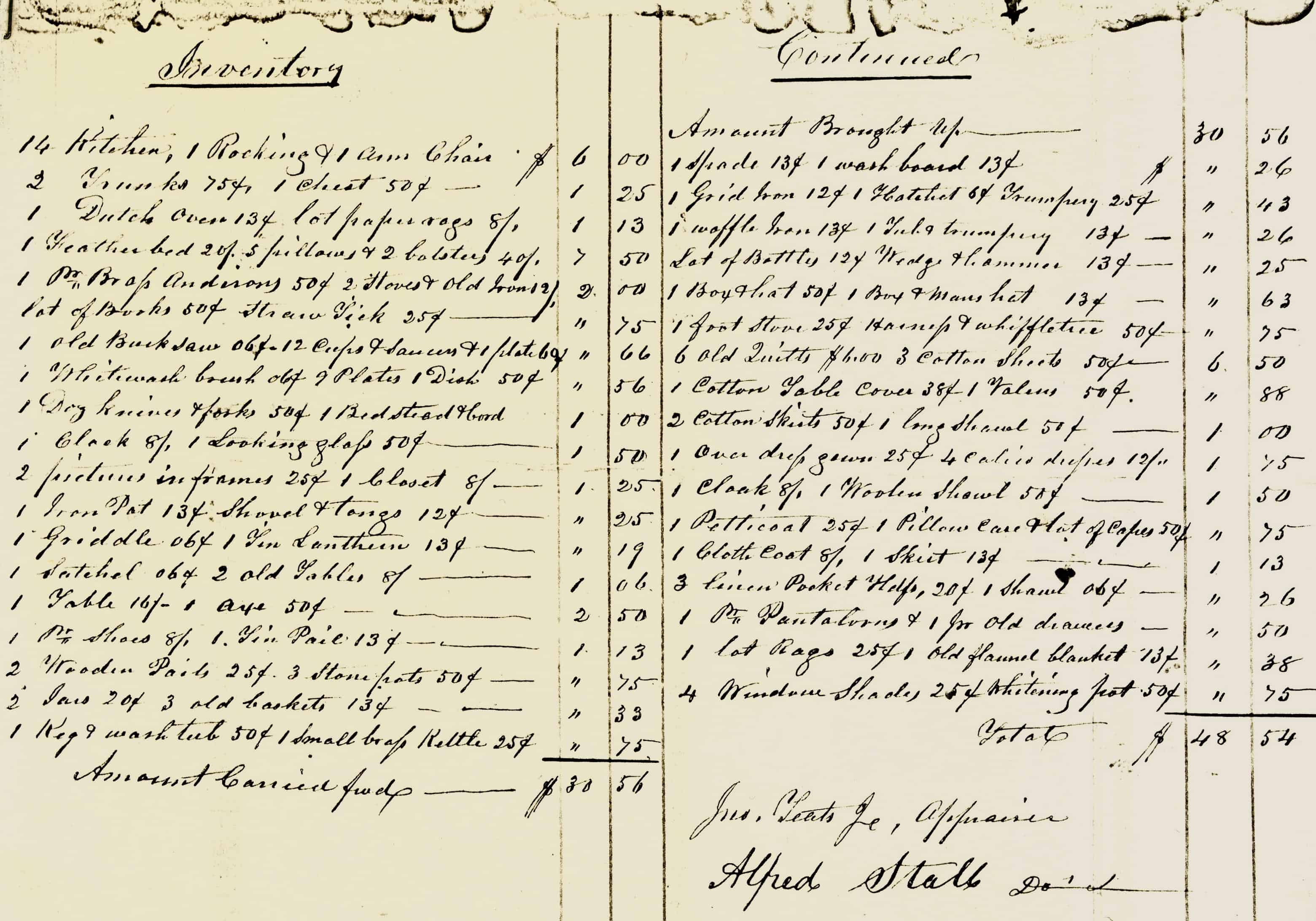

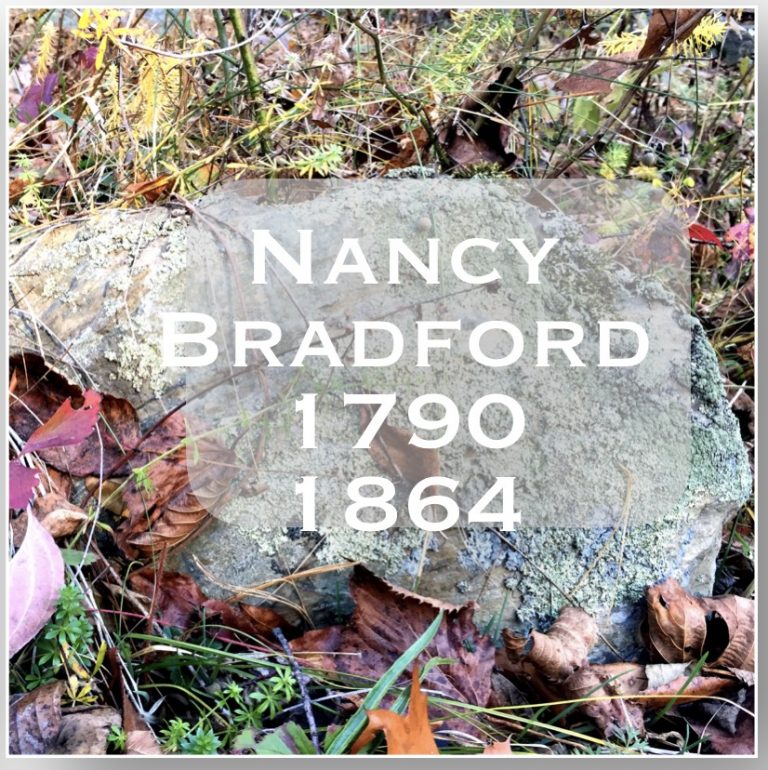

Nancy Bradford was a Black cook from Albany who bought an adjoining small lot. She ultimately took over the Lyle lot when they could no longer pay their mortgage. This is an inventory of her estate after her death in 1865.

Below: Excerpt from contemporary deed.

Did “Chief Crow” emerge from “Jim Crow?”

Understanding the past can be challenging enough, but in this instance the histories of Persons of Color were intentionally under-recorded. So we need to make assumptions which will be clear about. In addition to census records, we rely heavily on newspaper accounts, given the lack of official documentation.

Leaving aside, for the moment, the fact that there is a 1935 NYS Education Department historic marker which we will address later, the history of land ownership tells the story. The 1-acre lot was purchased in 1813 by Jacob Lyle and his wife, Betsy, both of whom are identified as Persons of Color in census records. Jacob served in the Revolutionary War in his home state of New Jersey. We know this through dozens of pages of sworn testimony in pension applications. We believe Jacob and Betsy Lyle both died in the 1840s, aged in their 80s. But we are not certain of the exact year. We believe they were buried on their homestead as was the practice of many at the time, and that this was the start of the “cemetery for colored people” as it was called in the early 1900s. There are several similar, extant. roadside, home cemeteries nearby.

The lot was subsequently owned by a women indicated as “Black” in census records. Nancy Bradford had bought a similar, small, adjoining lot after the Lyle’s had bought theirs. She came to own both after the death of the Jacob and Lyle. She died in 1865 and we believe she was also buried in the burgeoning cemetery. As a matter of fact, we feel certain because the property deed, even today, references the cemetery as “Nancy Crow Lot or Place.” We believe “Crow” is used in this instance as a racial epithet to describe African Americans, a use common for a half-century from 1840 in the north, according to the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Michigan. We believe Nancy Bradford’s “lot or place” became known as Nancy Crow as a result of the cultural impact the dance sensation of “Jim Crow” in New York from the 1830s.

Recast as “Indian” Burial Ground in 1934

Now a word about the New York State historical marker. On October 8, 1934 , Edith Harrison (sometimes Mrs. C. V. Harrison), submitted one of what would be a total of over 100 successful historical marker applications to New York State. The sign today reads, “Indian Burial Ground. Chief Crow and other Mahican Shacomecos of Moravian faith buried here. Last burial about 1850.” In terms of historic significance and sources she notes, “Last Indians of this section buried here,” and “Old men of this section tell of their grandparents seeing these daily and of their burial in this place.” A Chatham Courier article of June 28, 1934, four months before the sign application, reports on a historic meeting hosted by Mrs. Harrison at her home where the story of Chief Crow was told.

Above: The Chatham Courier, June 28, 1934, reports of a recent “historical meeting” hosted by Mrs. C. V. Harrison. Harrison was the successful petitioner of NY State Education Department for a historic roadside marker. The program was begun in 1925 in recognition of the 150th Anniversary of the American Revolution.

Above: A page from Mrs. Harrison’s October 8, 1934 application for the sign indicating her supporting documentation as “Old men of this section tell of their grandparents seeing these daily…” which correlates to the Chatham Courier story of a few months earlier. Courtesy of Bobbie Thompson, from her initial research in the 1970s.

Understanding The Story of Chief Crow

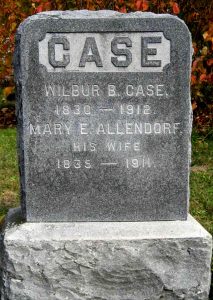

At that meeting, Herman Case tells the story that he says was frequently told by his mother. In summary, Mary Allendorf (1835-1911) was frightened as a small child by the “war whoop” of old Chief Crow. The article reports that the Chief lived in a wigwam (later referenced as a log cabin) given to him to live in after he sold land to white settlers. Seeing her cry, the Chief swept her up in his arms and took her to school. The article goes on to report that the Chief was married to a woman named Nancy, who was, of course, Nancy Crow. The story goes that they are buried in the “Indian cemetery” and that is why it is called, “Nancy Crow Lot or Place.

There are several technical difficulties in the story, such as Chief Crow being old enough circa 1840/1845 to have sold land to white settlers, but young enough to make a marathon run to the school carrying young Mary. It is entirely possible that Mary Allendorf told that story. And it seems certain that Herman Case told it in 1934. The “Shacomeco” reference is to a well-documented Moravian mission set up to convert Native Americans to Christianity that existed from 1742 to 1746. It was located fifteen miles to the southeast of this cemetery in what is now the town of Pine Plains. The mission was ordered to disband and persons ordered to leave the colony of New York as it had come to be perceived as a group (without evidence) that was conspiring with the French and “Papists.” Between the ban and threats of assassination from some locals, the mission was completely shut down and evacuated in 1746.

The timing, then, of 1850 burials of those from the mission is hard to reconcile.

Mary Allendorf Case took the story of Chief Crow to her grave in 1911.

A closer truth

A romantic notion of the “last” of the local Native Americans is longstanding

James Fenimore Cooper wrote The Last of the Mohicans in 1826 and it was turned into a movie in 1920, in 1931, 1936, and 1991.

Artist rendering of a sign that would be closer to the truth

The first owner of the small, triangular shaped piece of land, was a New Jersey veteran of the Revolutionary War, Jacob Lyle and his wife Betsy. It was common practice, with other examples nearby, that people were buried on their own land.

Burial of former slaves

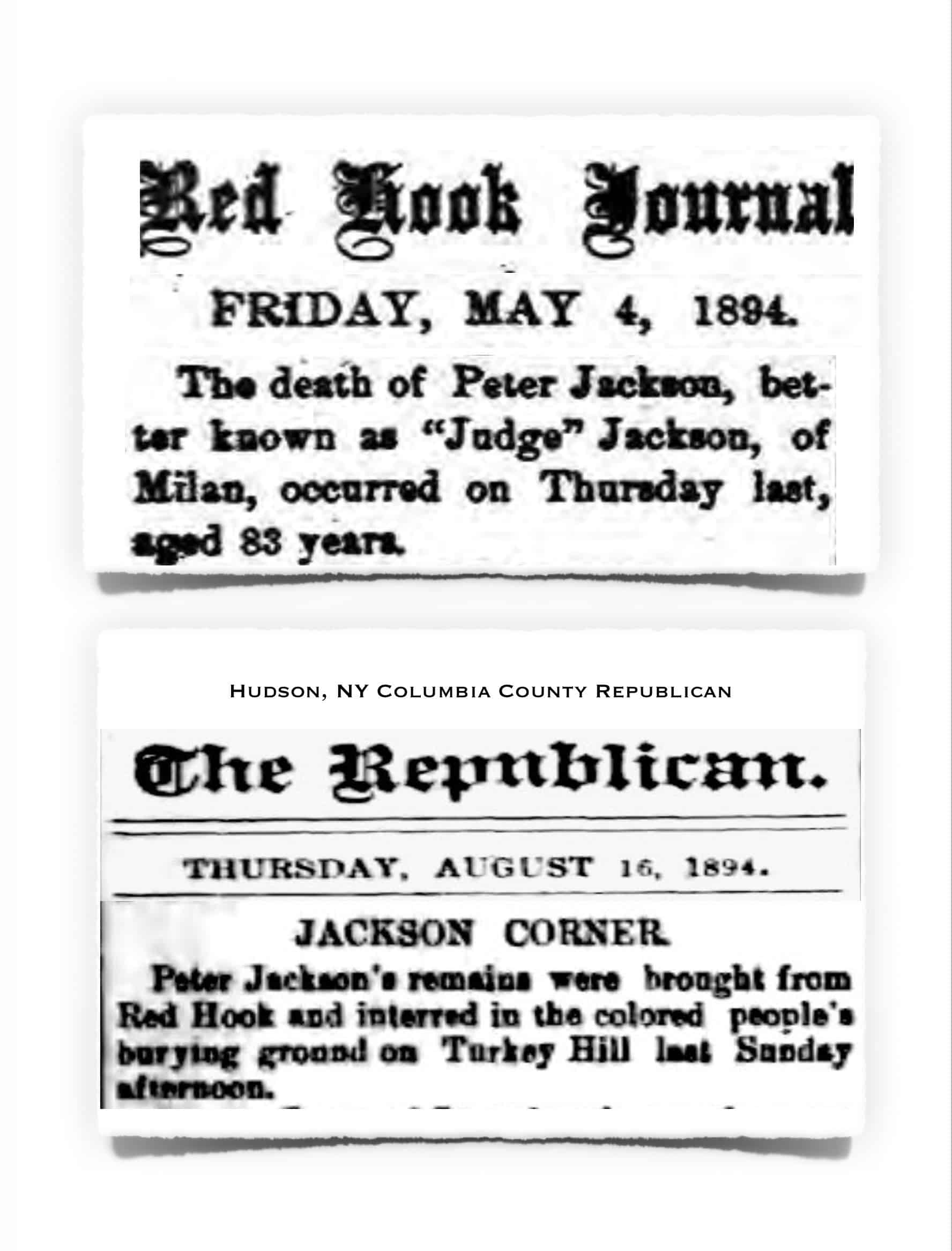

The highly regarded Milan author and historian, Burton Coon, wrote in the 1920s that the Jackson family emerged from being enslaved to the Martin family of Red Hook. He describes the home of one family member as a “hut,” and describes the “home” and family burial ground as being located on Milan’s Turkey Hill.

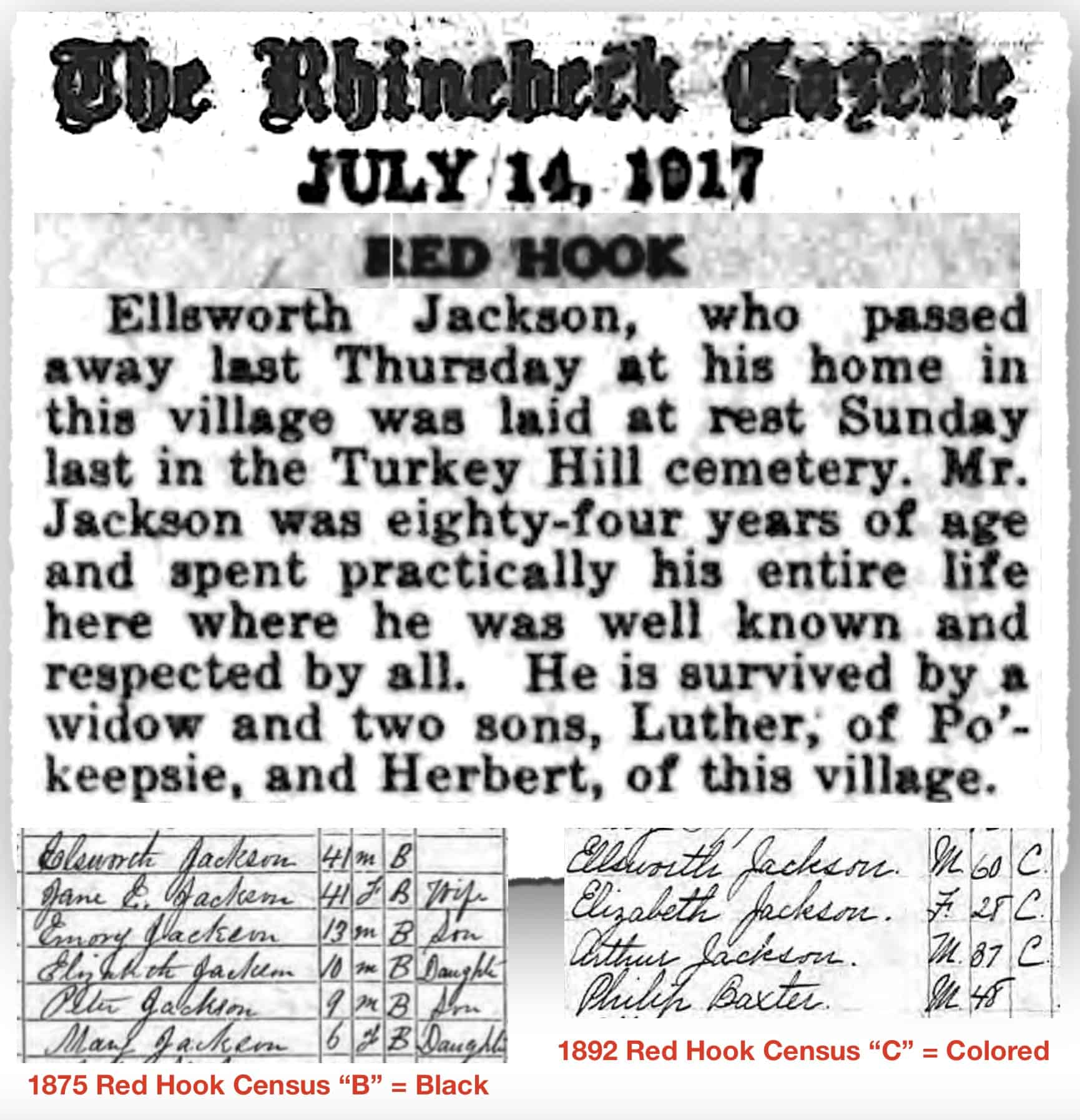

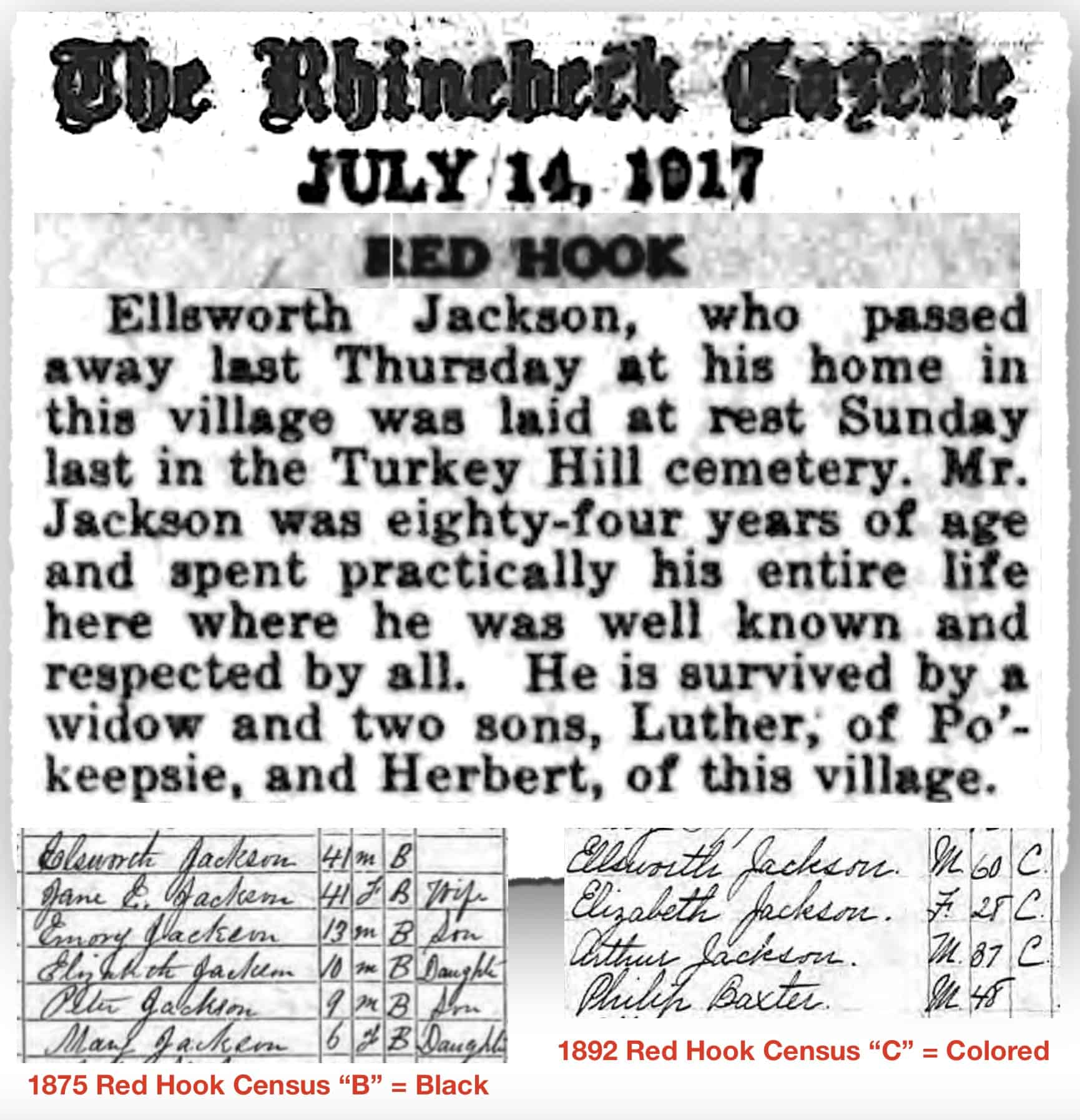

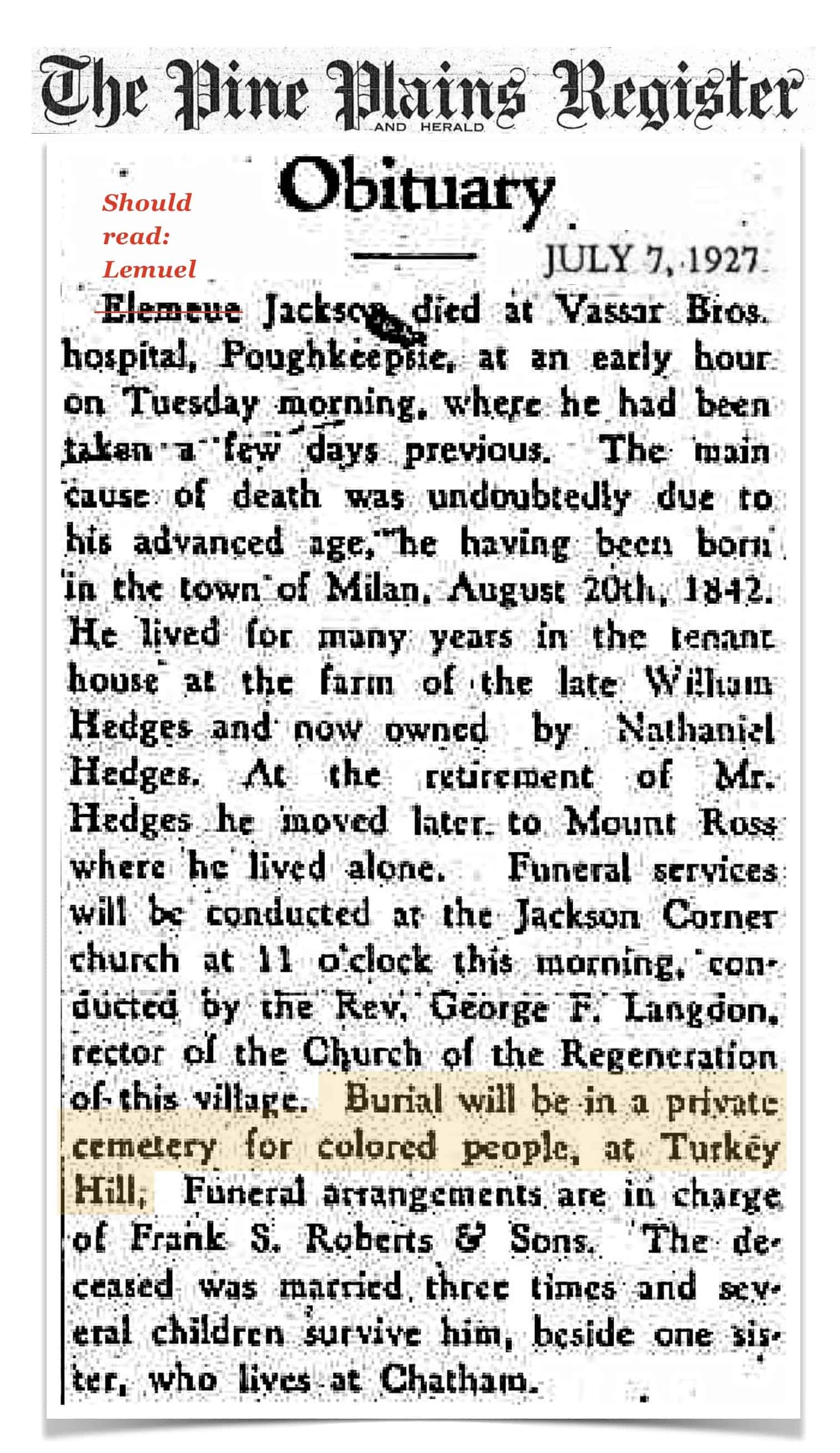

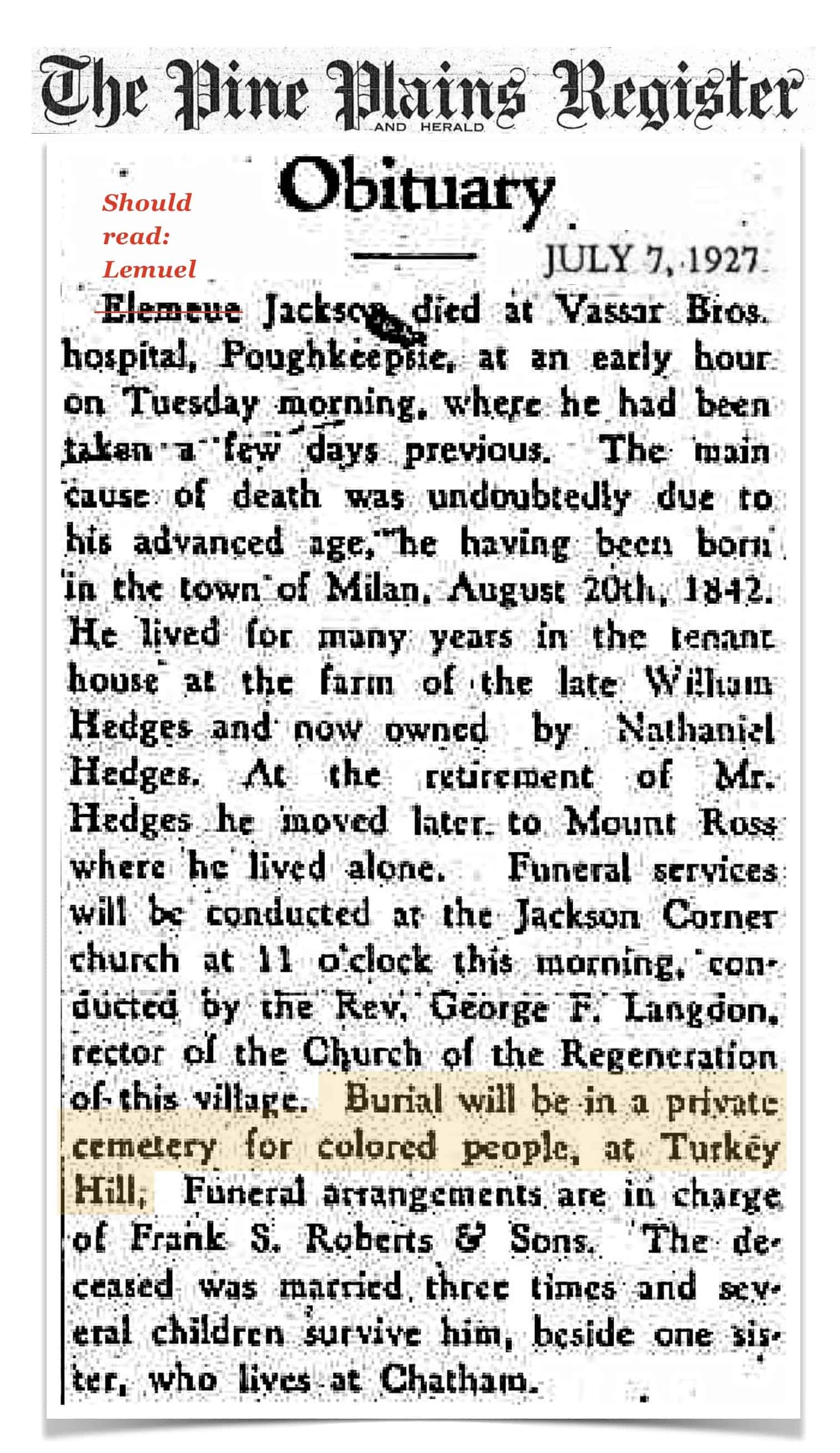

Three published obituaries of Black men, all Jackson family, Peter (1894), Ellsworth (1917), and Lemuel (1927) referred to them as buried at the “private cemetery for colored people” or “colored people’s burial ground on Turkey Hill.”

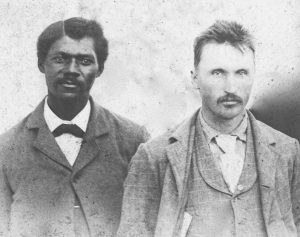

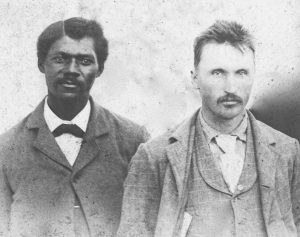

Milan’s Burton Coon, below right, had a regular newspaper column in the 1920s. In one column, below left, he wrote about a Black Jackson family of Turkey Hill, referring to their family burial ground. This would suggest that the burial of earliest owners, Jacob and Betsy Lyle, Nancy Bradford, were followed by burials of African Americans and mixed race individuals, especially the Jacksons, until at least 1927. Courtesy Burton & Emma Coon family, Bonnie Jing.

Milan’s Burton Coon, shown above with his home, “Trails End.”

Rhinebeck Cemetery Section E: Andrew Frazier family

Milan’s Andrew Frazier, a Black Revolutionary War veteran who did receive a Federal pension, was buried at home on his Milan farm until the family sold the land in the early 20th century. The remains were relocated to a family plot adjacent to, but technically not in, Section E, the section designated for Persons of Color, and paupers. Right: From left clockwise, the headstone of Andrew Frazier who died in 1848, and headstones of descendants who fought in the Civil War, in World War I and World War II. Andrew Frazier’s great-granddaughter, Susan Elizabeth Frazier, was the head of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th Infantry in WWI.

Right: Susie B. Frazier, right, with Burton Coon’s wife, Emma. Susie was the last of the original Black family settlers members to die, in 1952. She is buried at the family plot in Rhinebeck. Courtesy Burton & Emma Coon family, Bonnie Jing.

Southeast Section Yeoman’s Cemetery: Henry & Alma Jackson family

Left: In top photo, WWII veteran Walter Patrice visits the southeast section of Milan’s Yeoman’s Cemetery in 2018, fulfilling a lifelong ambition he shared with his mother to locate the resting place of his great-grandparents and his grandfather’s siblings including Ferris Jackson, shown in photo below with Burton Coon.