By Bill Jeffway

A version of this article appeared in the December 16, 2020 Northern and Southern Dutchess News / Beacon Free Press. See pdf at right:

Above: Newspaper clippings from the late 1940s show plans for a suspension bridge directly into Rhinebeck at Rhinecliff, and plans to turn the Taconic Parkway into a six-lane highway.

One way or another, within the bounds of Dutchess County, we all occasionally need to “get from point A to point B.” This has been true for European settlers over a few centuries, and for the Indigenous People over a few millennia. For most of that time, the goal was to find not necessarily the shortest route, but the flattest route. That changed with the evolution of the gasoline-powered “horseless” era. But the layers of preceding generations’ efforts to get from A to B, when a different environment offered different barriers, can still be seen.

The oldest example of evolving road use is what we call Route 9. The Indigenous People used a footpath that ran from the southern tip of Manhattan north past what is today Albany. The trail evolved from footpath, to horse trail, to wagon trail, to car and truck road, with a railroad growing up in parallel in the mid 19th century. It was declared the “Post Road” in 1669, taking on a formal role in mail delivery that remains among one of its many purposes today.

One of the reasons a parallel alternative to the river was needed was because as recently as a century ago, the Hudson River regularly froze every winter, barring travel on it for a quarter of the year. The big news would be estimating when the river would be blocked, and when it would reopen. Until the railroad started to break into Dutchess County in the 1850s, the only means of travel north/south in the winter was on the road.

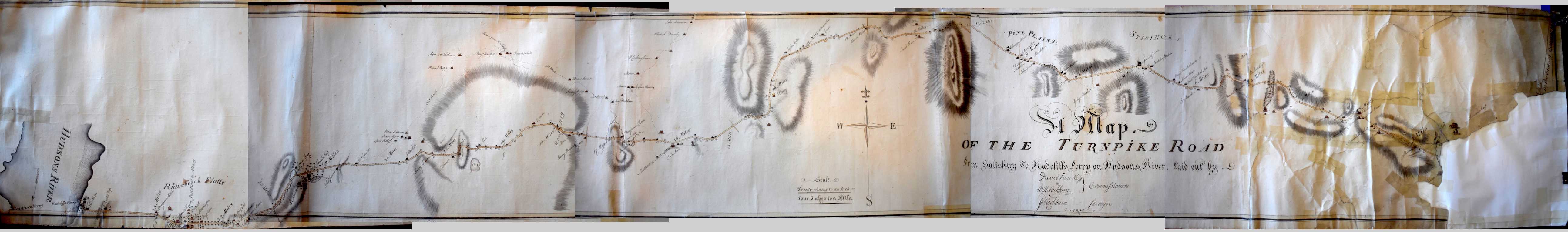

Above: The amazing 1802 Salisbury Turnpike map, carefully preserved by the County Clerk, and visible on the County Clerk office walls, is today known as Route 199 (with some exceptions). It is understood to have emerged from a footpath of the Indigenous People.

In terms of roads going east/west, the Dutch, and subsequently the English, claimed land rights 20 miles east of the Hudson River. Farms were established where soil was good and streams allowing water power for saw and grist mills were nearby. Just as settlement patterns were along the mighty Hudson River, so, too, settlement was around the smaller rivers, streams and creeks that flow into the Hudson. Industries like mining and furnaces for iron ore also emerged.

Unlike New England, where a central plan for a town, around a green where civic and religious buildings would be found, between the combination of the early Dutch settlement style, and Landlord and tenant farmer model, Dutchess County had a much more organic, and much less “templated” evolution of hamlets, villages and towns.

The points along the river became the exchange points for inland farmers to bring livestock and grains in exchange for manufactured goods. Three river towns emerged first. Rhinebeck, Poughkeepsie and Fishkill Landing (now Beacon) were each approximately15 miles, or a day’s ride from each other. Poughkeepsie, in the middle of the county along the river had Turnpikes radiate out like spokes in a wheel. The Salt Point Turnpike connected Clinton and points northeast (Route 115). The Dutchess Turnpike went due east (Route 44) but split into branches to Dover and Sharon, CT. The “Beekman and Pawlings Turnpike” was the southeast connection (Route 55). The northern part of the county, the top tier row of towns east of Red Hook, were the last to be settled. And Rhinebeck’s Turnpike connecting inland was the Salisbury Turnpike which as its name suggests, connected due east to the Salisbury, CT iron mines.

These were very early days for private roads and incorporation, and you will not be surprised to find that investors in the Turnpike owned land along its path. One of the directors of the Salisbury Turnpike, for example, was the owner of what is now the Beekman Arms in the center of Rhinebeck. He ensured that the terminus would involve travelers going past his hotel, and not in what might have been an easier route (avoiding a large hill) to terminate in Red Hook just to the north.

The shift from ferry to bridge for motorcars was the last big impetus for change. The first bridge in the county was built at Poughkeepsie in the early 1930s. The “spokes” around Poughkeepsie simply grew larger and larger until they are what we see today. The second bridge was to be built to the north. The original plan was to have suspension bridge, very similar in appearance to Poughkeepsie’s Mid-Hudson Bridge, connect Rhinebeck directly to downtown Kingston. Rhinebeck residents objected, and the bridge was instead built where it is today, four miles north. The different conditions required a truss bridge, rather than a suspension bridge to be built.

The east/west connection to the Kingston/Rhinecliff bridge, the creation of an enlargement of what is today Route 199, beautifully shows the impact of gasoline powered construction equipment and cars and trucks.

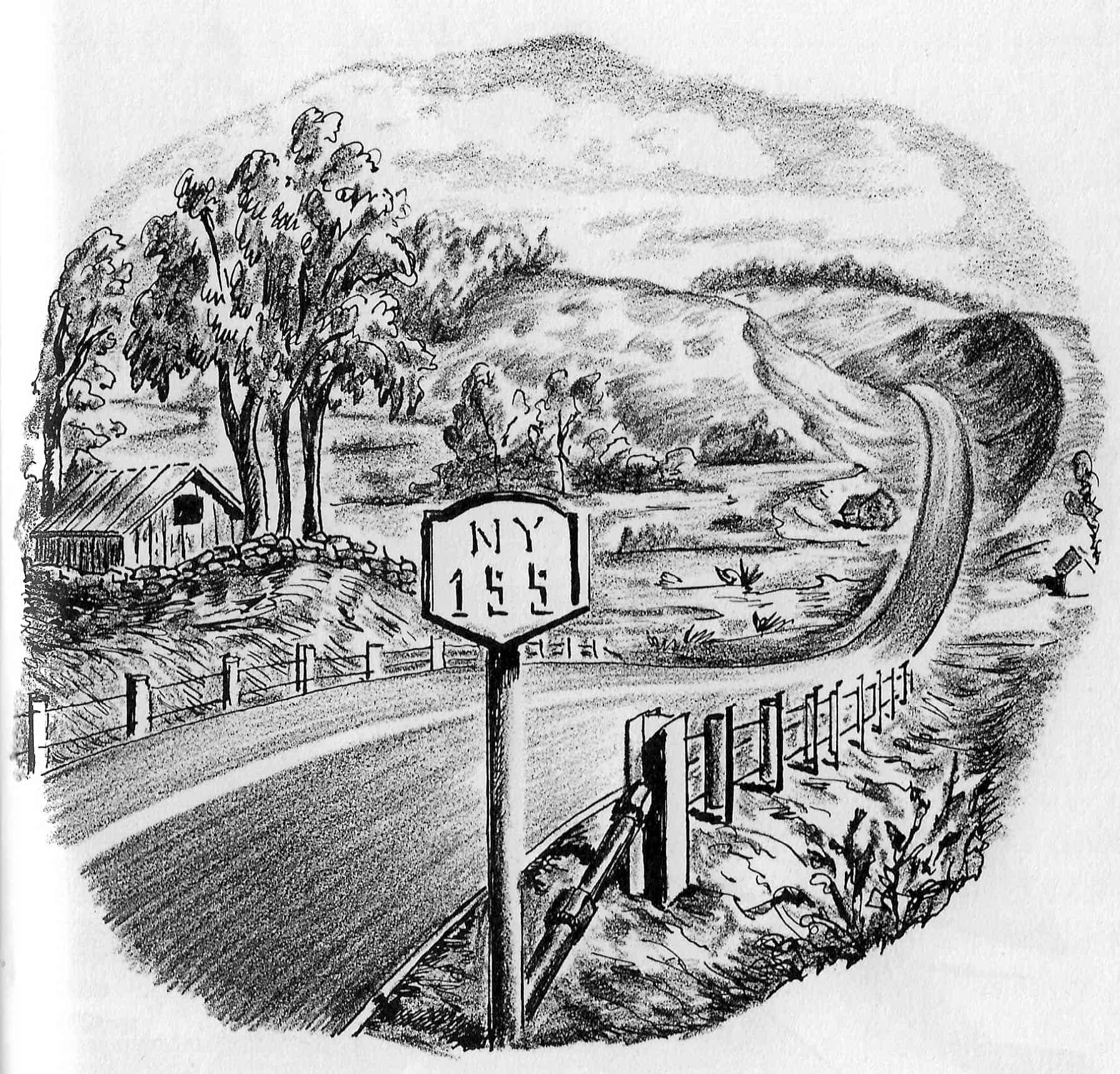

The nationally known artist, Milan’s Henry Billings, was known for his artistic talent (he was the WPA artist who painted the Wappinger Post Office murals under FDR’s watchful eye) and his interest in science and engineering. In the 1950s he published an illustrated book called, “Construction Ahead” where the history and evolution of road building is examined. He proudly illustrates a major straightening out of the new Route 199 a mile west of the Taconic Parkway, effectively creating an entirely new segment, with the big gouge created by the latest and most powerful construction vehicles.

Above: Milan artist Henry Billings, in a 1951 book celebrating gasoline-powered road construction equipment, depicts the achievement of creating a straight road through a deep gouge cut in hill in his hometown of Milan, a mile west of the Taconic Parkway.

Especially from such activities in this period, our county is replete with little roads that parallel our current larger county roads. You will find them everywhere. If a smaller road connects to a larger road at a very sharp angle, this is a good indication that the smaller road was once the main thoroughfare, more winding and shaped to the contours of the earth.

A quick look at Dutchess County Parcel Access reveals that some version of “Old Albany Post Road” can be found in Hyde Park, Poughkeepsie, Red Hook, Rhinebeck and Wappinger. And that about 1,908 households live on a road called “Old fill-in-the-blank Road.”

Of course the straightening and widening can go too far. The October 26, 1949 Kingston Daily Freeman announced State plans to use the path of the Taconic Parkway to build a north/south six-lane highway through Dutchess County. Imagine the different County we would have. That is the pattern on the east side of the Hudson River.

So as you crane your neck trying to emerge from a funny little road at a crazy angle to a big county road, or if you find it is hard to drive precisely east/west, rather than northeast/southwest or northwest/southeast, or if you are on a tiny road that is formally called a “Turnpike,” you will know that the contours of our roads have sprung from centuries if not millennia of prior patterns.

Above: One of the influences on the contours of our roads dates from the 18th century original division into land patents. At the top, a contemporary image from Dutchess County Parcel Access highlights the location of the hamlet of Lafayetteville in Milan and the center of the Town of Pine Plains. The pattern of some of the original 900-acre rectangular lots can be seen. This is highly speculative, but Augustus Graham, one of the nine partners who was granted lots, was granted two adjacent lots. His son Lewis Graham built a house in the northern lot, and his son Morris Graham built his house on the southern lot. The road that runs past them is the major north/south road at the center of Pine Plains.

Reminders of the horse…and horseless eras of travel on a dirt road near the Salisbury Turnpike in the Town of Milan.