Just below you’ll find the 35 minute video introduction to the chapter, Early Life, that includes a conversation with the collections donor, Linda Hubbard. September 5, 2020.

The Early Life Chapter of the Exhibition starts here, then scroll down.

jump to I. A UNION OF PROMISE

jump to II. ELIZABETH HART, MINISTER’S DAUGHTER

jump to III. OFF TO FORESTBURGH & LUMBERLAND

jump to IV. MOTHER’S DEATH BY CONSUMPTION

jump to V. FATHER’S ECCENTRICITIES

jump to VI. UNRAVELLING, RELOCATION, REBIRTH

jump to I. A UNION OF PROMISE

jump to II. ELIZABETH HART, MINISTER’S DAUGHTER

jump to III. OFF TO FORESTBURGH & LUMBERLAND

jump to IV. MOTHER’S DEATH BY CONSUMPTION

jump to V. FATHER’S ECCENTRICITIES

jump to VI. UNRAVELLING, RELOCATION, REBIRTH

The exhibition starts here. Please scroll down to continue:

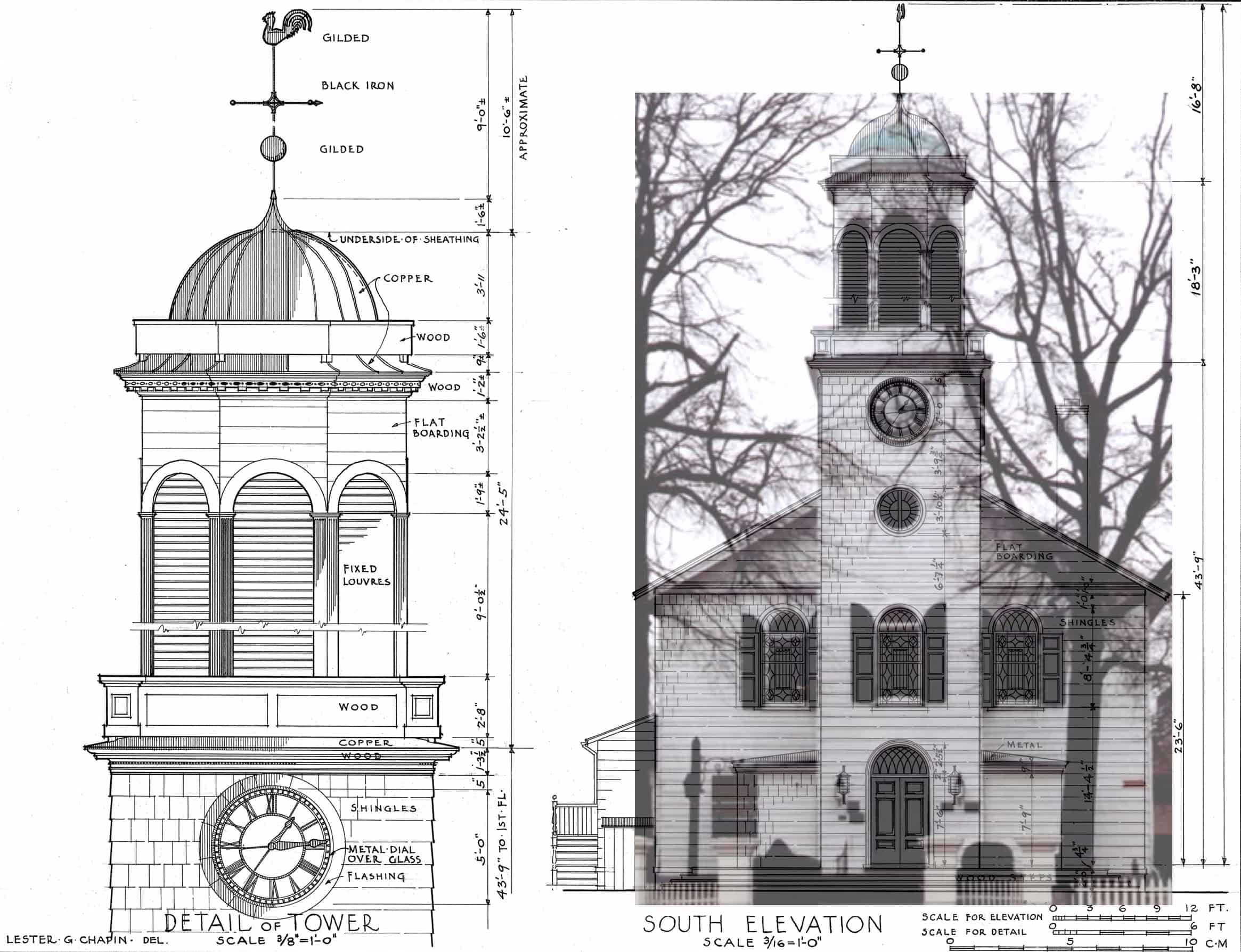

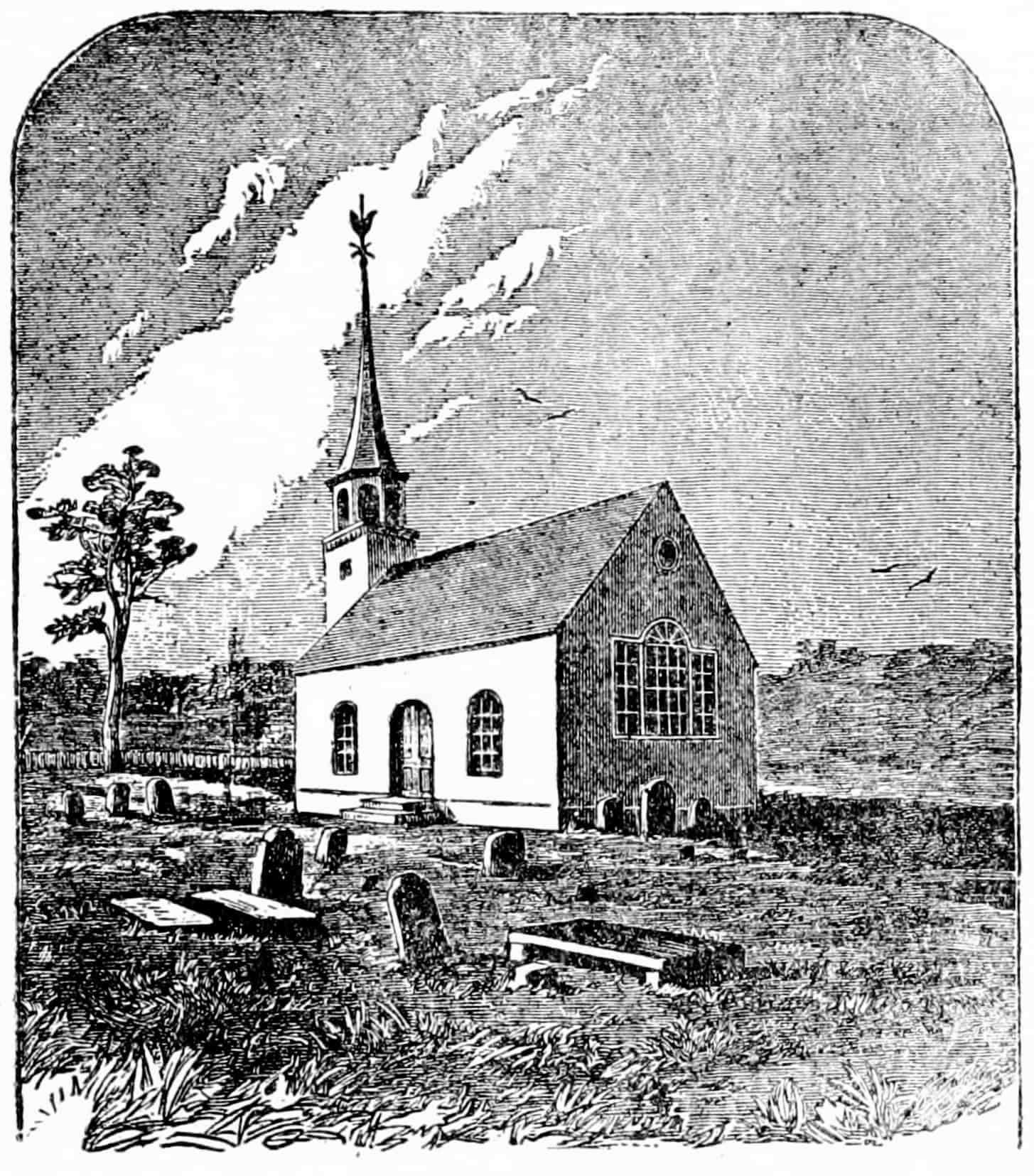

I. A UNION OF PROMISEAbove:Â Site of Caroline’s parents’ 1834 wedding, St. George’s Church, Hempstead. 1933 photo, Library of Congress. Contemporary photo, St. George’s parish.

This chapter examines Caroline’s early life, the period from her birth to age 13 when she moved in with, and was raised by, the LaGrange, Dutchess County family of the deceased mother she never knew.

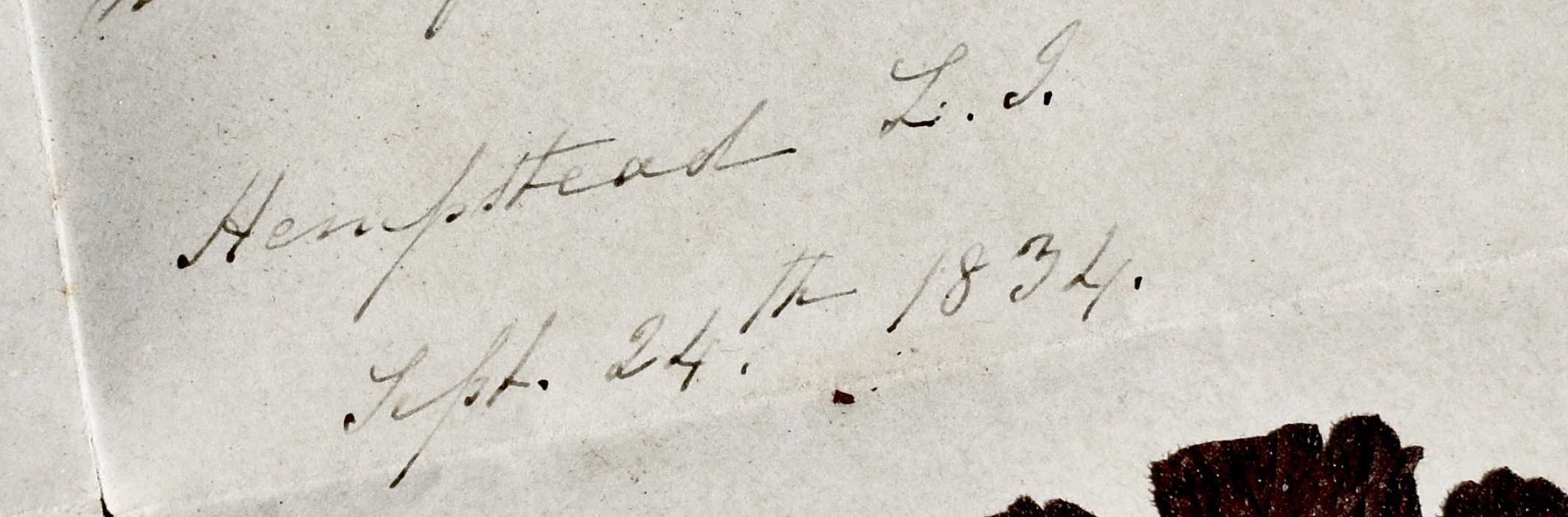

Caroline was born of two families whose brilliance could take many forms. But economic instability, and the fragility of life itself, loomed constantly amid generations of achievement. The marriage of Caroline’s parents, William Jones Clowes and Elizabeth Ann Hart, took place on September 24, 1834 at Hempstead, Long Island’s St. George’s Episcopal Church. The event would have been full of promise, and full of important guests who were leaders in business, law, faith, publishing and society — all fruitful pursuits of both the Clowes and Hart families.

Above: Silhouette of Caroline’s mother, Elizabeth Anne Hart and a later photograph of Caroline’s father, Willliam Jones Clowes. DCHS Collections.

Above: Drawings, HABS, Library of Congress. Contemporary photo, Google photos.

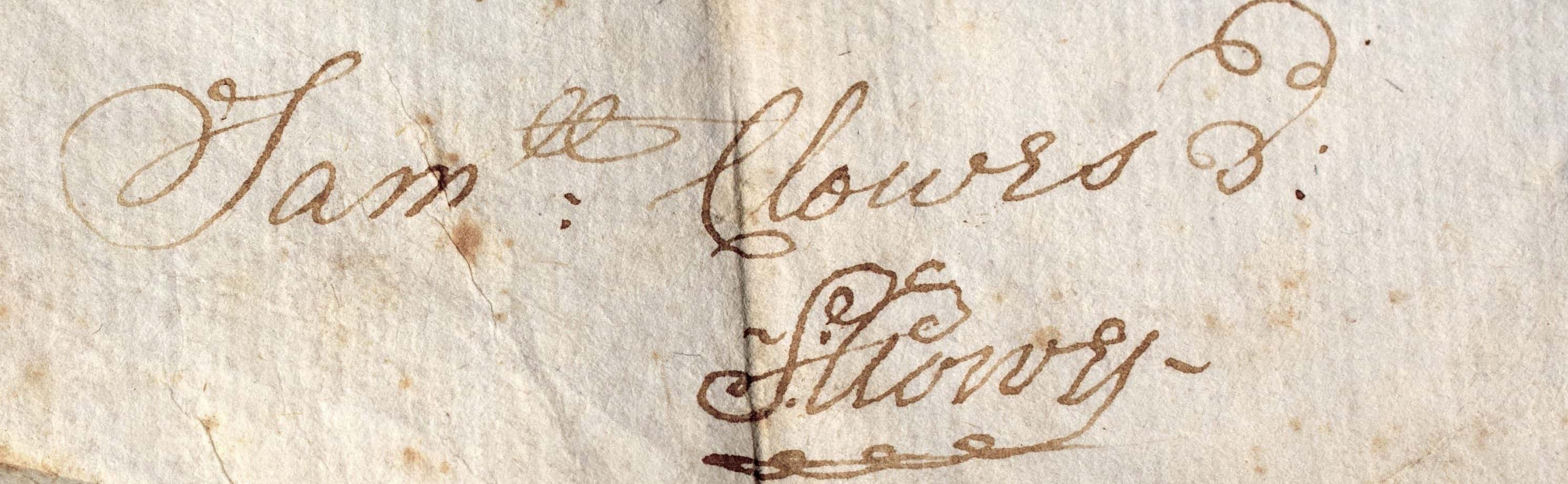

Members of the distinguished Spooner family were among the guests, one of whom wrote a poem for Caroline’s mother. DCHS Collections.

Among the thousands of family letters in the DCHS Hart Hubbard Collection is a letter that includes a poem, dated on Caroline’s parents’ wedding day. It is from “Mrs. Spooner,” who is very likely Maria Anna Bronson Spooner (1812-1900). She was married to Edwin B. Spooner, the editor of the Brooklyn Star, a popular and successful newspaper that his father, Col. Alden Spooner had founded in 1811. They would have been typical of the type of guests at the wedding that day. Read the entire poem here.

The Hart Family

Caroline’s mother, Elizabeth Ann Hart, was born of two parents who were descendants of the mid-17th century settlers of Connecticut who were part of an unbroken line of leaders in civic matters and in the Episcopal Church.

Although the Rev. Seth Hart had died two years prior to the marriage of Elizabeth and William, his presence would have been felt. As the Rector of St. George’s Church from 1800 to 1829, he was a commanding figure in the community. His tenure included leading the fundraising for, and the 1822 construction of, the beautiful Church building that surrounded them. The building still stands today.

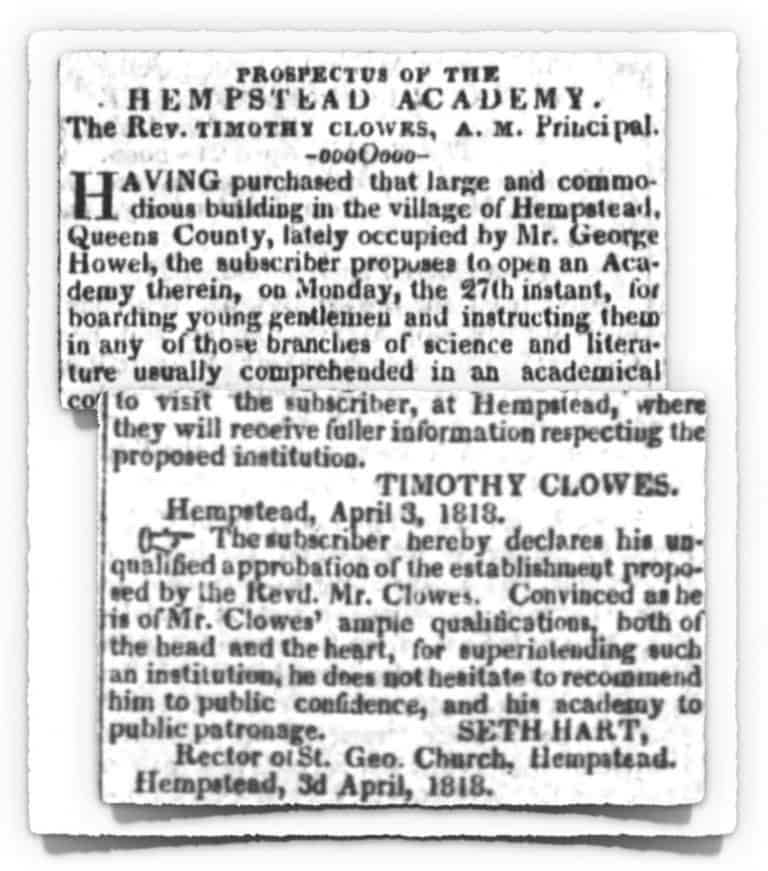

In addition to his ministerial duties, the Rev. Seth Hart taught classics like Greek and Latin and mentored and taught men on the path to ordination. He was one of the reasons that Hempstead was seen as a refined and important town. His wife, Ruth Hall Hart also possessed her own fine pedigree of 17th century Connecticut settlers.

The Rev. Seth Hart and Ruth (Hall) Hart, the latter from a painting by Caroline M. Clowes. DCHS Collections.

The Hall Family

The Hall family helped settle Hartford, and in the case of Ruth’s ancestors, the area around New Haven. Within a year of Ruth leaving her birthplace of Wallingford (just north of New Haven) for Hempstead, her two sisters relocated to Florida. Ruth’s elder sister was married to Ambrose Hull who became a major plantation owner in Spanish Florida in1801. When the elder sister passed away, the younger Hall sister became the widower’s bride, stepping in for her sister, and marrying at the original church building of St. George’s in Hempstead under Rev. Hart. They spent what would be more than two decades in an unsuccessful effort to develop land in Florida. The letters of the sisters were shared by the artist and family historian at the time, Edith Louisa Hubbard (1883-1959), and were published by the Florida Historical Society in 1952.

First or second generation Samuel Clowes signature on a 1747 Hempstead deed. DCHS Collections.

[drawattention ID=”15135″]The Clowes Family

The family’s immigrant ancestor, Samuel Clowes (1674-1740), was an advanced mathematician and lawyer in England before arriving in New York in 1697. He settled in Jamaica, Queens County, becoming the first lawyer on Long Island. One of the founders of the first Episcopal Church on Long Island, St George’s Church in Jamaica, he also served as Queens County Clerk, and a (if not the only) land surveyor in Jamaica and Hempstead. Like other wealthy, well connected families at the time, he acquired vast tracts of land in upstate New York. In Clowes’ case, his land was located across Orange and Sullivan Counties in the first division of the Minisink Patent. He founded the town of Goshen at the two counties’ border and led generations of equally successful Clowes family members in the same fields.

William’s older brother, Timothy Clowes (image below) was a graduate of Columbia College and an ordained Episcopal minister, but spent most of his life in education. He was principal of the Hempstead Academy. He founded the Erasmus Hall Academy at Flatbush where his younger brother, William, acted as Vice Principal. He was President of Washington College in Maryland, “He was one of the best linguists and mathematicians of the day. Indeed, his discoveries and improvements in the latter science were most extraordinary,†wrote historian, Benjamin Thomson.

The original church building of St. George’s Episcopal Church, Hempstead, prior to 1822.

Rev. Timothy Clowes, brother of Caroline’s father

In this 1818 notice, Caroline’s maternal grandfather, the Rev. Seth Hart, endorses the school led by her father’s brother, Rev. Timothy Clowes. Both were important residents of Hempstead.

CLICK ON ARROWS BELOW FOR DETAILS

Both Hart and Clowes family members head upstate

[drawattention ID=”15125″] Return to Early Life Index II. ELIZABETH HART, MINISTER’S DAUGHTER

Elizabeth Ann Hart was born on May 9, 1809 in Jamaica, Queens, the fifth of the seven children of the Rev. Seth and Ruth Hall Hart. Hannah, the first daughter born to the couple lived less than a year, leaving Elizabeth as the only daughter in the family. Before she reached the age of seven, two of her brothers, Henry (1799-1813) and Ambrose, (1792-1816) died, leaving Elizabeth with three brothers. The four siblings grew up as minister’s children, with certain expectations placed upon them.

Elizabeth’s oldest brother, William, was nineteen years her senior. A minister like his father, he settled in Richmond, Virginia and became a teacher. Elizabeth’s two younger brothers, Benjamin and Edmund were both sent to Virginia to be educated by him. It is possible that Elizabeth spent time there, also, for the same reason.

By 1829, William became Rector of St. Andrew’s Church in Walden, Orange County, not far from Goshen, the town founded by Samuel Clowes. Rev. William Hart had the tragic responsibility to conduct the service for Caroline’s mother’s internment at the church.

At an early age Elizabeth demonstrated an artistic proficiency with ink and water color drawing. We know this from letters, including later letters to Caroline comparing Caroline’s proficiency with that of her then late mother.

She appears to have lived with her parents in Hempstead until her marriage to William Jones Clowes, also of Hempstead. Elizabeth and William’s first child, Lydia was born in Hempstead on January 10, 1836, followed on March 3, 1838 by another daughter, Caroline Morgan.

Return to Early Life Index III. OFF TO FORESTBURGH & LUMBERLAND

Before Caroline was two years old, her parents and older sister moved from the relative sophistication of Hempstead, to a rugged, shared house among the mills of the very remote hamlet of Neversink Bridge. Her mother commented that the natural beauty of the area was powerful and provided a healthy environment for the young children to grow up in. She went on to suggest that “If I should ever aspire to the dignity of a name we might call it Chestnut Grove.â€

William, Elizabeth, Lydia and Caroline’s home from 1839

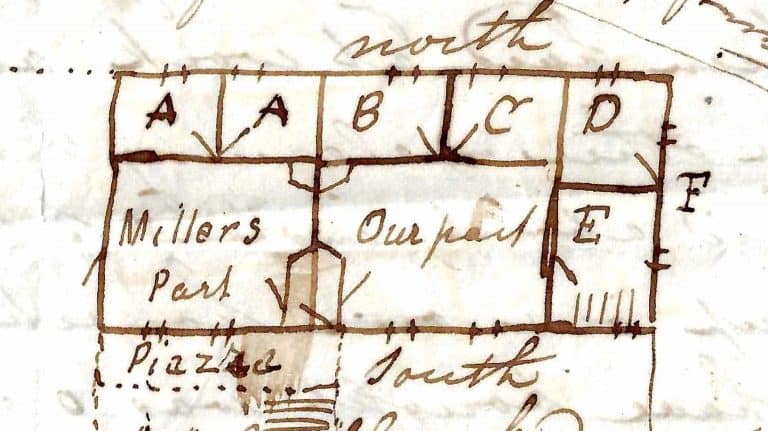

At right is a sketch of the Clowes house at Neversink Bridge (eventually Hartwood) in the town of Forestburgh that Elizabeth drew within a letter to her mother. See its location on the larger maps below. Survey records show that in August of 1830 William Clowes carved off 293 acres at the location where the Bush Kill Creek empties into the larger Neversink River. In 1839 this spot would become the site of the family’s home and William’s mother would come to live with the young family. They shared it with the Miller family who Elizabeth described as having many children and who helped with cleaning and milking.

“Store and Dwelling” refers to the Clowes’ home in Forestburgh

“Neversink Bridge” was remote by any measure

Return to Early Life Index IV. MOTHER’S DEATH FROM CONSUMPTIONDeath by consumption or tuberculosis, known as the wasting disease, was the leading cause of death in the 19th century.

Historians explain that the deadly disease that took the life of Caroline’s mother was so prevalent that it was frequently portrayed in art and literature, usually as a young woman, cut down in the prime of her life (think of Satine, played by Nicole Kidman in the 2001 movie Moulin Rouge) or an iconic, brilliant artist. The latter, it is suggested, was due to so many well known greats succumbing to the disease: Keats, Henry David Thoreau, Jane Austin, Chopin.

AÂ Golden Day Dream by Emily Mary Osborn (1828-1925). The often long, languishing aspect of consumption lent itself to heroic depictions of a long, but inevitable, struggle with death.

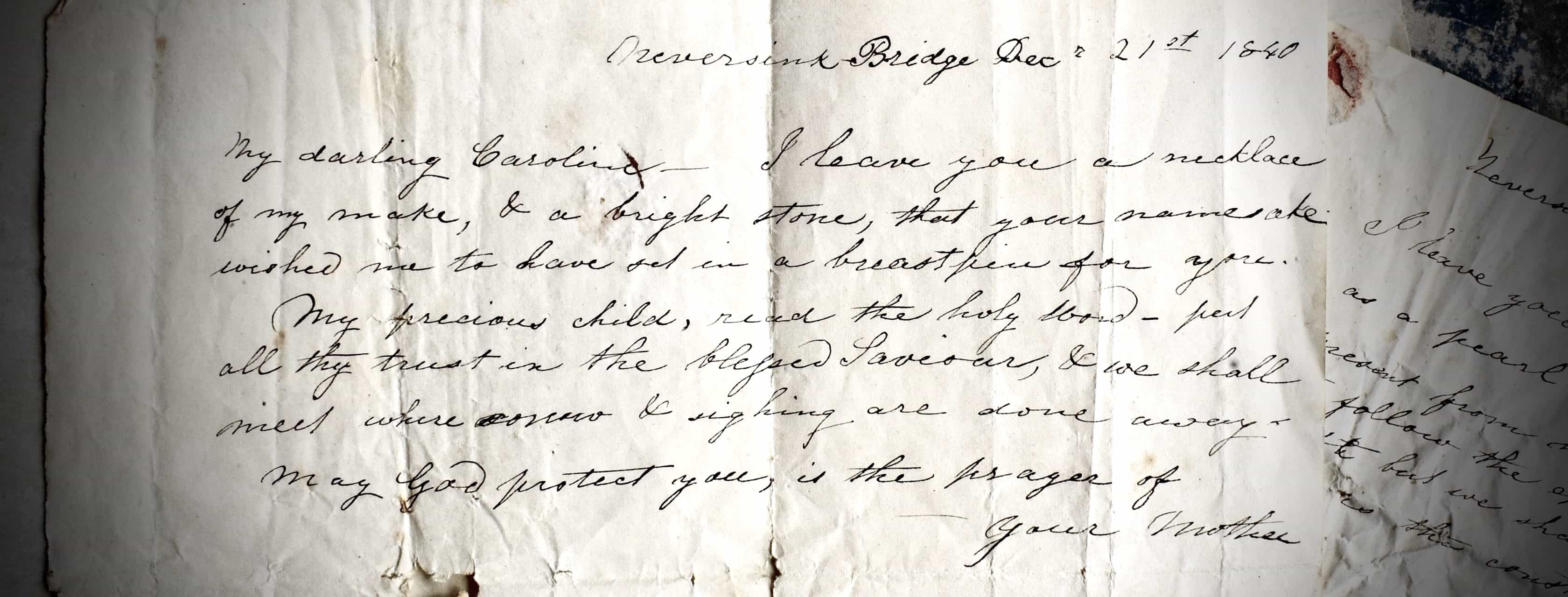

DCHS Collections Chair, Melodye Moore, in looking at the letters of Caroline’s mother over decades, finds that she first mentions her coughing just after Caroline’s birth in March of 1838. By the fall of 1840, just after the birth of her third daughter, Ellen, Elizabeth’s condition had worsened to the point that she has written deathbed letter to each of her daughters and provided her family with a list of requests regarding her funeral and burial.

Parting words, prayers for each child

DCHS Collections Chair, Melodye Moore, in looking at the letters of Caroline’s mother over decades, finds that she first mentions her coughing just after Caroline’s birth in March of 1838. By the fall of 1840, just after the birth of her third daughter, Ellen, Elizabeth’s condition had worsened to the point that she has written deathbed letter to each of her daughters and provided her family with a list of requests regarding her funeral and burial. On Christmas Eve, 1840, Elizabeth died.

William, writing to his mother-in-law, described her passing, “She had sunk into a quiet and peaceful slumber from which I was unwilling to awake her; so natural and early her sleep appeared to be to me that I was indulging the hope that her disease was taking a favorable turn until others more experienced than myself came into the room and told me that this sleep would probably be her last; – she continued in the same apparent slumber for about two hours, her breathing becoming fainter and fainter every moment until without the least apparent pain or struggle her spirit silently forsook its pale and wasted tenement and took it flight we have every reason to believe for a better and a happier world.“

Melodye Moore reads Elizabeth Anne Hart’s last letter to her mother…

Return to Early Life Index VI. FATHER’S ECCENTRICITY

Initially, Caroline’s father seemed to be following in the family tradition of taking on serious civic and religious responsibilities. He became a licensed and practicing lawyer in Hempstead. He was assistant principal at his older brother’s school. He was vestryman at St. George’s Hempstead. But he turned his eye to the family woodlands by the 1820s, deciding to build on his ancestor’s initial investment over a century prior. The decades long investment of time, effort and money would cause him to publicly, frequently refer to the “Minisink Patent” as the “Moneysink Patent.”

We are fortunate to have a classic (by Wm J. Clowes’ standards) voluminous set of remarks that total 31 large pages, written in small cursive, that detail his work from 1839 to 1846. This timeframe would have been when Caroline was one year old, through eight years old, and includes the death of his wife in 1840 and his third and infant daughter in 1841.

By his own estimation, William Clowes owned 12,000 to 15,000 acres in Orange and Sullivan Counties in the 1840s, the childhood period of Lydia and Caroline. He also owned a store in New York City that was meant to create demand for the upstate lumber he harvested from his property. The store’s sole inventory two items – a sofa headstead, and “The Indispensible,” a wash table and commode designed particularly for the poor. Click here to read about William selling two pieces of wooden furniture in Manhattan he had sought patents on, owning everything back in the woodlands including river ferry, machine shop, saw mill, woodlands.

William sometimes had traditional roles: Lawyer, Postmaster

William was a licensed, practicing lawyer in Hempstead, and then to some degree in Sullivan County. Several months after his wife’s death, he secured the name “Hartwood” and became postmaster, and influential role at the time.

William saw things others could not see

If his complex business model was not challenging enough, William was haunted by an overactive imagination.Apographeran numbers. Numerical patterns in the Bible that, if understood, can bridge the growing gap between evolving science and the Book of Revelations. Equally, a call for worldwide universal time with Jerusalem as the global centerpoint.

Return to Early Life Index VI. UNRAVELLING, RELOCATION, REBIRTHWhile the landscape surrounding the house in Forestburgh was beautiful, life for Elizabeth and her young daughters could not have been easy and she frequently writes that her husband William is away, sometimes for a fortnight at a time, leaving her, with her mother-in-law Hannah’s help, to manage day to day life. As her physical condition worsened her brother’s daughter Elizabeth “Betsy†Hart came to live with them, staying on after Elizabeth’s death to care for the children.

Elizabeth’s death marked a turning point, not only for her daughters, but for William. Other early settlers in the Forestburgh area expressed their opinion that the “brothers Clowes were not calculated to develop a wilderness country, and considered William  a harmless visionary. It is easy to image that Elizabeth tethered William to the ground and without her he struggled for the next 9 years trying to find a way to financially and emotionally care for his two remaining daughters. He continued to live in the area, renaming it Hartwood in honor of his wife’s family, and in 1841 he became the hamlet’s first postmaster. Financial difficulties and disputes over family property beset him from the beginning and family letters indicate that Lydia and Caroline were often sent to various relatives, sometimes for months at a time.

Gradually both the Hart and the Clowes families came to understand that William was not capable of caring for his daughters, much less himself. On June 9, 1847 Hannah Clowes died at the age of 82, presumably at the Hartwood home she shared with William, who was then totally on his own. Two months later on September 8th the process of identifying guardians for the young girls had begun. It would take another four years for their future to be settled with the girls often being shuttled from one family home to another. In a September 9, 1850 letter Elizabeth Hart tells her husband Benjamin that William has been turned out of his home and is asking for money. “How could I think of your dear sister’s children in such circumstances of want and do nothing for their relief.â€Â But William persisted in trying to keep his family together and it took yet another year until the eldest Hart sibling,  Rev. William Hart, convinced William that it would be best to send Lydia to his daughter’s home in Richmond and that Caroline should go to the Benjamin Hart family in LaGrange. While William had apparently agreed to this solution,  within three weeks he had concluded to sell a piece of property for $800 which he believed would enable him to keep his family all together. It was not to be and by November Lydia was on her way to Virginia and Caroline was at Heartsease where she would remain for the rest of her life. After a decade in which they had lost their mother and endured the chaos and disruption of never living in a stable household,  Lydia and Caroline were now safely tucked into warm and nurturing households where they could start the next chapters of their young lives.

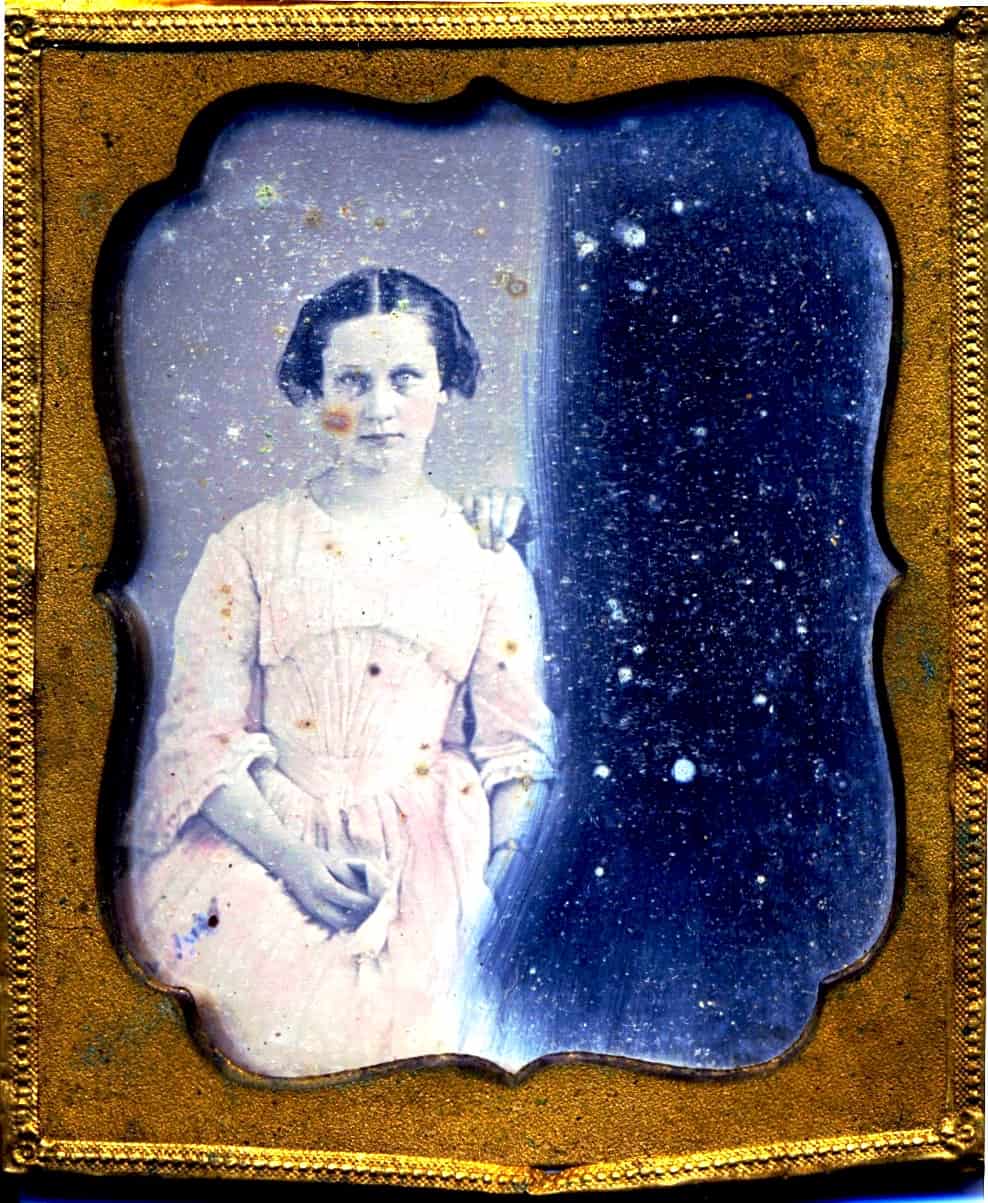

Caroline, undated daguerreotype.

Sister Lydia, undated daguerreotype.

Surrogate mother, Elizabeth Nichols Hart.