This article is part of a year-long program recognizing the 100th anniversary of national women’s suffrage, other articles here:

This article is published in the March 25 Northern/Southern Dutchess News / Beacon Free Press and is shared here courtesy of the publisher and DCHS. By Bill Jeffway.

Fred Rogers, host of the children’s show “Mister Rogers Neighborhood†from 1968 to 2001, was quoting his mother’s reassuring advice in difficult times. Those words seem very relevant today. Let’s focus on women helpers, given it is Women’s History Month.

Just over a century ago, as many women were advocating for their right to vote (and some were advocating against it), women emerged as vital “helpers†in the front line of two life and death battles. The first battle was the “World War,†especially during US involvement April 1917 to November 11, 1918. The second was the global flu pandemic. Peaking in September and October of 1918, the “flu†rapidly declined the same month the fighting stopped, in November 1918. Two great battles were, or were close to, being under control at once.

The fight for suffrage formally started in 1848, but the culminating ramp-up to success arguably began in 1910 with the formation of active, local suffrage groups. As the war grew in terrible scale in human lives lost, and men and women were wounded and maimed physically and emotionally, and many of the most basic needs like food, water, electricity and coal were in short supply, women stepped up in very visible and profound roles. Many historians argue that the visibility of this vital work made all the difference when in November of 1917, a referendum in New York State on women’s suffrage was a success. The same question had been defeated two years earlier in November of 1915.

Effective 1918, women in New York State could vote in any election from town elections to the election of the President of the United States. Women across the entire US would be granted the right to vote two years later, in August of 1920 with a Federal Constitutional Amendment affecting all states. The centennial approaches.

World at War: Local Women Give Their Lives

But even armed with the power of the ballot, no one could have imagined the scale of what was to come in 1918. Relative to the war, women emerged in vital roles from stepping into farming, to more traditional roles as nursing. All “strata†of society were engaged.

In April of 1918, word was received that Mrs. Edward H. Landon and two daughters were killed when a Paris Church was shelled by German long range guns. The Landons had an estate in Staatsburg. Mrs. Landon was the niece of Rhinebeck’s Levi Morton, who was Vice President of the United States 1889 to 1893. They had been serving as nurses through the Red Cross, which was headed up in France by another Staatsburg woman, Ruth Morgan. Morgan was a good example of a woman arguing for suffrage who put very visible work, including moving to France, into the war effort.

Suffragists deflected calls to abandon their advocacy of suffrage to focus fully on war efforts, arguing in a way that would prove to be true, that they wanted the vote not as a matter of principle, but as a tool to create positive social change through tireless work. They argued successfully that they needed to do both.

Another example of this is Poughkeepsie’s Nina McCulloch Mattern. She was featured in a nation-wide training film showing women how to “can†food for winter storage (using glass jars). The banner on her car reads, “Suffrage War Service.†The fact that a successful and visible suffragist could become a successful and visible war “helper,†was exactly the point suffragists wanted to make. But there was another battle looming.

In May of 1918, when the Poughkeepsie newspaper reported that Alfonso, the King of Spain was sick with a “mystery virus sweeping Spain,†it was on page 4, halfway down the page, in a small article. The fact that the disease was active and appearing in the US, and elsewhere in the world was not reported by any press due to war censorship. But Spain was a neutral country and did not have this censorship. This is the reason that so many to this day refer to the pandemic incorrectly as the “Spanish†flu.

By September and October 1918 the scale of the pandemic could no longer be kept under wraps. Nina McCulloch Mattern added wading into serve as a nurse at the pandemic emergency treatment center at Masonic Temple on Cannon Street to all her other work.

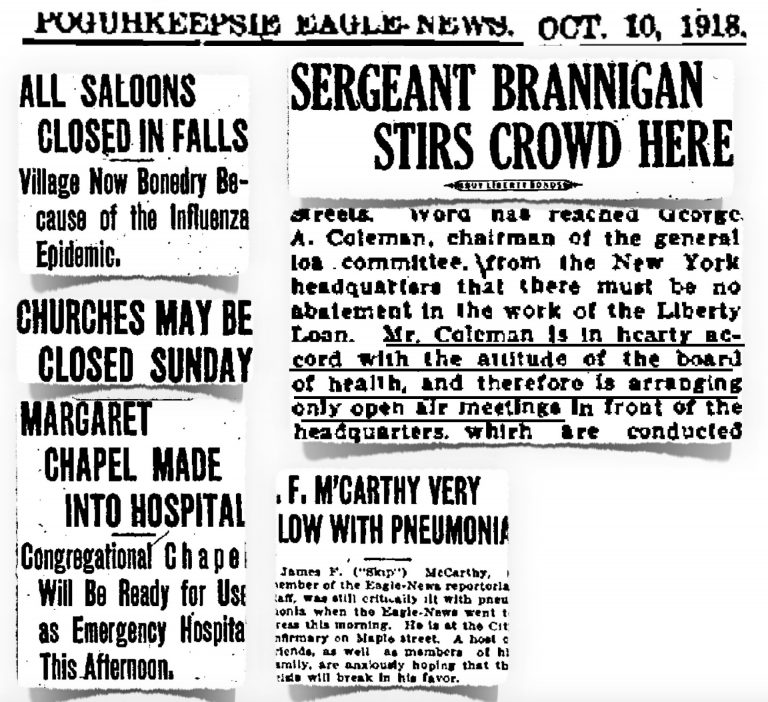

Conditions for a pandemic could not be worse. Great clusters of men and women were assembled tightly in training camps, on battlefields, on ships crossing the ocean. Add to this a lack of understanding that found Churches and theaters closed in Dutchess County, but mass rallies for war bond still proceeding. In addition, that particular strain of flu was deadly among the young and healthy.

Felled By the Flu

Nina died in October 1918 from the flu, age 36. By contrast, the woman who inspired her, her maternal grandmother, the town of Clinton-born Opehlia Shadbolt Amigh lived close to a century. Amigh’s life focus was the cause of the safety and education of young girls. Amigh’s life was almost three times that of Nina.

So much fell to the women of 1918. Even then the question was raised: where are the monuments to the women of the World War? To this could be added the same question relative to the women of the flu pandemic. And the wars and emergencies since.

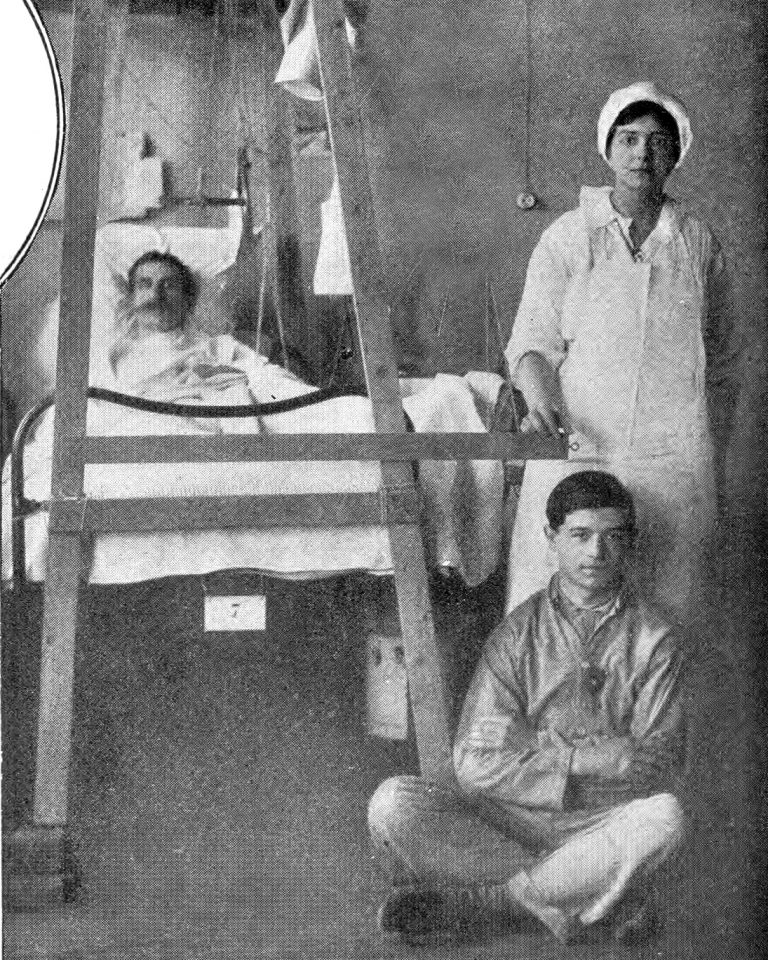

Above: Miss Lucy Landon, the great-niece of Rhinebeck’s Levi P. Morton, whose family estate was in Staatsburg, is shown at right in photo. The photo was published by the New York Times shortly before she, her sister, and her mother were killed outside of Paris during World War One by a long range gun while tending to the wounded. Courtesy New York Times.

Above: Poughkeepsie’s Nina McCulloch Mattern is shown in clips from a summer of 1917 nationwide training film on food storage. The banner on her car, “Suffrage War Service” makes the point that suffragists were not willing to give up the fight for the ballot while taking on essential war work. DCHS Digital Archives.Â

Above: On a single page of the October 10, 1918 Poughkeepsie Eagle News among headlines of closures of Churches, Saloons, illness of reporters, were stories of consecutive, nightly mass rallies for war bonds, the thinking being (incorrectly) that a crowd in open air is safe from transmission.

This article is part of a year-long program recognizing the 100th anniversary of national women’s suffrage, other articles here: