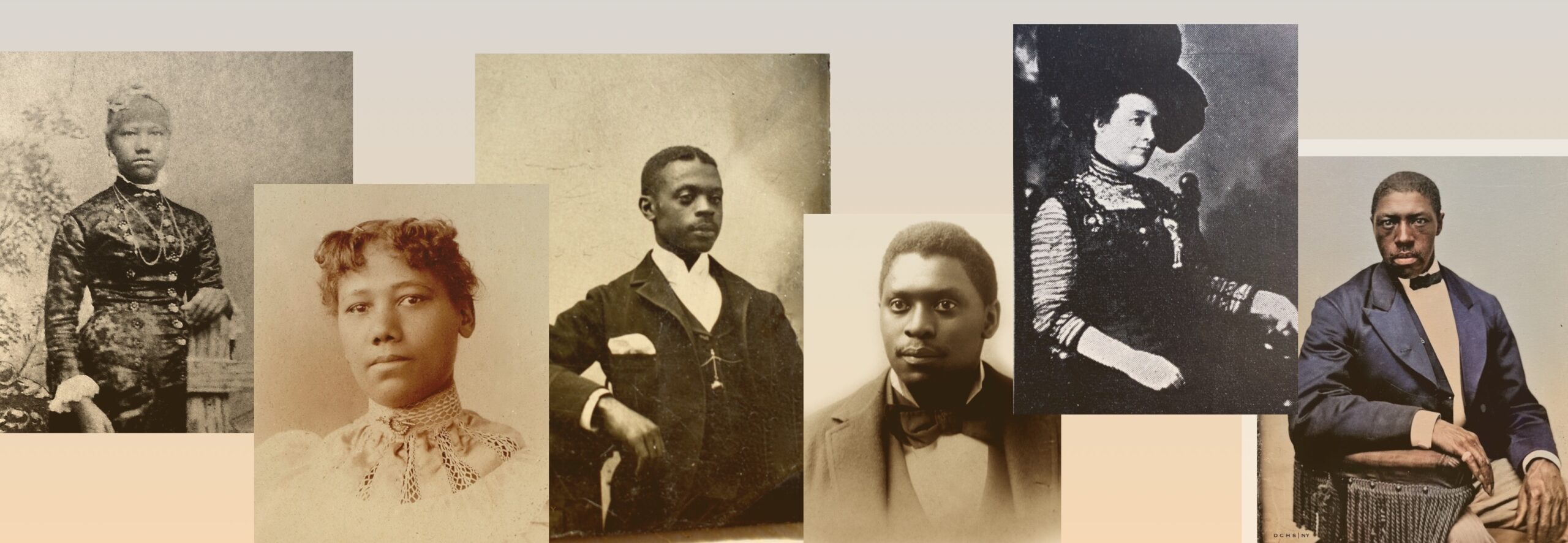

Inspired by HBO’s The Gilded Age. With one exception, all the photos above are from the DCHS Walter M. Patrice image collection, from the album of the family of Henry and Alma Jackson. The Jacksons bought 33 acres of farmland in the Town of Milan in 1865 and raised eleven children. The pictures give us a sense of the local Black community at the time. The image second from the right is Susan Elizabeth Frazier and is from Homespun Heroines by Hallie Brown, 1926.

Black Women Drove Change With Education, Words & Backbones of Steel

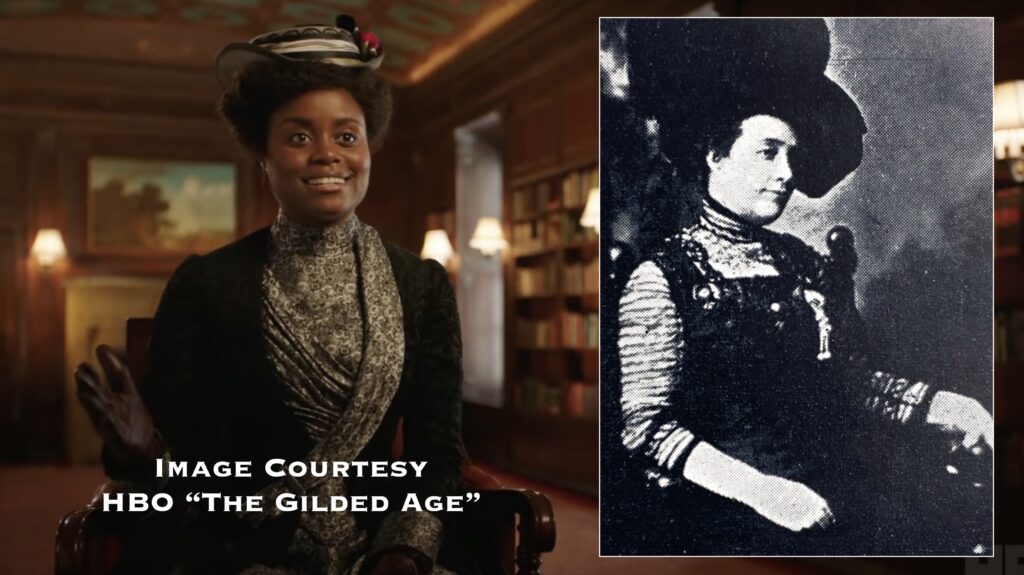

There was a debate within the Black community as to whether separate or integrated public education was preferable. The issue was depicted in the HBO series The Gilded Age and played out in real life in New York City with a woman with local ties who emerged as a national voice and icon. In both the fictional series, and the real-life Susan Elizabeth Frazier, values of competence, patience, courage, persistence and self discipline are evident.

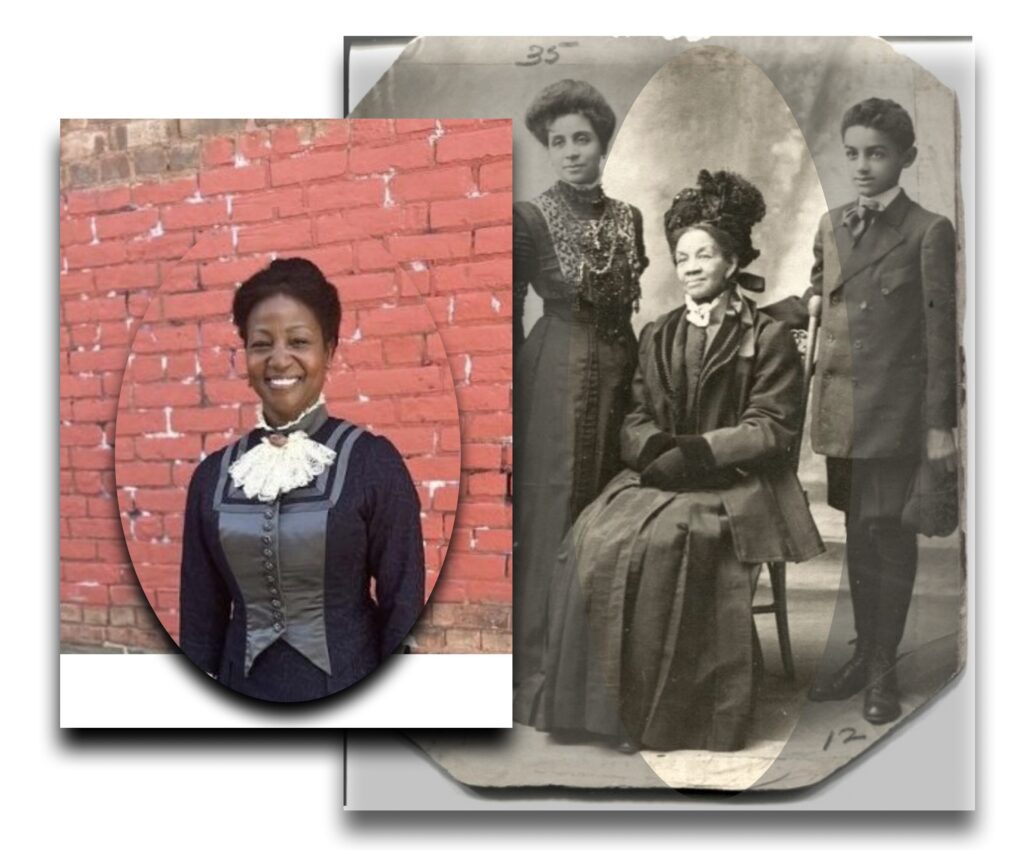

Above: The character Peggy Smith in the HBO series The Gilded Age is played by Denée Benton. The character’s focus on education, writing and publishing reminds us of the real-life Susan Elizabeth Frazier (1864-1924), the product of an 18th century Dutchess County family with living descendants today. Frazier’s great-grandfather, Andrew Frazier (ca. 1744-1846) was born enslaved, but was free after serving in the Revolutionary War out of northern Dutchess County.

By Bill Jeffway

Executive Director, Dutchess County Historical Society

This is a second article in a series inspired by HBO’s The Gilded Age. We recognize Black History month by looking at the themes and storyline of Black life portrayed in the two seasons of a program set in New York City between 1882 and 1883. We ask if there were real characters in our local history who were similar, or if some of the themes explored in the performance played out locally.

The leading Black character, Peggy Smith (played by Denée Benton) is a well-educated, skilled writer of fiction and political journalism who sought to create political and social change through her written words and persistent courageous actions.

One woman with local ties stands out in particular.

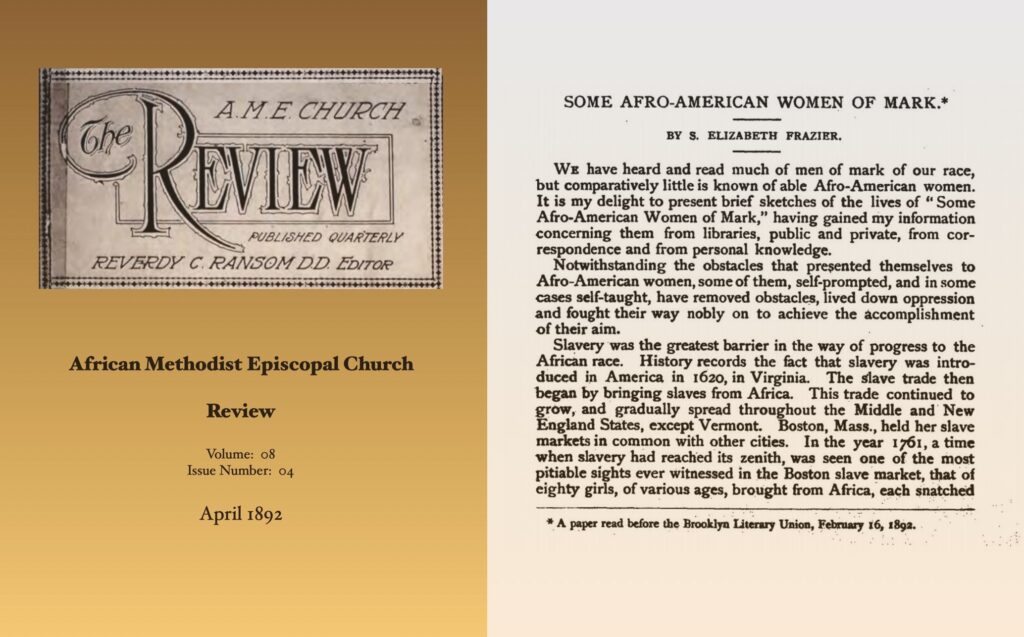

Susan Elizabeth Frazier (1864–1924) was similar in age to the fictional Smith and is buried in Rhinebeck cemetery in a four-generation family plot adjacent to the section created for persons of color. Frazier established herself with a February 16, 1892 talk at the Brooklyn Literary Union that was shortly after published in the national newspaper of the leading Black church, the quarterly AME Zion Review. In a talk titled, Some Afro-American Women of Mark, Frazier set a pattern she would repeat; speaking to the untapped capacity of both Blacks and women in society due to arbitrary limitations. In her talk, she profiled the many successful Black women who were under-represented in history and national consciousness such as the 18th century poet, Phyllis Wheatley, the sculptor Edmonia Lewis, and New York City schools’ first Black principal, Sarah Garnet who is profiled later.

Above: Susan Elizabeth Frazier in a photo ca. 1890 and another from 1919. A recent campaign to erect a memorial at the Frazier family plot at Rhinebeck cemetery at what had been her unmarked grave resulted in this headstone with the words, “Her voice endures.” DCHS image collections.

What we see in the fictional character of Smith and the real-life Frazier are Black women who early in their lives focused on their own education with a view to creating change through the words they penned and deployed in public. In addition to their skills and hard professional work, they courageously and persistently pushed aside barriers put in front of them due to their race or gender.

White Fifth Avenue & Black communities in Brooklyn

Frazier’s father, Lewis, like her grandfather and great-grandfather, was from the northern Dutchess County Town of Milan. He worked in New York City as a coachman for a wealthy, White Fifth Avenue family, just as the fictional Peggy Smith worked for a wealthy, White Fifth Avenue household.

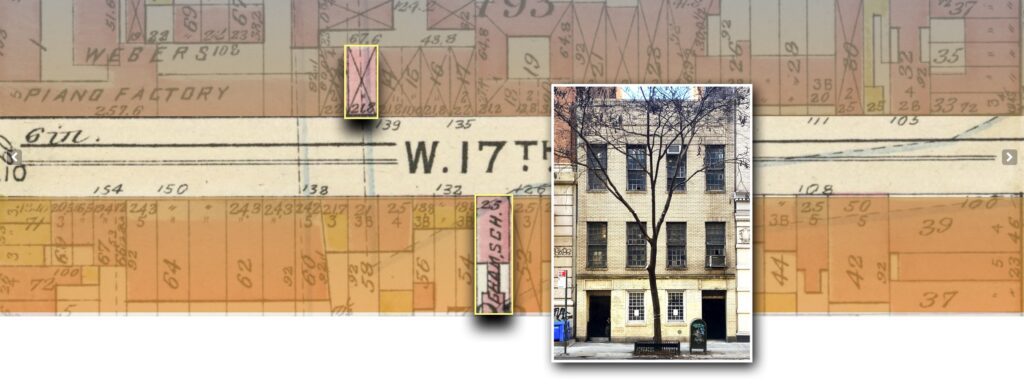

Susan Elizabeth Frazier was grew up on West 17th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues, closer to 7th Avenue. The street had many two-story horse stables, with second-story apartments housing many coachmen like her father, who were Black or Irish.

Almost exactly across the street she attended “Colored School No. 4.” This was fortuitous.

At school Frazier found a role model in the principal, Sarah J. S. Tompkins Garnet, who was the first Black woman to serve in such a role in New York City. The character of the real life Garnet is portrayed in The Gilded Age by Melanie Nicholls-King, who leads the effort to stop school closures in the fictional episode.

There is no doubt that the talented young Frazier would have absorbed both practical learning and profound values in her education with Garnet at the helm of that school.

Above: Frazier grew up with her parents and siblings in a second-story apartment above a horse stable on the north side of West 17th Street. The street accommodated many horse stables, and the families of coachmen above them. Just across the street, Frazier attended “Colored school No. 4” under the influential leadership of New York City’s first Black principal, Sarah J. S. Tompkins Garnet. The building was granted New York City Landmark Status in 2023 and is based on an 1843 city-wide standardized design with separate entrances for boys and girls.

Black education: separate or integrated?

Locally, education for Blacks in the first half of the 19th century did not go beyond elementary school and was limited to separate schools.

The 1870 adoption of the 15th US Constitutional Amendment guaranteeing equal protection under the law regardless of race, and the 1873 New York State civil rights law, guaranteeing equal protection in hotels, restaurants and schools, prompted a debate and series of actions about separate or integrated schools.

This issue emerges in Episode 7, Season Two of the HBO series. It is important to understand that at the time depicted, 1883, Brooklyn was the US’s third largest city, and not part of New York City which consisted only of Manhattan and the Bronx.

The series depicts the real-life attempted closure of three all-Black, segregated schools in Brooklyn in 1883. In the end, in the series, the segregated schools are saved by becoming integrated.

What the series is not so good at depicting is the complexity of the issue, and the debate within the Black community as to whether separate or integrated public education was best. Many Black community leaders argued for integrated public schools, but that was based on one important condition.

The key to having integrated schools be beneficial to the Black community rested on whether Black teachers were allowed to teach White students. Without Black teachers, any integrated school would function with Blacks as second class citizens with lesser roles.

While Brooklyn “broke the color line” to use the language of the time in 1883 as accurately depicted in the series, New York City (Manhattan and the Bronx) kept the practice in place until it was challenged by Susan Elizabeth Frazier in 1895.

Susan Elizabeth Frazier had graduated from what is today Hunter College in Manhattan, a prestigious “normal” school dedicated to training teachers. She was offered a job as a teacher in an integrated school on the upper west side of Manhattan until she arrived and it was realized she was a woman of color. The offer was retracted. This is reminiscent of the fictional scene where Peggy Smith was invited to have her writings published in The Christian Advocate, until she arrived in person and the unconditional offer was retracted.

Although Frazier lost in court, she eventually won in the court of public opinion which involved nation-wide interest and news coverage. She was granted the position she sought in 1896 at School No. 58 on West 52nd Street between 8th and 9th Avenue, becoming the first teacher of color to teach White students in New York City.

Above: Left, integrated “School No. 58” where Frazier eventually became a teacher of White students. A newer building is on the site today, but it remains a school.

As if her many years as a public-school teacher in New York City were not testimony enough to her success (she taught until she died in 1924), she won a New York Tribune newspaper contest in 1919 as the “city’s favorite teacher.” What was particularly meaningful to the Black community at the time was that the old argument was that White students would leave any school with Black teachers. Given the volume of the voting, it was clear that many White persons admired Frazier.

The prize was a trip to the battlefields of Europe, given the recent successful conclusion of World War One. This was particularly apt because Frazier founded and led the Women’s Auxiliary of the Black combat troops, the highly decorated Harlem Hellfighters. She was the first Black woman to receive full military honors at her funeral at the Harlem Armory, before burial in Rhinebeck.

The HBO series does not (yet) go beyond 1883, so we do not know what is in store in the later life of Peggy Smith. But the combination of being a skilled writer, and a courageous and persistent trailblazer, served the real-life Susan Elizabeth Frazier well in advancing the cause of both Blacks and women.

Let’s conclude with the words Frazier used to conclude her 1892 speech to the Brooklyn Literary Union, “We young women of the race have a great work to do. We have noble and brilliant examples of women who, under all trying circumstances, have labored earnestly for the elevation of their race, their sex. Let us strive with the advantages of a higher education to carry out the aim of our noble predecessors.”

Right: The AME Church Review published a landmark speech given by Susan Elizabeth Frazier at the Brooklyn Literary Union, February 16, 1892. Click here to read the full speech.

Above: The actor Melanie Nichols-King plays the real life character of school principal Sarah Garnet (seated). Garnet was principal of Colored School No. 4 when Susan Elizabeth Frazier attended as a child. She would have been an influential role model.

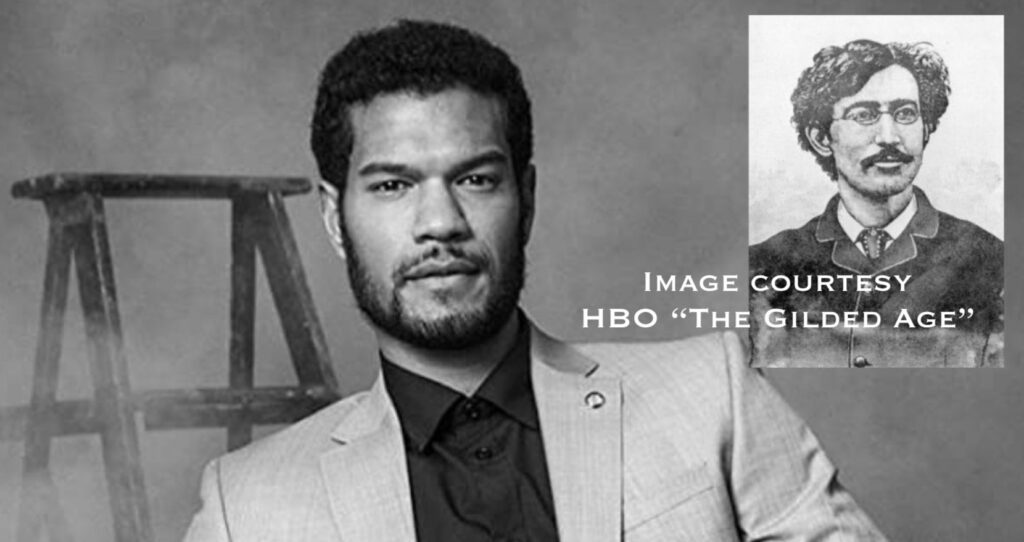

Above: Actor Sullivan James portrays the real life editor and publisher T. Thomas Fortune (inset). Fortune and Frazier were both known as advocates for integrated organizations, whether that was the YMCA or public schools. But the Black community was split as to which path offered better opportunities. The key to the integrated approach to public schools being positive for the Black community involved Blacks being teachers of White students.

Above: A recently erected headstone marks the grave of Susan Elizabeth Fraizer, visible between the headstones of her grandfather Robert, left, and great-grandfather, Andrew Frazier, right. Andrew Frazier served in the Revolutionary War and received a veterans pension later in life. He lived to be 102 years old.

Click below for more on the Gilded Age: