By Bill Jeffway

A version of this article appeared in the July 10 issue of the Northern/Southern Dutchess News.

Beauty, they say, is in the eye of the beholder. That is certainly true among the summer wildflowers we find around us in Dutchess County. Whether a non-native flower is a thing of beauty, or a noxious enemy to be eradicated, or both – can be seen in the evolving narratives surrounding purple loosestrife (lythrum salicaria) and oxeye daisy (leucanthemum vulgare).

From its founding in 1914, the Dutchess County Historical Society has always included the study of plant life as a fundamental part of understanding of our local history.

Perhaps the best-known contribution is the collaboration of DCHS’s Helen Wilkinson Reynolds and photographer Margaret DeMott Brown, and the brilliant Vassar College Professor and Botanist, Edith Roberts. Together they published the landmark The Role of Plant Life in the History of Dutchess County in 1938. Its many pages include charts, maps, and photographs as well as narrative.

But for this exercise, we will draw from the charming and conversational 1931 publication Stories of the Wildflowers by DCHS founder Dr. J. Wilson Poucher. It was a summary of a series of local newspaper columns.

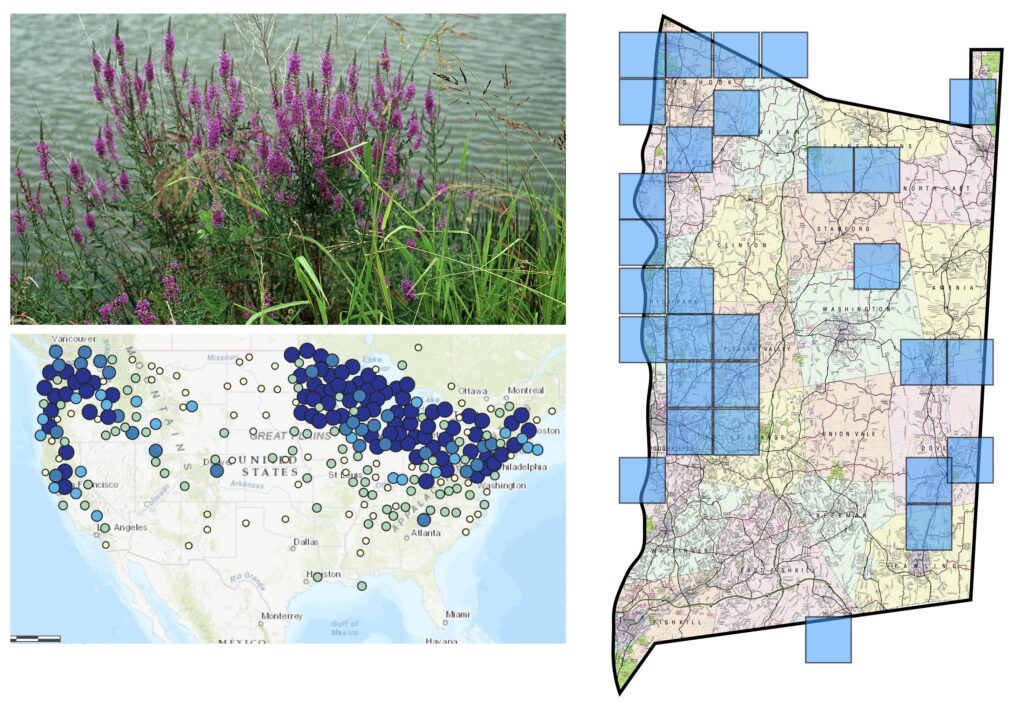

Purple loosestrife grows in tall narrow strands that can easily exceed four feet in height. They grow in marshy areas from August into September into broad, sweeping walls of color.

Poucher reports that locals, right after the Civil War (so in the late 1860s), upon noticing the emerging purple loosestrife, gave it the name of “Rebel’s Weed.” At the time it was said to have been brought back (whether intentionally or accidentally it is not reported) by northern soldiers returning from battles in the southern U.S.

Poucher wrote in 1931, “There is a prevailing tradition that it was in some way brought home by the returning soldiers of the Civil War and the common name for it at the present time among the good people along the Wallkill (in Ulster County) is Rebel Weed. I am inclined to believe that is simply a coincidence. I can find no account of it growing anywhere south of Delaware. It is not a native, but one of the many wildflowers imported from Europe. It gradually spread from marsh to marsh, from the Wallkill to the Hudson River, then gaining a foothold in Duchess. It appeared for several years in clusters here and there until, at the present time (1931) it fills all our marshes. I do not know anything that surpasses the beauty of the view in late summer.”

Indeed, Poucher was right about its origins. It originated in Europe, not the southern United States and appears to have been introduced after 1830 and now covers a wide area of North America.

Time was kind to the flower as the negative connotations related to the use of the word “rebel” and “weed” were lost as that name went out of fashion. By the 1940s we could expect to find Eleanor Roosevelt writing about the beauty of purple loosestrife on her Val Kill estate in Hyde Park each August in her nationally syndicated My Day Column.

Today, however, there is no doubt that purple loosestrife is an invasive plant that crowds out both plant and animal life and biodiversity.

There is another non-native wildflower that was initially falsely attributed to the “rebels” of the southern U.S.

Dr. Poucher actually gave more credence to the idea that the oxeye daisy came from the south. Poucher described the oxeye daisy as “first seen in Georgia after Sherman’s army had made its famous march through that state to the sea…the seeds were very likely to have been transported in the hay that every army carries along as fodder for its horses.”

No contemporary account of the origins of the oxeye daisy in the area describe such a possibility, instead its source is credited to Europe and western Asia. It is generally understood that its introduction was much more likely an intentional introduction because of its simple beauty and hardiness. It is now described as “naturalized” across the continent indicating it has comfortably settled in for the long haul.

The conundrum is reflected in two articles in the Poughkeepsie Eagle News in the late 1800s. In 1897 we find instructions on how to create a delightful hat for a young girl out of oxeye daisies. Two years later, in 1899, the same newspaper published an article under the heading “How to destroy the oxeye daisy,” declaring it can be eliminated “if precaution is exercised.”

No doubt both “weeds” flourish because they are at the same time invasive, and beautiful in the eyes of many.