Clowes Research Reveals Unknown Dimensions of Another Local Artist

By Bill Jeffway

A version of this article appears in the December 14, 2022 issue of the Northern / Southern Dutchess News.

The portrait painter James Wright has been best known locally for his 1861 portrait of Matthew Vassar. Commissioned by Vassar in 1860, it is in the collection of the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College. Among the reasons it is so striking is the eight-foot height of the canvas. Vassar is shown with his dog, and his emerging Poughkeepsie estate, Springside, in the background. Wright is better known nationally for portraits like Daniel Webster, exhibited in the US Capitol.

We were prompted to want to know more about Wright because, in preparation for the exhibit of the works of Caroline Clowes currently at Locust Grove Estate we discovered through her many letters that she had both a professional and social relationship with Wright for decades. Both were born in Hempstead, Long Island, although Wright was a generation older than Clowes. Both had lifelong relationships with family in Hempstead and Wright is buried there.

Wright was a central character in Clowes’s professional advancement because he first successfully introduced her work to the influential Goupil’s Gallery in New York City in early 1870.

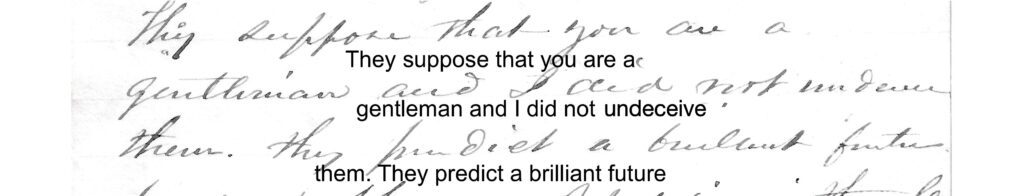

Clowes signed her work with her initials, “C. M. Clowes.” This decision is more calculating than might appear at first glance to 21st century readers. Clowes was among the very first women to make a breakthrough to become both an artistic and commercial success in the field of painting. In one of the most telling twelve words among thousands of letters, on February 7, 1870, Wright wrote to Clowes from New York City explaining after introducing her work, “They [Goupil’s] suppose you are a gentleman, and I did not undeceive them. They predict a brilliant future for you.” He went on to say he would not correct their misperception until her reputation was firmly established, which quickly happened. “You are on the right path to fame and fortune, be faithful as you always have been,” Wright went on to say at the close of his letter.

Like any good investigation into local history, we gain a few interesting answers, but acquire a greater number of intriguing new questions.

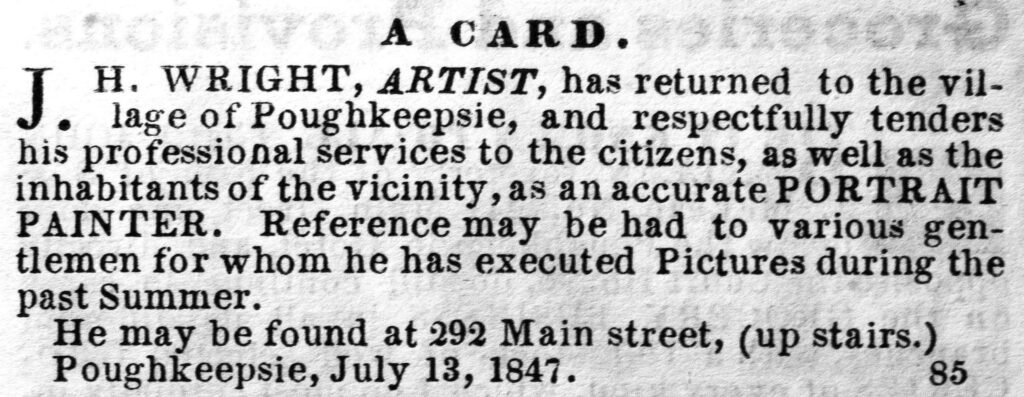

For decades he came each summer and worked from a studio on the second floor of 292 Main Street. The building that was on the south side of Main Street opposite the entrance to Garden Street. In the winter he was in New York City with a studio on Broadway near 13th Street, which was three blocks north of Goupil’s.

To our great surprise and pleasure, while reviewing the many Main Street Poughkeepsie photos in the Frank and Baltus B. Van Kleeck Collection of the Dutchess County Historical Society, we found a May 19, 1863 photo of 292 Main Street. While business owners were always eager to step outside for a photograph, the fact that the photo was taken by the highly regarded Samuel L. Walker would have helped motivate any who might have hesitated.

The sign, “James Wright Portrait Painter” is clearly seen. We know from his ads that his studio was on the second floor. A skylight is clearly visible facing north, which would have been to his advantage. Outside the door is a taller older gentleman with a hat, who could be Wright. To his right is either a young or boyish looking man who might possibly be Wright’s business partner, who we know only as “Mr. M. Morse.” In New York City they advertised their business as “Messrs. Morse and Wright’s Academy of Drawing and Painting.” This could explain why one of the school invoices for Clowes mentions painting supplies from a “Mr. Morse.”

It is through Wright’s letters that we get insight into Caroline Clowes’s commercial focus. She clearly wanted to be both an artistic and a commercial success. In the same letter referenced earlier, Wright goes over the financials relating to having her painting exhibited and offered for sale at Goupil’s, writing, “The frame will cost $32. I told him you wanted $150 clear. So he will charge $200, which less frame and commission will give you $150.”

At the time, artists could make money by allowing their paintings to be turned into “chromos” (short for chromolithography), what we would today more commonly call colored prints and engravings. Perhaps Clowes was reluctant to get involved in this type of alteration and distribution of her work. On stationary of Poughkeepsie’s Morgan House hotel, on January 7, 1872, Wright wrote to Clowes, encouraging her to be less cautious about such an endeavor. “I think you should not be so particular about chromos. It seems to me that it might do you good at this particular time to have some of your pictures published,” he wrote. If any of her works were published as prints and engravings, we have not yet been able to identify or locate any.

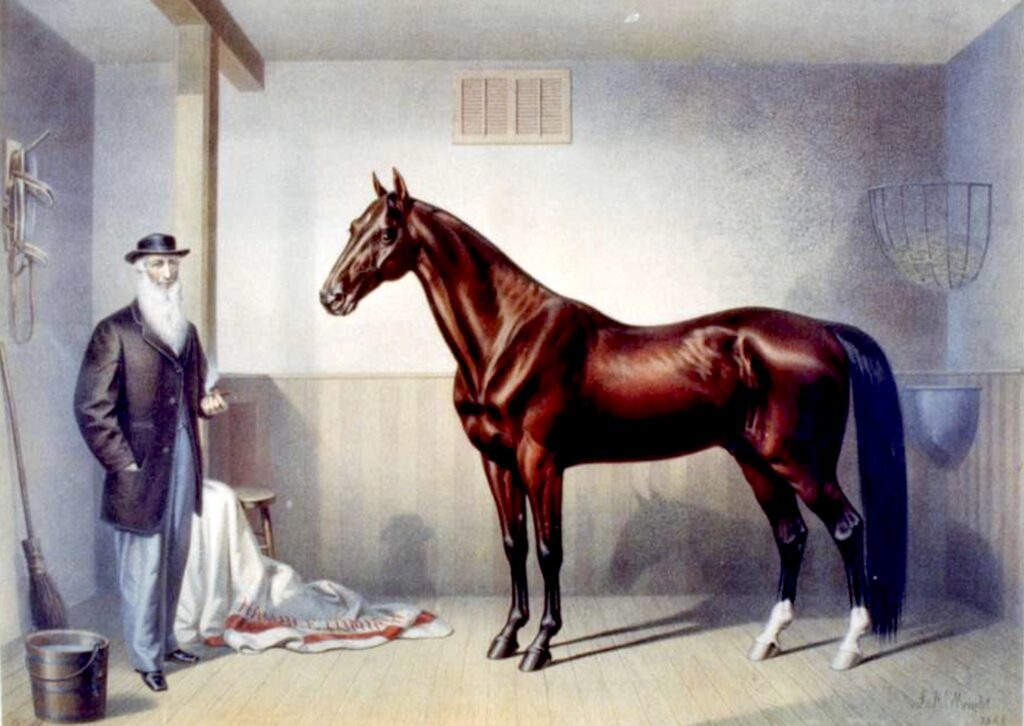

Interestingly, Wright himself, although widely known as a portrait painter, was in some instances a painter of animals like Clowes. Wright managed to have his painting of a thoroughbred horse, published as a “chromo” by none other than Currier and Ives (see photo). Wright depicted owner William Ryskyk with his horse, Hambeltonian, in a painting that was turned into a widely distributed Currier and Ives print.

The insights gained here about both artists (our richer understanding of Wright beyond his being a portrait painter, and our better understanding of the financial priorities and acumen of Clowes) come from “connecting the dots” that emerge from surveying countless letters, photographs, and old newspapers. We gain answers, which only prompt more questions. Fertile Ground: The Hudson Valley Animal Paintings of Caroline Clowes runs through December 30, details at www.dchsny.org.