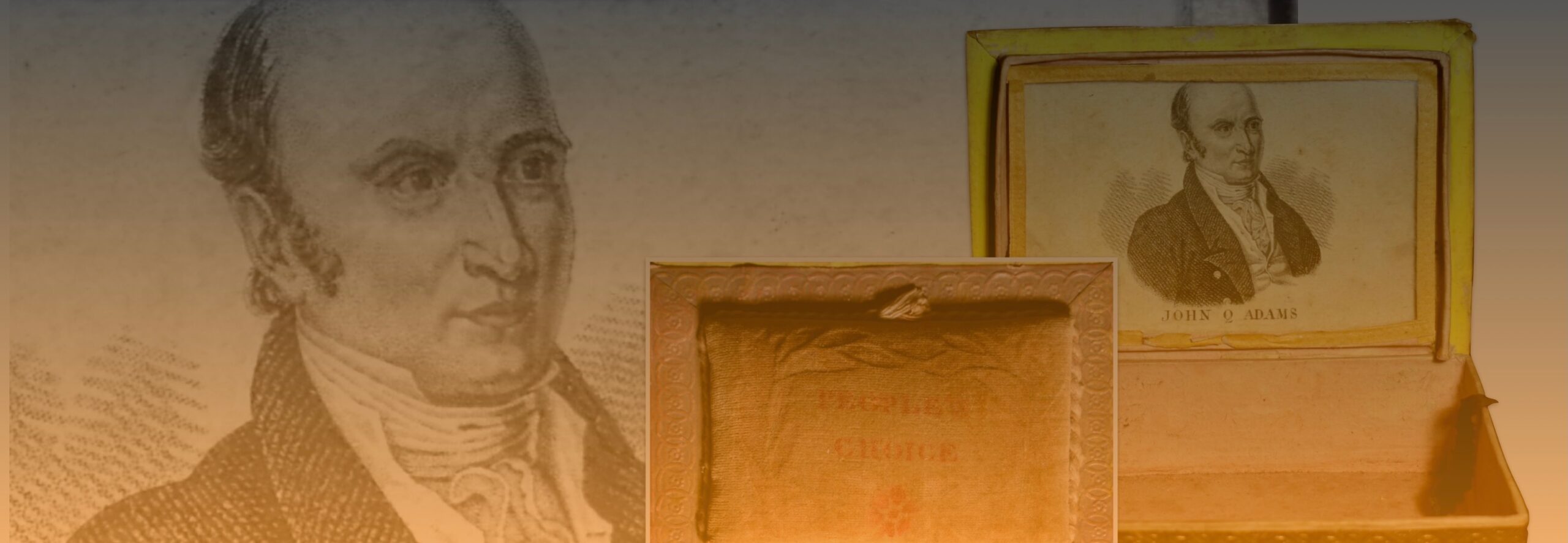

A small sewing box in DCHS Collections says “The People’s Choice” on the top with an engraving of John Quincy Adams on the inside. It is an early example of a political campaign trinket. Adams was elected President in 1824.

Whether he was the people’s choice, or not, is debated among historians and scholars and shows how the American electoral system has been evolving over time. The election outcome is often referred to as having been a “corrupt bargain” which is language that showed up in local newspapers at the time.

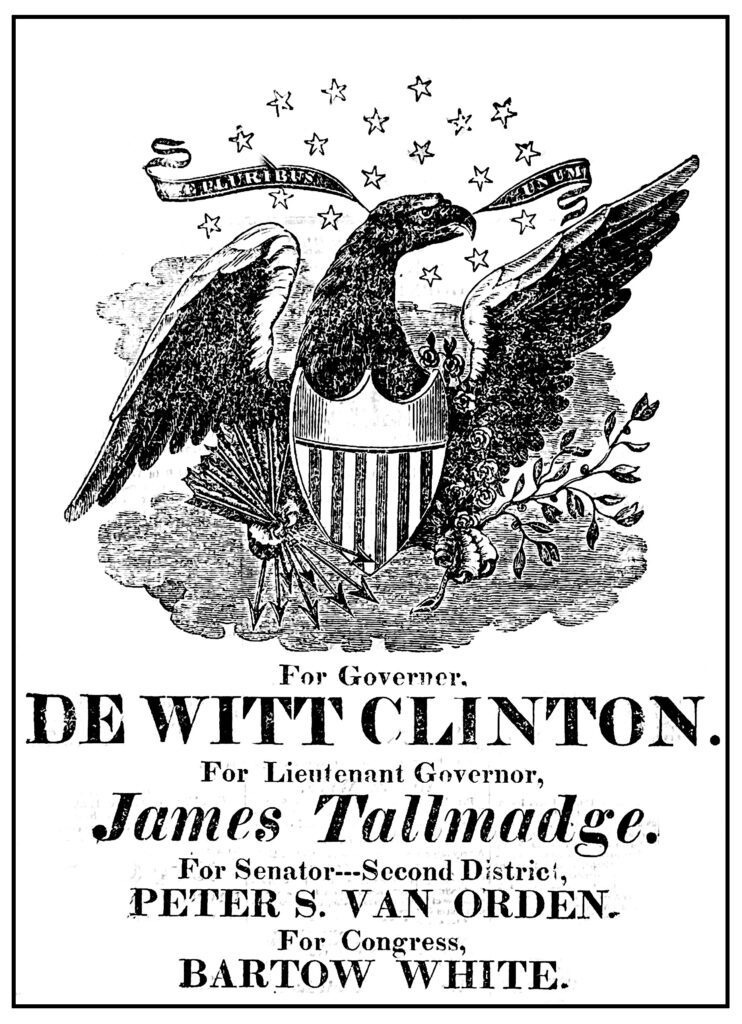

The election was conducted from Tuesday, October 26 to Thursday, December 2, 1824 and involved four major candidates: John Quincy Adams, mentioned earlier, the son of the second US President, was from a well-to-do and established Boston family. Andrew Jackson, the rough and rugged self-made military man was from Tennessee. Also running was House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky, and Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford of Georgia. Town of Amenia’s Smith Thompson, then Secretary of the Navy, had wanted to run but pulled out from the crowded field.

First, let’s look earlier that year when bills that would have changed the system in New York from having electoral college electors chosen by a vote of a joint session of the New York State Senate and Assembly, to direct election by voters going to the polls as they are today. This “direct” system was in place in most States, but not New York State. The change in law failed. The Poughkeepsie Journal was furious, editorializing on March 3, 1824, “Voice of the People. The proceedings of the people who are daily assembling in the different towns and counties of the state to express their wishes respecting the electoral law and their indignation at the conduct of Governor Yates, [US President] Martin Van Buren and the other men who have lent their influence and exertions to defeat the public will on this occasion pour in upon us in such floods that it is no longer in our power even to notice all of them…”

So in late October the two bodies, the NYS Senate and Assembly, got together to vote.

Several rounds of voting were inconclusive because both houses needed to agree on a candidate. Ultimately, John Quincy Adams got a majority of votes in both houses, including the support of Dutchess County State Senator Isaac Sutherland, of Stanford. New York’s 36 electoral college votes were sent to the US Capitol in Washington DC, for John Quincy Adams.

But when all twenty-four states’ votes were counted, four candidates split the vote such that none won enough electoral college votes to become President. In States where votes had been counted, Jackson had a majority of the popular vote: Jackson got 151,363 and Adams 113,142. Jackson got 99 electoral votes and Adams got 84; but 131 was required to win.

The rule that was in place then, is the rule that is in place now. When a candidate does not receive enough votes from the electoral college, the Presidential election is determined by one vote from each state in the US House of Representatives. Each state’s vote is determined by a majority of votes of the congressmen for that state. New York had 36 Congressmen.

During this unprecedented period newspaper editorials lobbied for their respective favorite candidates. The Poughkeepsie Journal was firmly for Andrew Jackson, writing, “…Jackson could probably poll twice as many votes in old Dutchess as all of them together.” The local names associated with the promotion of Jackson for President were formidable: Hyde Park’s Morgan Lewis, the former Governor, among them.

The Journal editorialized repeatedly that the public should lobby the local Congressman at the time, William W. Van Wyck of Fishkill, to vote for Jackson, although his vote would be but one of 36. The majority vote of the New York delegation went for John Quincy Adams. In what became known as the corrupt bargain, Clay lent his support (and all his electoral college votes) to Adams with the agreement that Clay would become Secretary of State (which he did). This gave Adams enough votes to win in the House of Representatives.

On February 2, 1825, the Poughkeepsie Journal reported the following, “The latest rumors from Washington represent that Mr. Adams and Mr. Clay have concluded a bargain by which the latter has agreed to smother his resentment against the former and unite in making him president. rumor says Mr. Clay is to receive as payment the office of Secretary of the State. Such are the rumors from Washington that efforts are being made to defraud the American people of the candidate of their choice by corrupt combinations among some of the leading friends of Adams and Clay.”

Two weeks later the Poughkeepsie Journal editorialized with an olive branch, “Having been decidedly opposed to Mr. Adams election to the presidency from a sincere conviction that he was unworthy to fill that exalted station it will not be expected that we should rejoice at his success especially when we add as our firm belief that Mr. Adams is not the choice of the nation and that his election has been affected by bargaining and corruption. Still, Mr Adams has been chosen agreeably to the forms prescribed by the Constitution and we must submit to his reign with the best grace we can.”

Four years later, in 1828, Adams and Jackson met in a rematch. Jackson took 56% of the popular vote and won almost every state outside of New England. Jackson handily won Dutchess County and all towns went for him except the following for Adams: Beekman, Hyde Park, Pawling, Union Vale. The “people’s choice” of 1828 emerged as Andrew Jackson.