Pine Plains and the Loss of the Small Family Dairy Farms

By Dyan Wapnick.

This article was first published in the 2023 DCHS Yearbook, Vol 102, Farming in Dutchess County. Dyan Wapnick isthe president of the Little Nine Partners Historical Society of Pine Plains, NY, and an executive producer of their documentary, “Our Farms, Our Farmers” which you can view below. She is also DCHS Vice President for Pine Plains. She has a BA in history.

Imagine you could travel back in time to Pine Plains at the turn of the twentieth century. Standing at the intersection of Main and Church Streets you might catch the whistle of the Poughkeepsie and Eastern train as it leaves the Borden Creamery at the P&E station, where local dairy farmers dropped off their milk twice a day in 10-gallon aluminum cans – fully loaded weighing over 80 pounds1 – to be processed and shipped. Every Tuesday was cattle day, in which a cattle car was placed at the Newburgh, Dutchess and Connecticut railroad stockyard on South Main Street and where farmers drove their beef cattle to be transported to New York City. With 18 trains going in and out of the hamlet daily, it was a busy place, and a lot of that activity revolved around the farms.

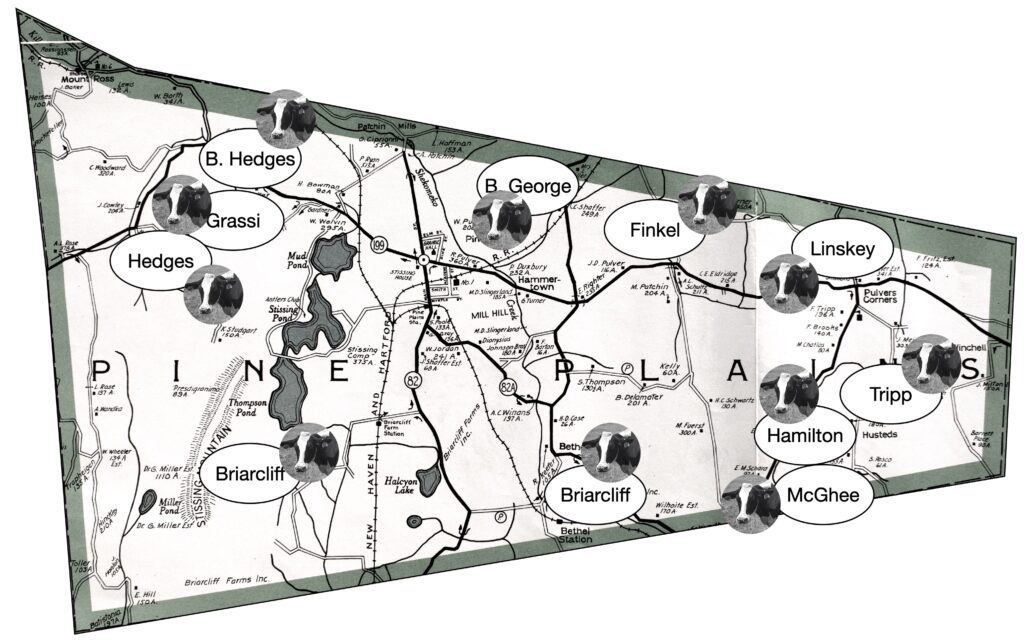

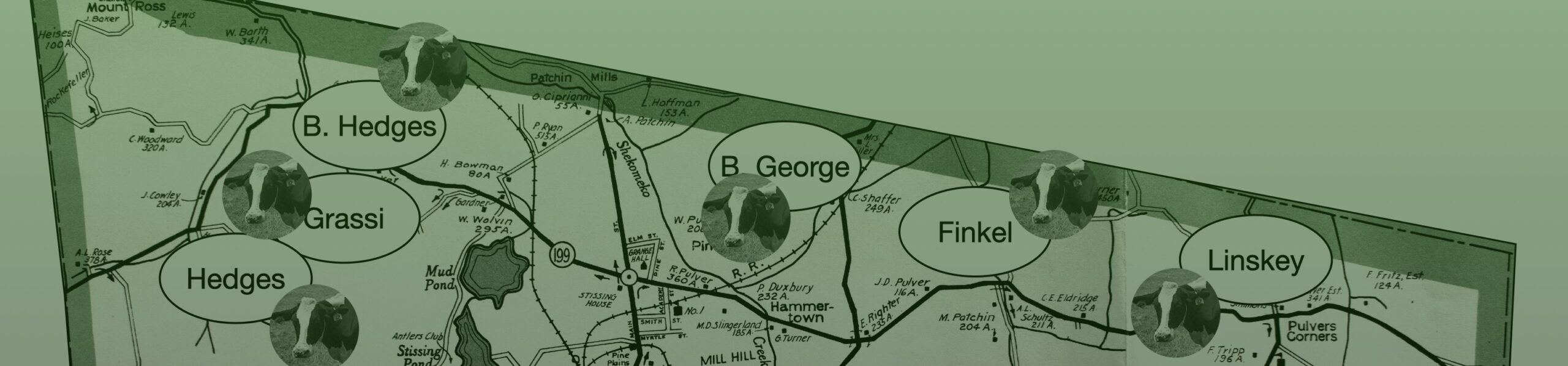

Today you would be hard pressed to picture this peaceful hamlet sequestered in northeast Dutchess County capable of supporting two weekly newspapers (the Pine Plains Herald and Pine Plains Register), two drug stores (Bowman’s Pharmacy and Cole Drug Store), two large hotels (the Ketterer Hotel and the Stissing House), several boarding houses for the tourists (including The Pines, a 25-room mansion), Bowman’s Opera House, multiple shops, and a renowned school (Seymour Smith Academy), not to mention over 40 small- to mid-sized family farms dotting the surrounding countryside and nearby communities. Yet that’s how it was in 1900.

This article will attempt to show how the loss of these farms, with a focus on dairy farms, has had a direct, negative impact on the vitality of the once-thriving hamlet of Pine Plains.

Looking down South Main Street from the intersection, with the Stissing House on the right and the Ketterer Hotel on the left. Before 1920. Property of the Little Nine Partners Historical Society

If you could stand on the same spot in 1935, other than horse and buggies replaced by automobiles, you wouldn’t see many changes from 35 years earlier despite it being the middle of the Great Depression. Sure, the opera house closed, but now there’s a popular cinema across the street, the Pine Plains Theatre, which is also a testing site for first-run films before they debut in New York. There’s a clock tower next to the Stissing House, memorializing long-time Doctor Henry Clay Wilber. Yes, the two weekly newspapers have merged into a single weekly, the Register-Herald, and Seymour Smith Academy was recently torn down, but it’s been replaced by the Pine Plains Central School, the first centralized school district in Dutchess County. The tourists continue to flock here every summer, with boys’ and girls’ camps on Stissing Lake owned by the parents of future composer and lyricist Jerry Herman (a camper here from the age of 6 to 23, and later the camps’ musical theater director). A former large dairy enterprise called Briarcliff Farms just south of the hamlet ceased operation, but it’s now an Aberdeen Angus championship beef farm supplying the stock for 95% of the Angus cattle in the United States.

However, by the end of the decade the railroad was no more, with the last freight service in 1937 and the tracks eventually all pulled up; yet if you were to stand on that same corner in 1950 you might be surprised to see the railroad’s demise has not had a noticeable effect on the community. Truck transport has taken the place of the trains, and in the years since World War II, with the help in part of the GI Bill which provided loans and educational opportunities for farmer veterans, Pine Plains has continued to flourish, looking much the same as it did 15 years earlier. But change was coming—and when it came, it changed the life of the hamlet.

Pine Plains hamlet mid-20th century. Property of the Little Nine Partners Historical Society

Beginning in the 1960s, a small-town version of urban renewal began to take place in the hamlet. One of the first buildings to go was a beautiful Greek Revival on Church Street , the Davis House, torn down in 1963 to make way for a Grand Union. By 1970, the former Ketterer Hotel on the corner, last known as the Piester Building, sat vacant, and it was demolished in 1974, leaving an empty lot in its place, while the venerable old Stissing House on the opposite corner had become the local watering hole, in danger of suffering the same fate. Also in 1974, Berlin’s Department Store on the northeast corner was torn down to allow for the Stissing National Bank’s expansion. Fire destroyed several buildings on South Main Street (in 1981 and 1992), which became more empty lots. The old movie theatre closed and was slated for demolition until a last-minute reprieve saved the building and it was converted into Pine Mall, supporting businesses on three floors. But that, too, failed and it became another abandoned eyesore.

The decline didn’t happen overnight, and it was not unique to Pine Plains. The seeds had been sown quite a few years earlier, ironically during a period of progress and growth, the result of technological changes and other factors which directly influenced the number and size of dairy farms. (According to the USDA, dairy farm size can be classed by headcount, with small farms having 30 milk cows, mid-sized farms from 30-500 milk cows, and large farms anything over that number).2

You can’t talk about the development of Pine Plains without including the railroads, which transformed this rural community in the boom years after the Civil War. Pine Plains was uniquely situated to take advantage of the east-west rail traffic afforded by the so-called “short lines” in Dutchess County. At its peak, there were three railroads serving the town. While they all provided passenger service, it was in the hauling of iron ore and milk that they expected to make money, and among the sales pitches used to entice Pine Plains residents to invest in the first of them to be incorporated, the Poughkeepsie & Eastern (1872), was the claim that their farms would gain 25% in value within three years of its completion. For what had been mostly subsistence farms, the railroad opened up new markets, especially in New York, and once refrigerated rail cars made it possible to ship raw milk by train, production escalated to meet the demand and farmers began increasing the size of their herds.

In 1907, Briarcliff Farms came to Pine Plains and began buying up 12 small-to-medium sized farms, totaling 3,249 acres south of the hamlet. Farm consolidation, the absorption of smaller farms by larger ones, was nothing new, but this was the biggest single acquisition the town had ever seen, and from an outside source at that. The railroad provided one of the main justifications for moving this industrial-sized dairy operation from Westchester County to Pine Plains. If the $55 per acre paid for the Phoenix Deuel holdings was typical –$30,000 then, the equivalent of almost $1,000,000 today – you begin to understand why the local farmers sold out and how this set the stage for what was to come.

For the time being, the small family farm continued to be the mainstay of the dairy industry, helped along by several advances in agricultural technology during the early 20th century that made farming less labor-intensive, such as innovations in tractor design, the development of the self-propelled grain combine, and automatic hay-balers and milkers. Increasing mechanization meant greater efficiency, and dairy farms were now able to produce more milk with fewer workers and fewer cows: from 1950 to 1975, the average number of milk cows on farms declined by over 49%, while milk production per cow nearly doubled.3

However, by the second half of the century we see a gradual shift away from the “many farms with fewer cows” model to fewer but larger farms where more milk could be produced at lower cost. While the total number of dairy farms across the country fell by over 97% from 1940 to 1997, the size of farms increased, largely the result of consolidation.4 As reported in a 1951 article by the News-Republican of Millerton, NY, and Sharon, CT., “nearly a quarter (24 %) of all sales of farms were to buyers who were enlarging their farms.” 5

One technological change that hurt small farmers was the introduction of large, refrigerated holding tanks for storing milk. The very first of these used in the area was on the Alfred Rose Farm in Pine Plains in 1948.6 This meant no longer having to lug the heavy aluminum cans to the local dairy, as the milk could be picked up right from the farm and bulk-shipped by truck to a large processing plant miles away. By 1957 the Borden plant in Pine Plains closed. Unfortunately, the installation of these tanks was prohibitively expensive for small farms, just one example of changes that favored large farms over smaller ones. A side effect was the loss of opportunities for socializing and business dealings when the farmers came into the dairy with their milk cans.

There was a time when most farms were passed down in one family, generation to generation. However, by the mid-1900s, faced with financial hardship in their future and with new, more dependable employment opportunities such as IBM becoming available, many children of farmers turned away from farming for their livelihood.

Once predominant across the Pine Plains landscape, the small family farms provided the hamlet its economic base. They were the glue that had held the community together since the early 1800s. According to the town’s comprehensive plan, while agriculture (farming, forestry, fishing, and hunting) was the third-largest employer in 2015, it accounted for just 7.7% of jobs.7 As Successful Farming Magazine points out, farmers have historically depended on local businesses.8 Fewer farmers meant less spent on consumer goods, which had a direct impact on the businesses in the hamlet. As these farms disappeared in the 1950s and 1960s, even as the population of the town remained fairly stable, the businesses in the hamlet gradually went with them.

Although there are fewer farms today, the Pine Plains area remains agricultural, and reminders of their continued presence among us are everywhere, whether it’s the annual Future Farmers of America fair at the high school, the familiar names in the livestock barns at the county fair, the tractor dealership on the edge of town, the occasional farm vehicle encountered on the road, the pungent smell of manure in the air, or the availability of locally-produced dairy products and meat in the neighborhood supermarket.

However, farming today is about managing risk. One way is by opening up farm stores and selling directly to the consumer. Another way is through diversification, which for dairy farms means having other sources of income outside of milk production, often with changes in how the land is used. According to Chaseholm Farm’s Barry Chase, the soil in Pine Plains is very productive, ideal for growing crops such as corn, soybean, and hay, with some used locally and the rest sold internationally. There has also been an influx of vegetable, herb, and flower farmers who rent smaller pieces of land and take advantage of farmers’ markets as far away as New York. Agritourism could be a future endeavor.

Some former farms have found new life in other capacities. A few have become horse farms. A game preserve and polo club are now located where Briarcliff Farms once was. Yet the sight of fallen-down barns and silos standing alone in empty fields is all too familiar, bearing silent witness to once viable farms that were simply abandoned, and much of this vacant land is still undeveloped. With its mission of preserving open spaces and the rural character of communities like Pine Plains, some farmland has been acquired as conservation easements by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Dutchess County Land Conservancy. Forty-three acres have been proposed for the site of a different kind of farm, a solar farm.

So, let’s revisit that same corner today (2023). The Pine Plains hamlet seems to be experiencing a resurgence, gradually transforming into something akin to a “destination.” This has undoubtedly been aided by the restorations of two previously-mentioned key fixtures that are drawing people to Pine Plains: the Stissing House, now a world-class restaurant, and the former Pine Mall, now the Stissing Center, an arts & entertainment venue.

Pine Plains’ residents will need to continue to find new, innovative ways to reinvent their community to be less dependent on farming, while still supporting our farmers and honoring the town’s rich agricultural heritage. After a few decades of uncertainty, signs are hopeful that this is what is happening in Pine Plains; check out the view from the corner of Main and Church in another 20 years.