A version of this article appeared in the June 30 Northern/Southern Dutchess News/ Beacon Free Press.

In April of 1867, 18-year-old Emily Hart started to carefully assemble her “herbarium,†a 48-page book of carefully pressed flowers (DCHS Collections, Gift of E. Stuart and Linda Hubbard). On each page, beneath the pressed flower, she wrote the latin name, the common name, the date and whether the flower was picked near her home in LaGrange, or near her school, Cottage Hill, in Poughkeepsie. A piece of wax paper protected it from prior and following pages.The entries run from late April to early June.

In June of 1930 at the age 81, Emily Hart was exhibiting roses at the Poughkeepsie Garden Club, and no doubt did so a few more times before she died in 1934. But the age of innocence had passed by this decade. Garden clubs were not just pleasant social groups, they were increasingly aware of the existential risks faced by wildflowers and native plants, and acted aggressively to protect them.

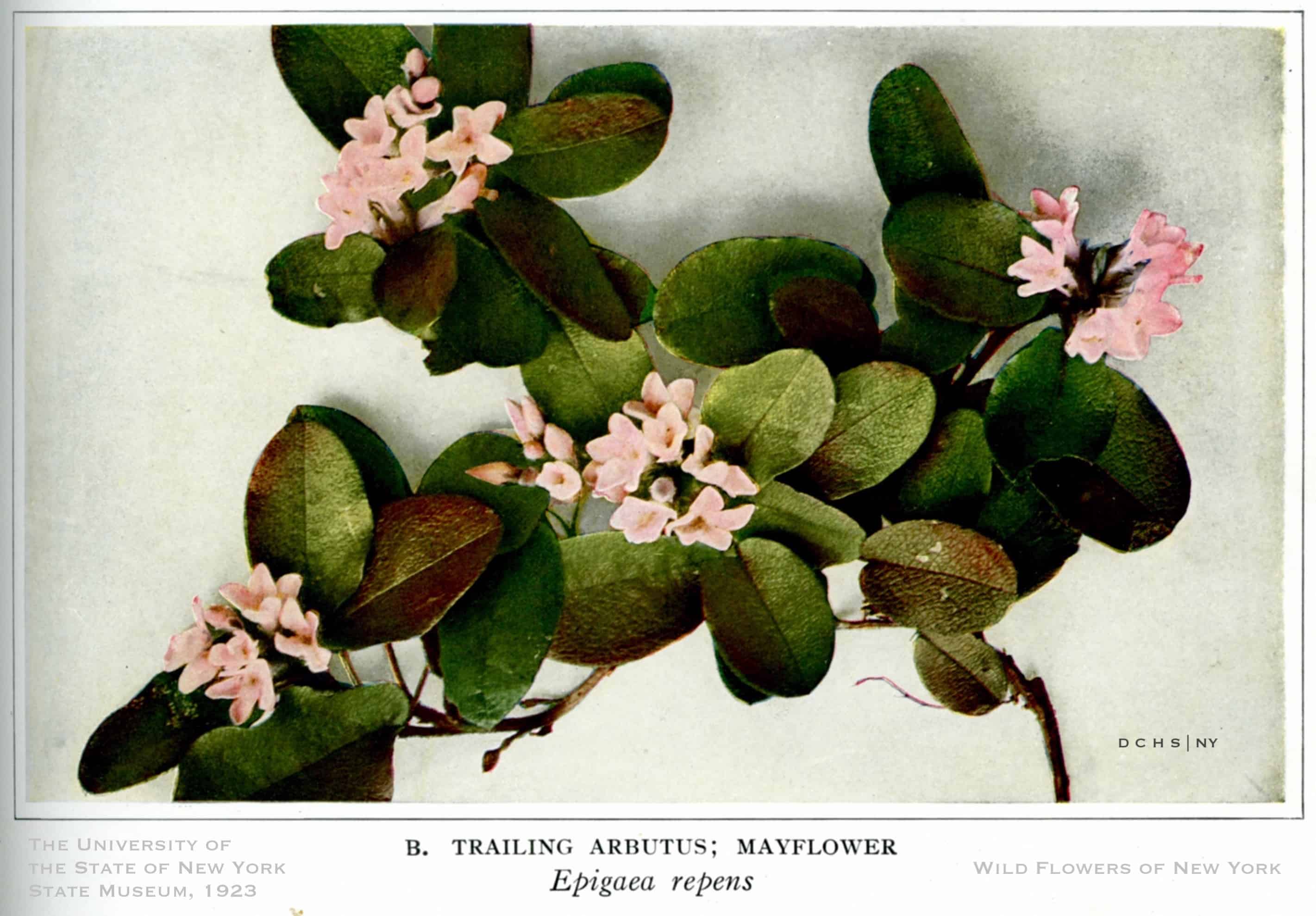

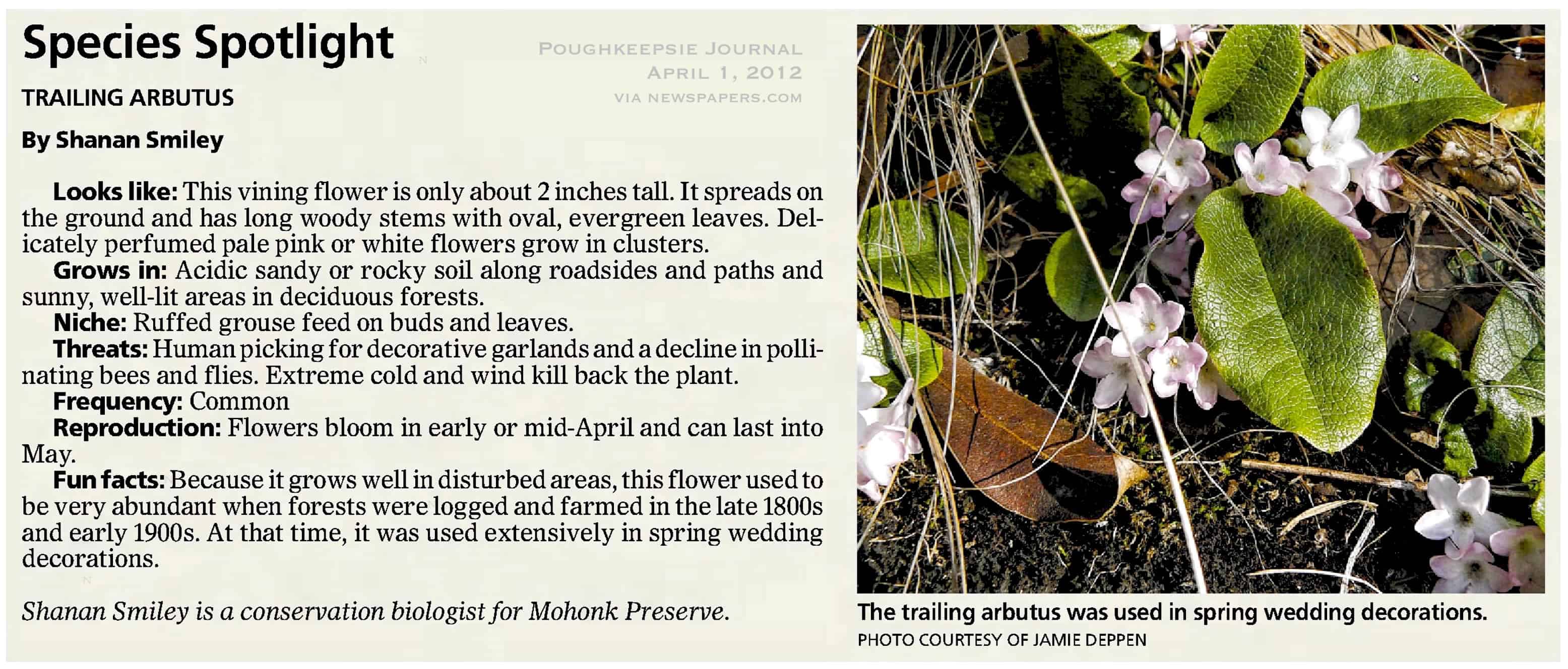

Let’s look at the change in understanding that occurred across Emily Hart’s lifetime, and into ours, through the lens of the wildflower known as trailing arbutus (called trailing because it is so low to the ground). The popularity of the arbutus was due to the fact that it flowered so early in the spring that it often encountered snow. This wildflower became the symbol of spring’s beginning, and many hopes and wishes were tied to its first appearance.

Judge Hasbrouck held the distinct title of first to wear a sprig of trailing arbutus on his label for decades.

In 1915, the local newspapers wrote about Poughkeepsie’s Judge Frank Hasbrouck saying, “As far back in the history of Poughkeepsie, as far back as the memory of the oldest inhabitant can go, Hon. Frank Hasbrouck has always had the honor of being the first Poughkeepsian to wear trailing arbutus.†In April of 1915 Hasbrouck was knocked aside as standard bearer when two prominent men in the city beat him to it by putting a sprig of arbutus in their jacket lapel buttonhole. By the following year, it was reported that Hasbrouck had restored his number one place. All this to and fro highlights the prominent place of the arbutus flower.

These more carefree days were to change as the 20th century evolved and especially by the1930s. Three local individuals in particular, staked out the grim reality and challenge for arbutus, and other wildflowers among a total of nearly 2,000 native plants.

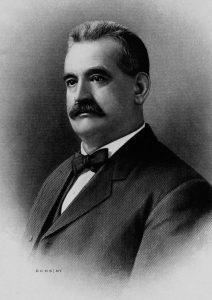

Dr. J. Wilson Poucher was a medical doctor born in Columbia County but trained in Germany. He was a founder of the Dutchess County Historical Society in 1914. In 1931 he published the book, “The Story of Wildflowers in Dutchess County†and recanted tales of his hikes through the woods and streams of the county since childhood. In his book, he repeatedly called out harvesters of local wildflowers as the number one threat, harvesters such as Judge Hasbrouck, for example, who treasured it ripped out of its natural surroundings.

Poucher had no patience for such people. Of one woman he wrote, “This lady was a flower lover, but she liked her flowers dead.â€

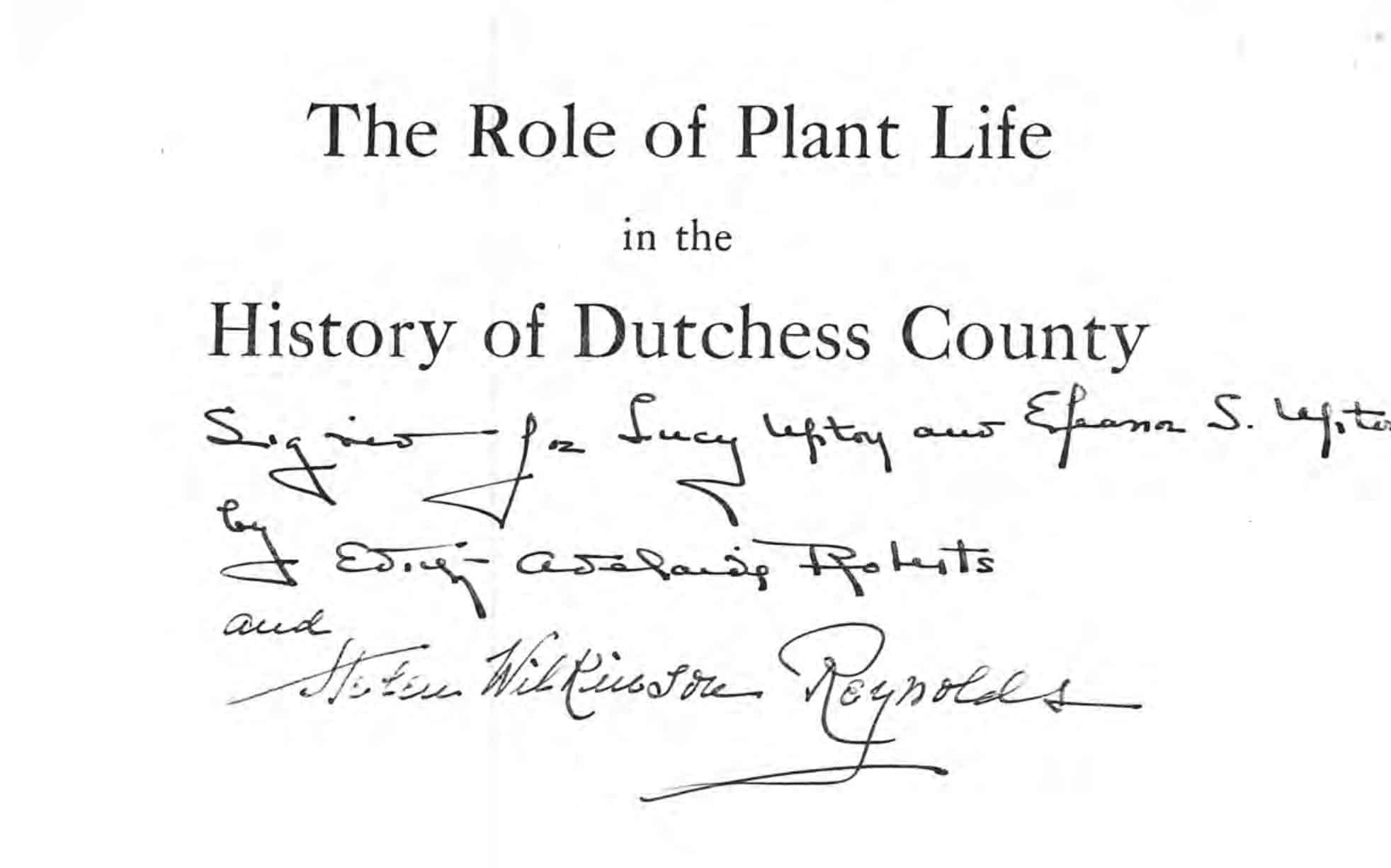

Vassar College Professor Edith Roberts published “The Role of Plant Life in the History of Dutchess County†in 1938, working with the dynamic DCHS researcher Helen Wilkinson Reynolds.

Roberts had founded a four-acre outdoor ecological laboratory at Vassar College in 1920. Faculty and students tramped through the county getting specimens of nearly all of the 2,000 plants native to Dutchess County. She was methodical and measured and spoke and wrote nationally.

Rene DuPont Donaldson, in 1937, moved with her husband to Deep Hollow Farm in Millbrook. Upon arrival, she immediately cultivated a garden of native plants. Among them was the trailing arbutus. Decades later, in 1961, the difficulty of cultivating this wildflower is revealed by no less than the New York Times in the headline, “A Growers Success With Trailing Arbutus†and the related story of the rare achievement.

Donaldson was the motivating force behind the native plant garden at New York Botanical Gardens and offered her services locally, as a consultant.

A Poughkeepsie Journal editorial in December of 1963 reported, “The trend in this direction [native plant conservation] may be more pronounced in Dutchess County than in the nation generally for there have been militant forces at work on behalf of [it].†They go on to describe Mrs. Donaldson’s work and the work of Garden Clubs. Today’s Millbrook Garden Club recognizes Mrs. Donaldson on its website.

By the 1960s it was not just people overharvesting that was the problem. Municipal roadside management of vegetation was far more likely at the time to have seen chemical sprays than the mowing and cutting you see today. Development was obviously on a much bigger scale.

In 1974, a New York State law prohibited the picking of 34 wild plants including trailing arbutus. By comparison, Connecticut passed a law protecting the trailing arbutus in 1900. It was reported at the time to be the first law of its kind in the United States.

Where are we today? Locally, the trailing arbutus is hard to find, although it was a “spotlight species†in the Poughkeepsie Journal in 2012. Barbara Hughey, a DCHS member, supporter and Yearbook author — and owner and operator of Land Stewardship Design, says that nothing short of careful attention can make a difference, but it can indeed make a difference.

On Sunday, July 19 at 2:00 pm, DCHS will hold its first virtual annual meeting (only 15 minutes) followed by a presentation by Mark Morrison on “Life’s Essential Tools: Garden Implements over the Centuries.†More info and registration (email required) at www.dchsny.org/july19 .

By the 1930s, Garden Clubs in Dutchess County were active in raising awareness and seeking protections for native plants. DCHS Hart Hubbard Collection.