Hyde Park’s New Guinea community was a transient, two-to-three generation community of color in the period just before, during, and after the U.S. Civil War.

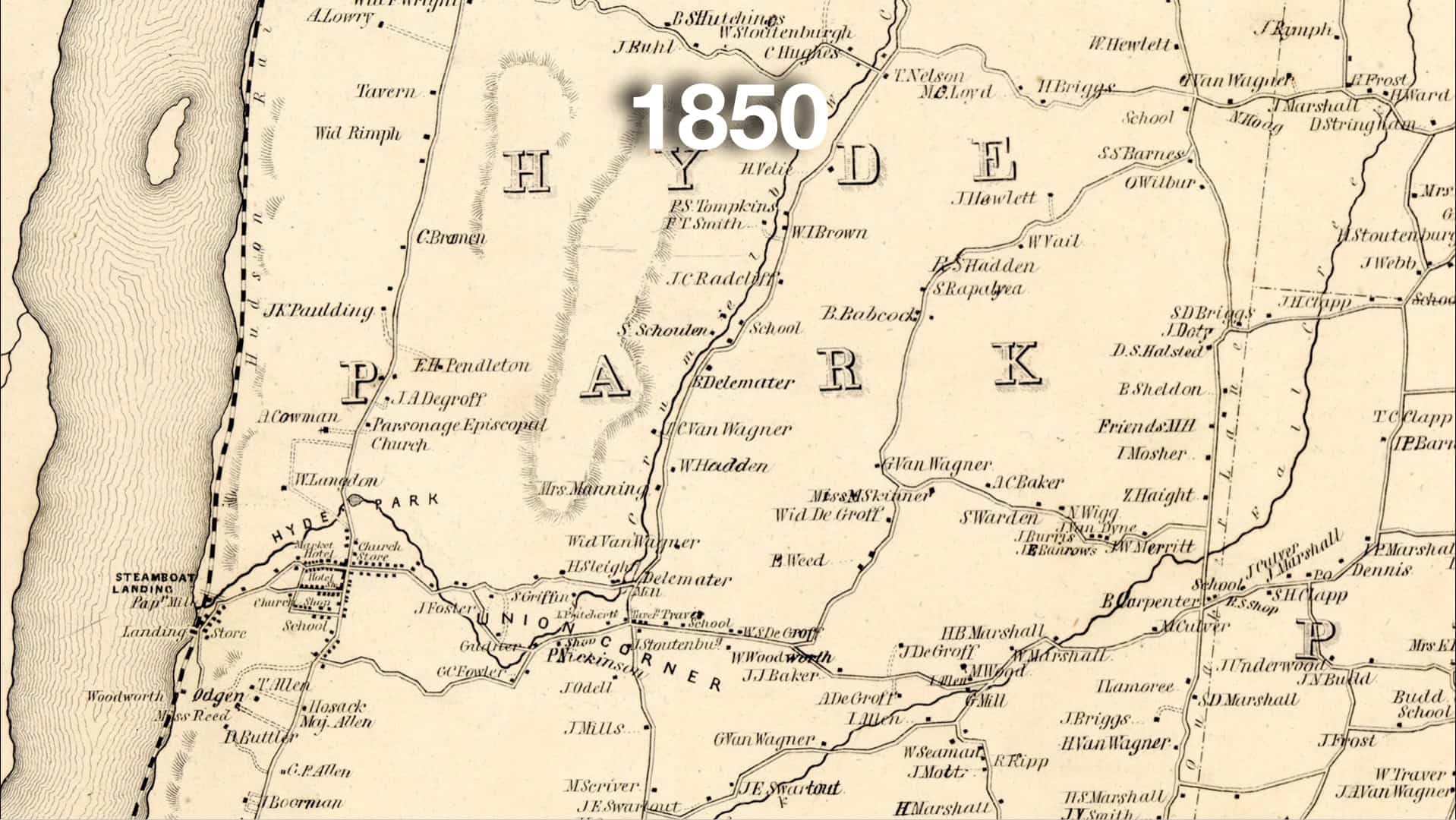

The first Federal Census in 1790 shows that 80% of Dutchess County’s population of 2,200 persons of color were enslaved. About two-thirds lived along the Hudson River, and one-third lived in inland rural parts.

After the 1827 abolition of slavery in New York State, New Guinea became home to formerly enslaved persons from around the area who banded together, in part, to provide safety during this period of transition.

The continued enslavement of four million men, women and children in the U.S. South created a risk of kidnapping for local free persons of color.

The passing of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law intensified the divisions in the country. New Guinea became a permanent home to self-emancipated freedom seekers on the so-called underground railroad from as far away as Virginia and Brazil, as well as a temporary stop on the way to Canada.

The searing bright spark emerged from both the heat of confrontation, and the light of reason, education, and access to property and business ownership that illuminated a way forward.

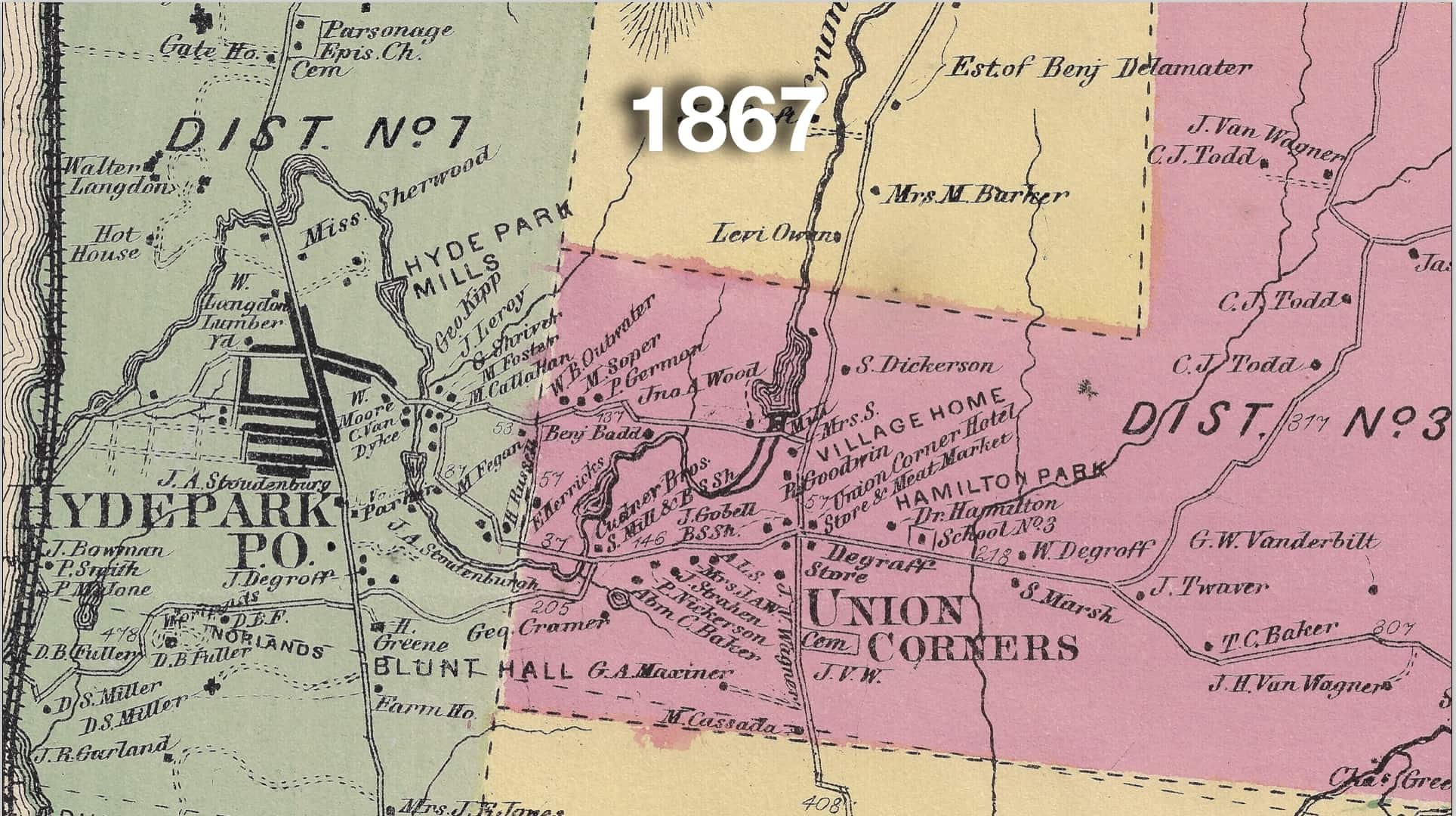

The passionate countervailing national arguments literally abutted the New Guinea community. Adjacent to the west were those who enslaved others like three generations of the Bard family, and those, like James K. Paulding, who became published national voices arguing for the permanent institution of slavery.

Adjacent to the east was the outspoken and activist abolitionist Quaker community. The Crum Elbow Meeting House, which stands today with its ancient cemetery, was home to (and today is the resting place of) the leading national abolitionist voices of the DeGarmo family, including Elizabeth, “Lizzie” DeGarmo.

Revealing the frequent seeming contradictions and subtleties of the issue, while some of the founders of Hyde Park’s St. James Church were slave owners, the church operated as an open community. Persons of color were invited to worship and attend Sunday school. The church offered paid employment. The St. James cemetery policy was unusual at the time in that it allowed the integrated burial of all races.

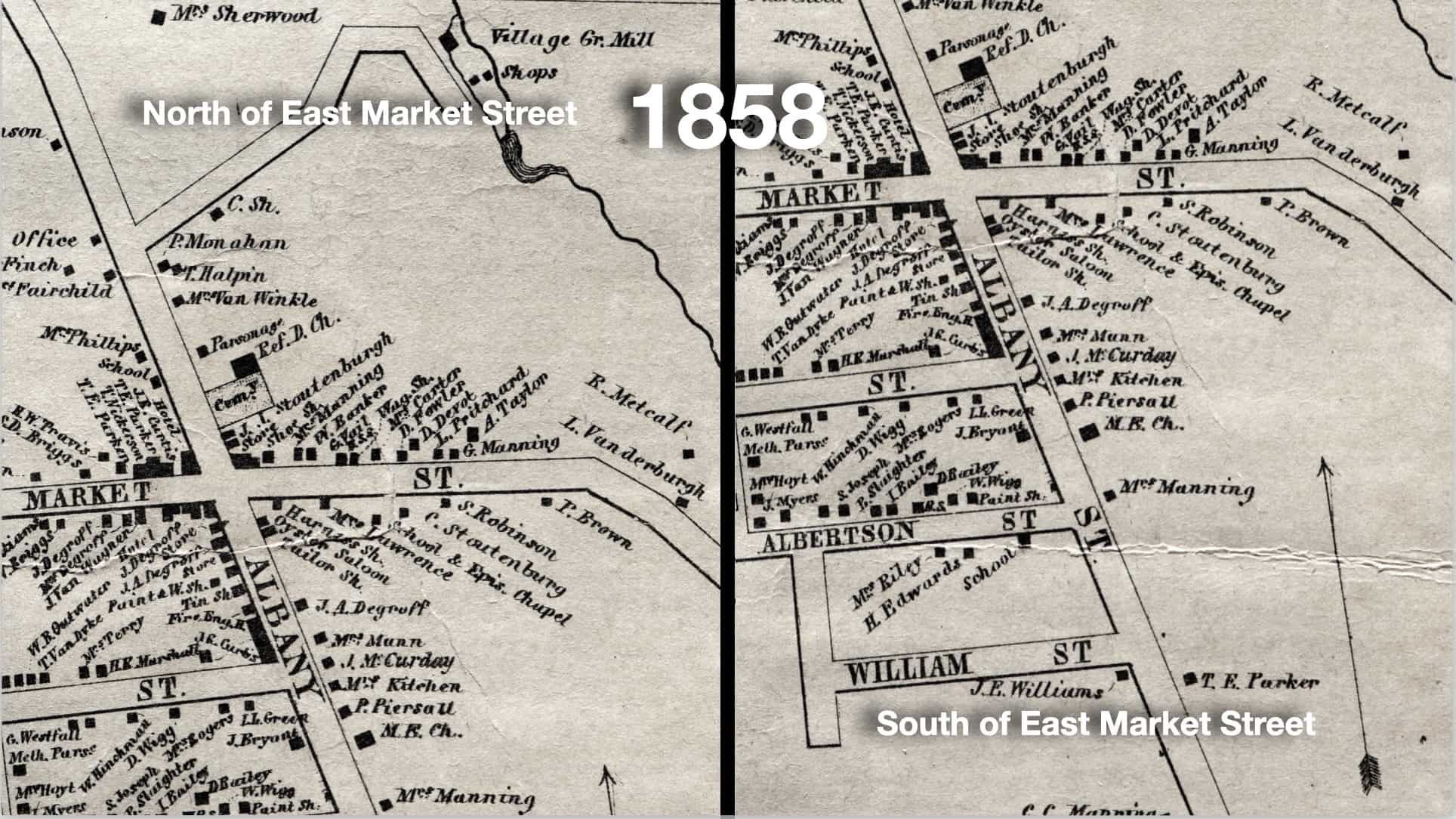

The bright spark was searing. There was destitution, disease and death, among a community that grew by a factor of five between 1810 and 1830. Many lived in unhealthful conditions in shanties and lean-tos along the Crum Elbow Creek. At the same time, persons of color became successful property and business owners, and began to define individual paths in the pursuit of their personal happiness. In many instances those paths took them away from Hyde Park, and in some instances it did not.

We are fortunate to be able to draw from insights from a 21st century archaeological investigation, the 20th century local historian Henry Hackett, the 19th century local historian, Edward Braman, and the resources of the Dutchess County Historical Society. ~ Bill Jeffway

Watch the video:

50-minutes. For new window & full view click on Watch on Youtube.

To view within the above window, click red play button.

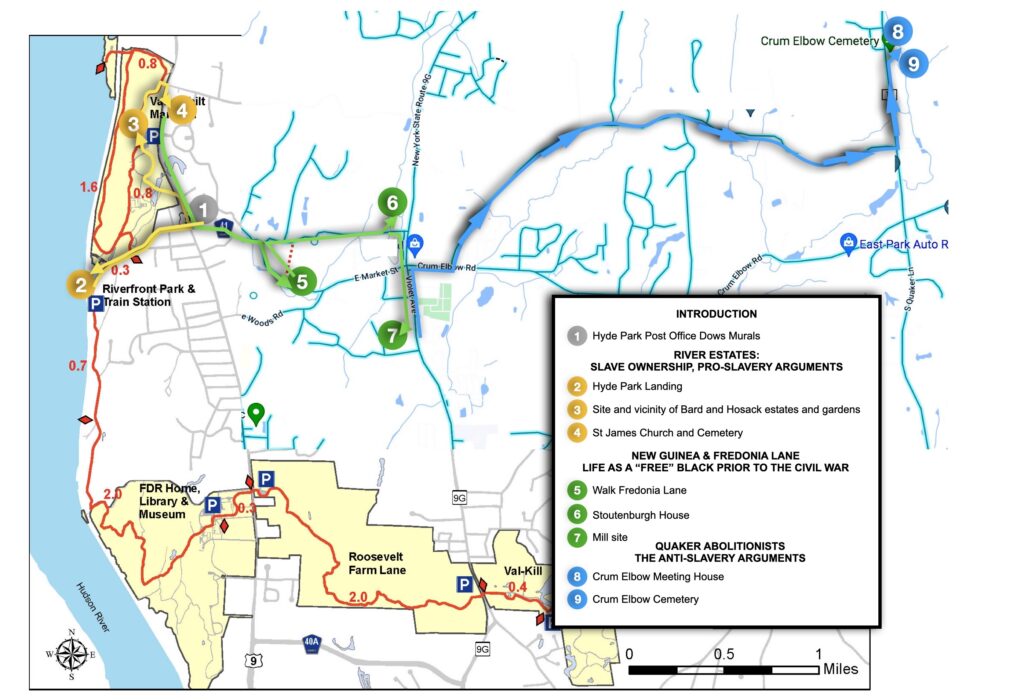

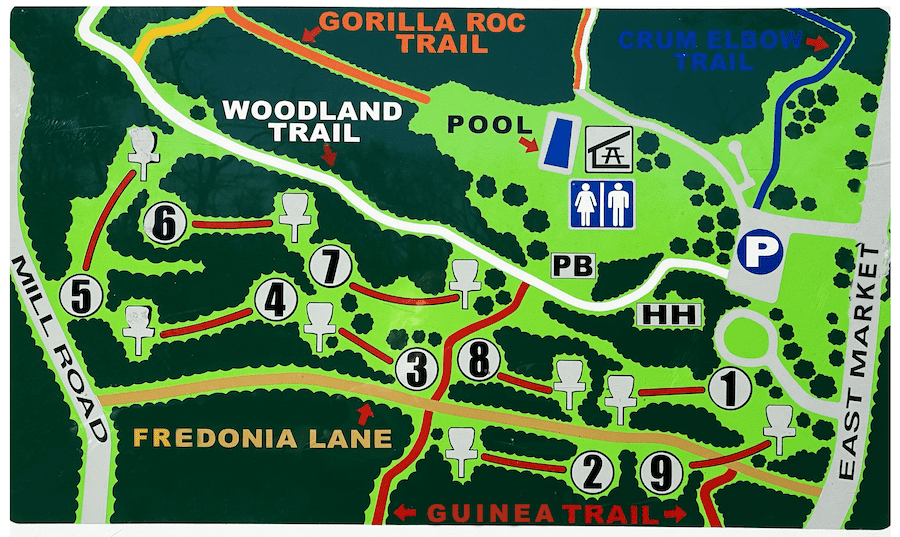

Take the trail:

Put cursor over window to scroll down through the story and map.

There are 29 “stops” in Chapter One, and 9 “stops” in Chapter Two.

End of embedded trail window.

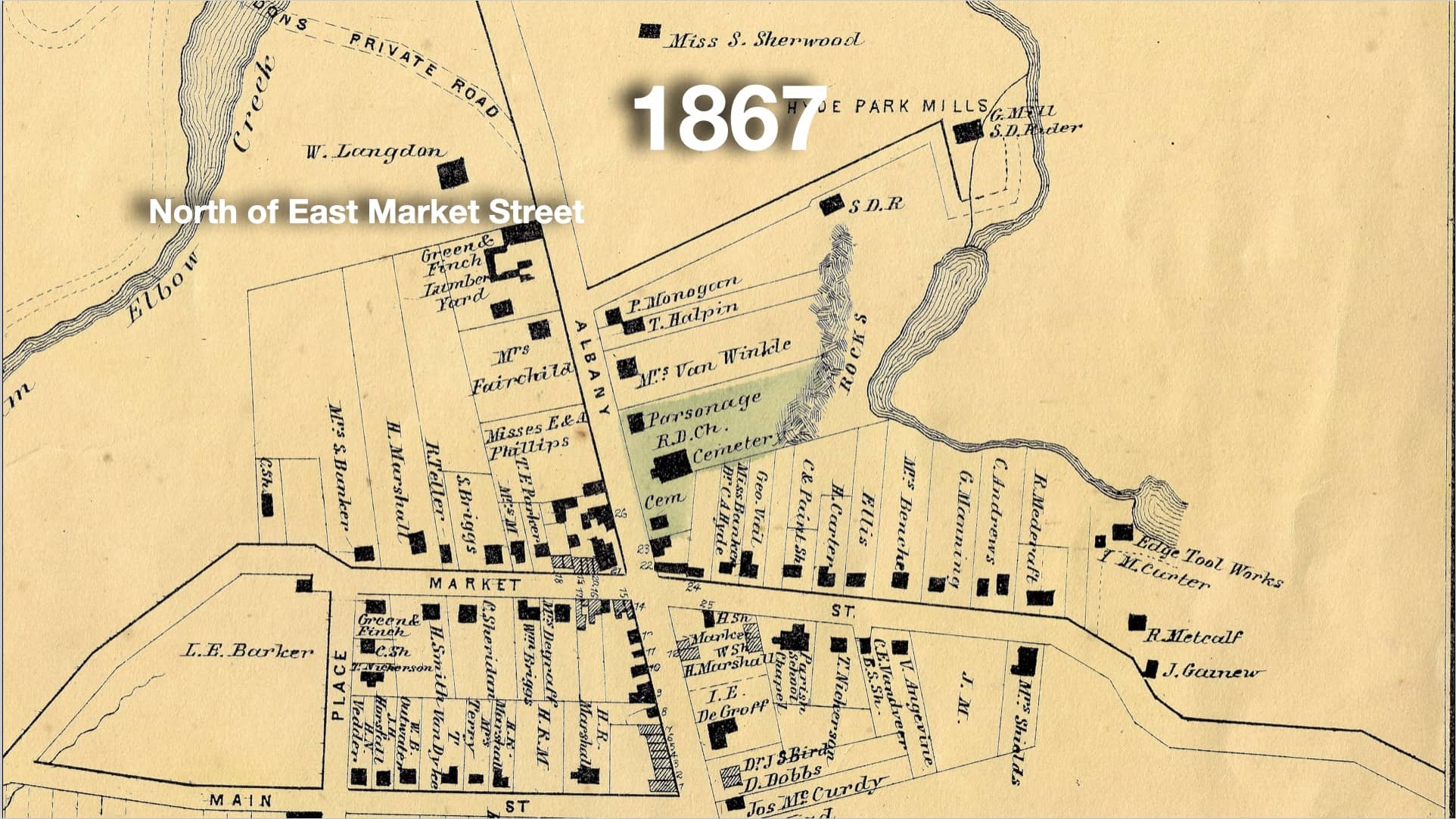

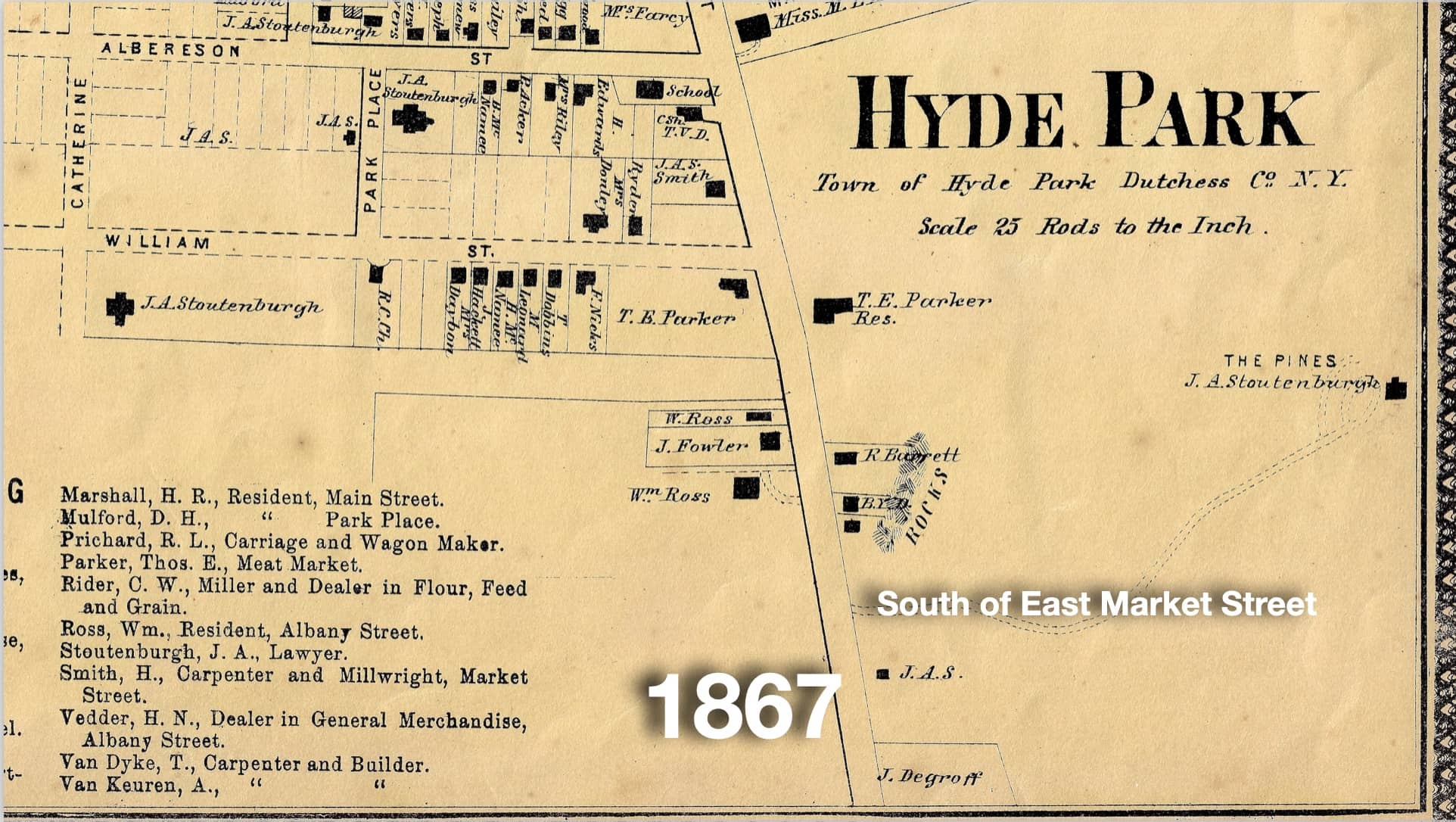

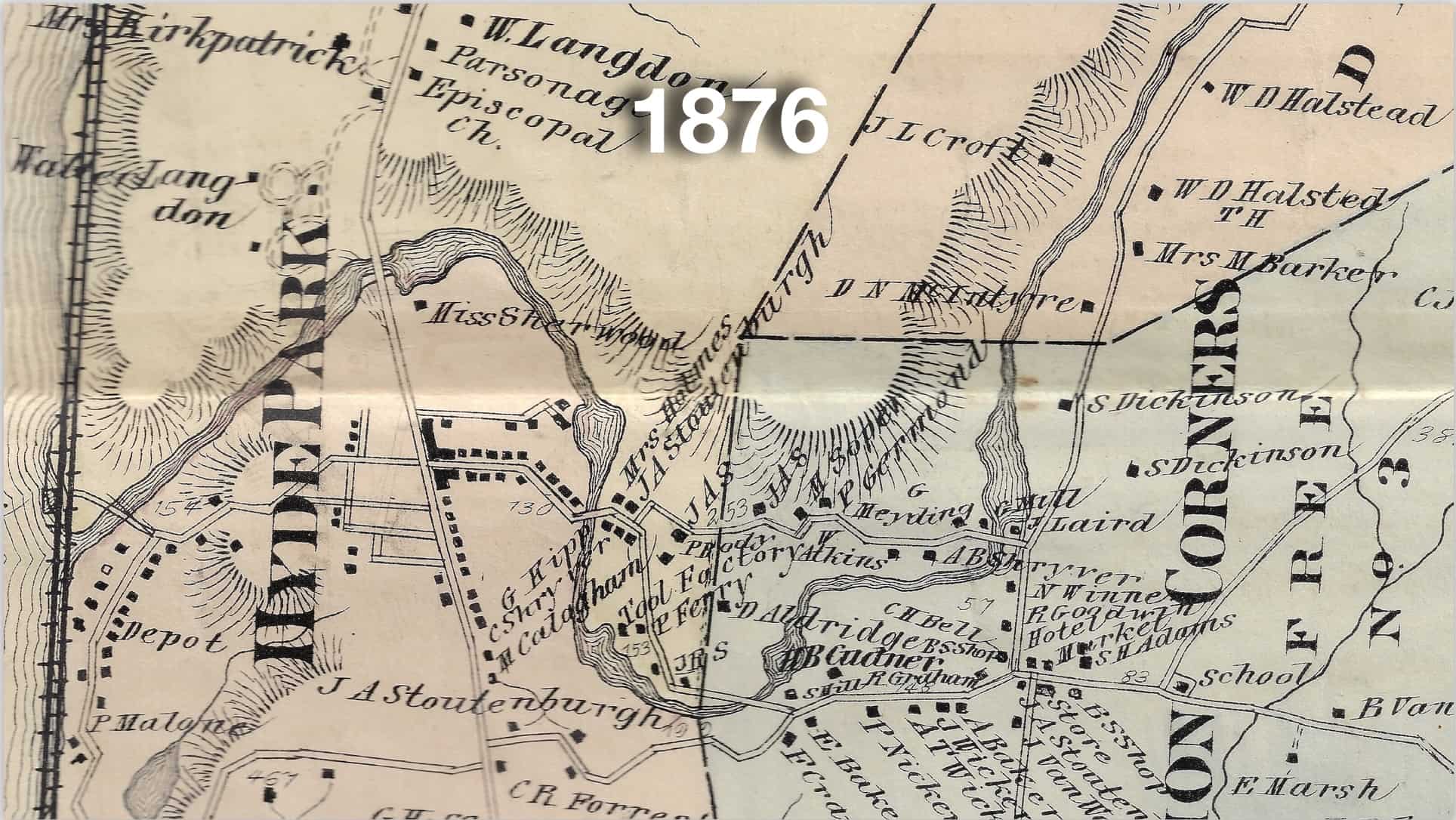

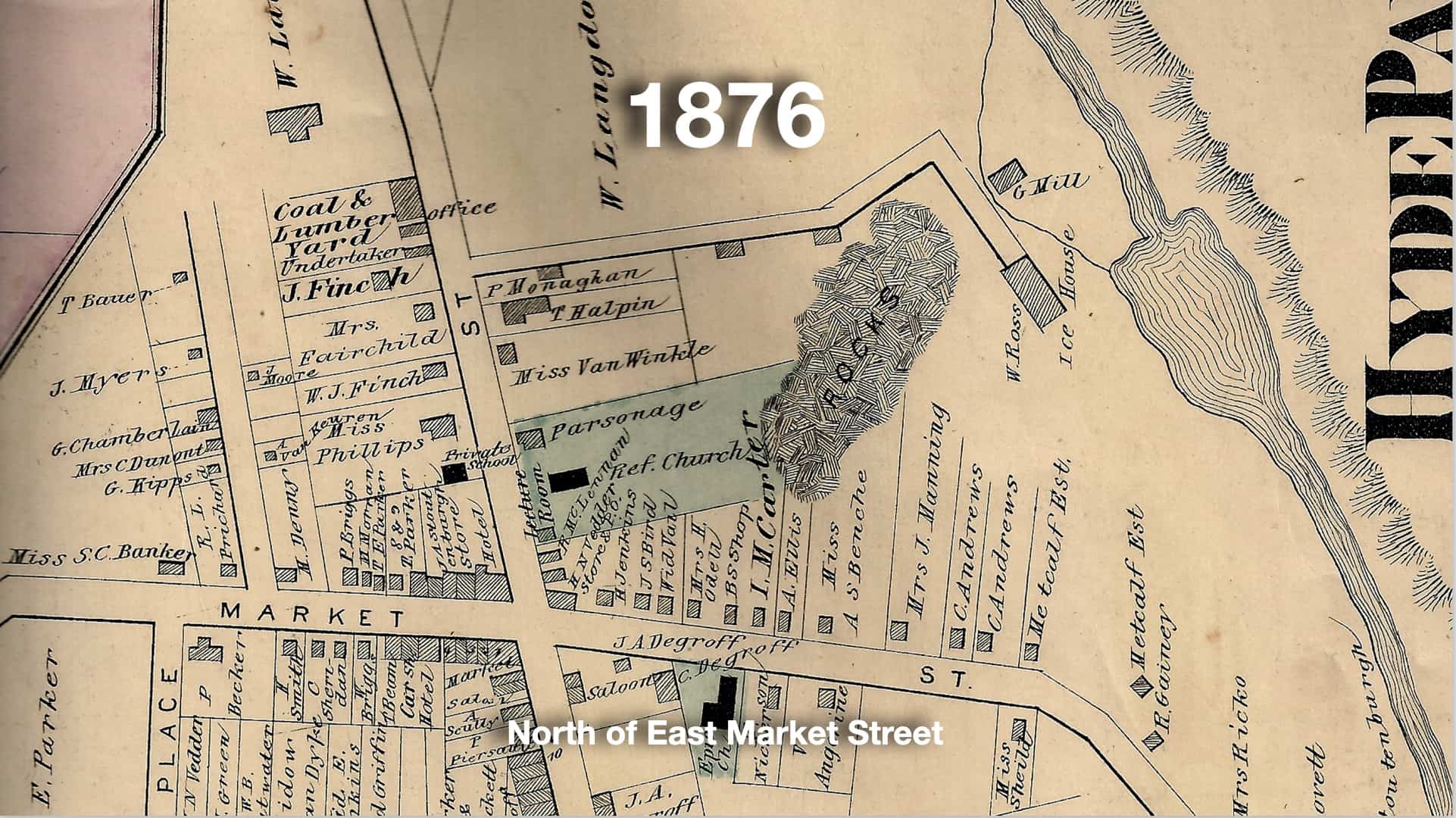

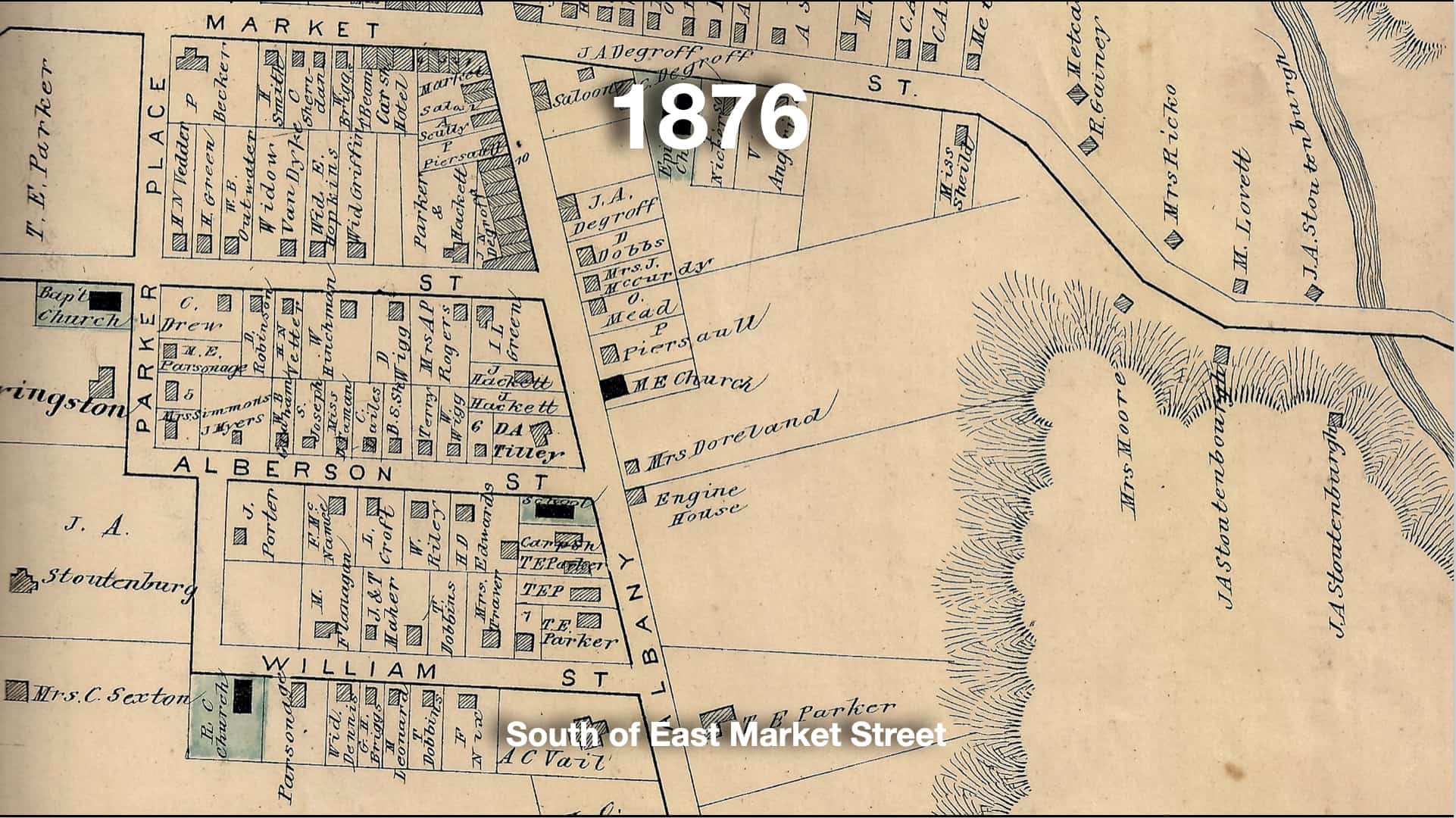

Maps:

Photos:

Above: We have enjoyed introducing Columbia University students and NYS Parks summer students to the site.

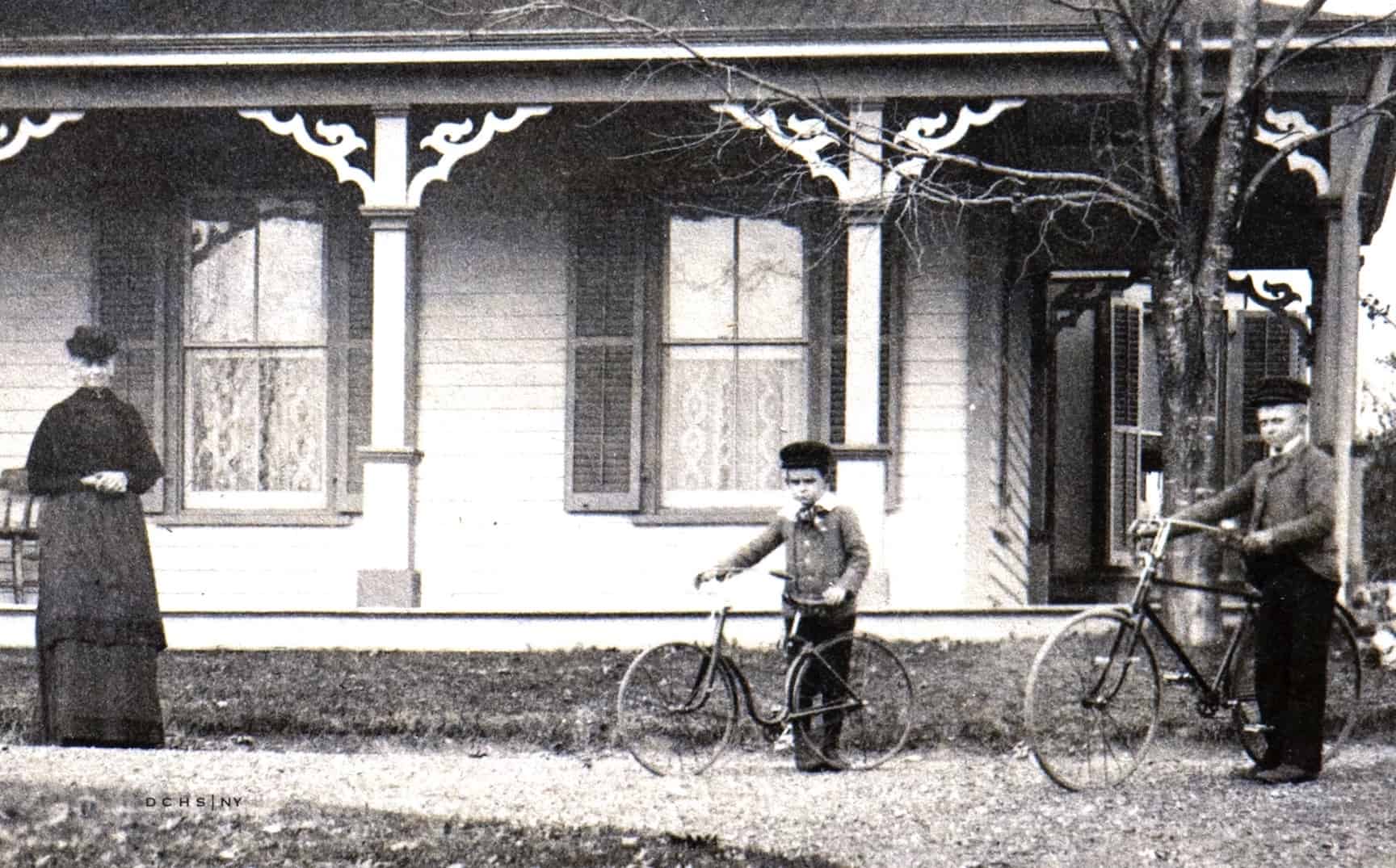

Family photos of Henry Hackett and his family and home, and a contemporary map.