This is the online version of a traditional exhibition called You are here! that was designed to be viewed onsite at Red Hook Village Hall, the geographic location of the original Hardscrabble, on September 18, 2021, Hardscrabble Day. References in the text that reflect the assumption that the viewer is in that location are preserved. You are here! is a collaboration among the Dutchess County Historical Society, the Red Hook Public Library, and the Village of Red Hook.

You Are Here! focuses on the history of the immediate area, or “four corners” of the Village of Red Hook. No one is quite sure why it was first called Hardscrabble in the late 1700s, a word suggesting poor soil, and tough work. Perhaps this is why the term went to quickly and completely out of use in the early 1800s. David Van Ness, whose Maizeland home still stands adjacent to the Red Hook Central School on West Market Street, started to name and operate the Red Hook Post Office out of this area and the original Red Hook hamlet, three miles north, was forevermore relegated to the relative position of Upper Red Hook.

A letter to the editor in the July 22, 1859 Red Hook Weekly Journal scolds the paper for not mentioning the original name of Hardscrabble in a recent historic profile, but then acknowledges, “Why this harsh name was applied to our beautiful village I have been unable to ascertain from tradition or historical sources.” So the origin of the story was lost by 1859.

This exhibition examines the intersection of the north/south and east/west roads that were central in establishing Red Hook’s purpose, identity and growth. We are introduced to the members of (and extant buildings related to) the Massonneau family, who were important business and civic leaders in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

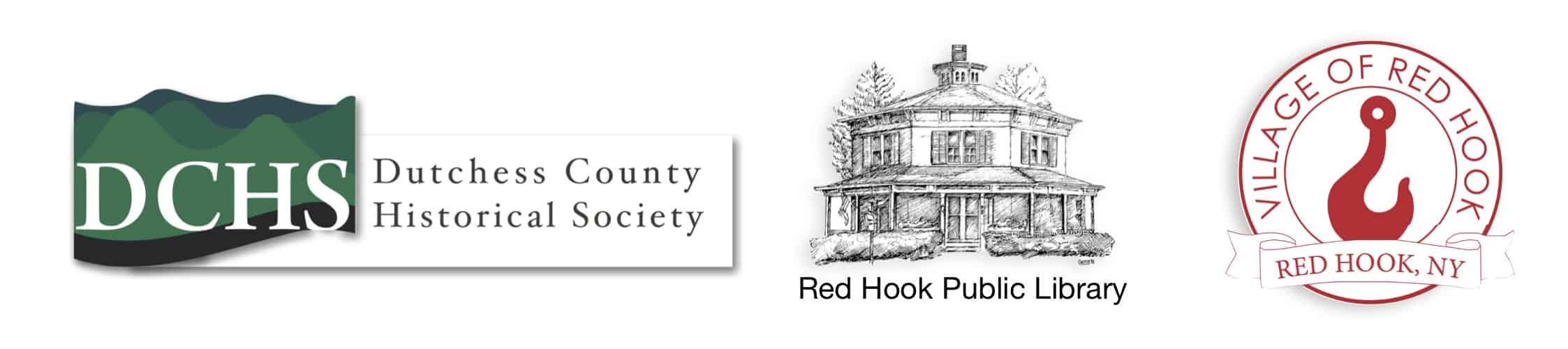

ABOVE: Maps of the vicinity over generations. Contemporary map shows the location of the three extant commercial buildings related to the Massonneau family.

North/South:

From Footpath to Highway

Several thousand years ago, the Indigenous Peoples living in this vicinity were more accurate in the name they gave the enormous waterway a few miles west of today’s Red Hook village. We incorrectly refer to it as a “river,” which by definition means that it would flow in one direction. But the Indigenous Peoples’ descriptive name, Muhheakantuck, referred to the alternating flow of the massive tidal estuary, put in motion by the moon’s gravitational pull. This dual directional force was particularly handy in the days before the 1807 invention of steamboats.

Red Hook sits roughly halfway between the massive waterway’s connection to the sea (New York City) and its connection to the east/west oriented Mohawk River (near Albany). This “in between” nature of the area was accelerated with the 1825 opening of the Erie Canal which amplified the Mohawk River so that canal boats could connect to Lake Erie at Buffalo.

Route 9, which had been known as the Albany Post Road (connecting Manhattan and Albany), and before that in colonial times known as the King’s Road, was originally a footpath created by Indigenous People. Until a century ago, the Hudson River froze for several months in the winter, giving preference to the path or road, another reason the road grew, and was maintained parallel to the river. By 1864, the railroad between New York City and Albany stopped at Barrytown and Tivoli.

The area that is today Red Hook approximates a border area between the Mahican, whose large civilization extended north from the area of the U-shaped Roeliff Jansen Kill (a stream that is the settlement area of today’s Columbia County) – and the Wappinger or Delaware, whose large civilization extended south from the area of the Y-shaped Wappinger Creek (a stream that is the settlement area of today’s Dutchess County).

ABOVE LEFT TO RIGHT: The area that is today Red Hook, was a kind of “in between” area separating the massive Mahican civilization northward, and Wappinger or Delaware southward.

Photo of a locally found point that is several thousand years old, with a contemporary assembly for demonstration purposes. From Deer Terrace exhibition. Courtesy of Bard College Archaeology Field School, Christopher Lindner, Director.

Images of the 1940s Rhinebeck Post Office murals by Olin Dows depicting the enslaved coachman of the family of Chancellor Robert Livingston. A newspaper ad from 1800 reflects the typical method that men, women and children were bought and sold as legal “property.” In 1790, Red Hook/Rhinebeck (one municipal unit at the time) had a population of 421 enslaved men, women and children and 66 “Free Persons of Color.” See the Red Hook Black History Trail.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, passed by this place on the Albany Post Road on the morning of May 23, 1791, on a tour of the Hudson Valley. Their coach was driven by Jefferson’s slave, James Hemmings, half-brother to the better known Sally Hemmings. They had left Poughkeepsie that morning, and spent the evening in Claverack, Columbia County.

A few days before Christmas in 1912, as a warm-up to the massive April 1913 march to Washington D.C. as a demonstration for women to gain the right to vote, General” Rosalie Jones passed by this place leading a parade of pilgrims from New York City to Albany to petition the Governor. They spent the night in Upper Red Hook. Women gained the right to vote in New York State in a 1917 referendum.

East/West: Connecting Rural Dutchess & The World

East/west travel saw farmers bringing their goods to be shipped either south to New York City or north to Albany. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 opened up markets, but also opened up competition. As a result, the area shifted away from growing wheat in the early 1800s, to operating apple and dairy farms after the railroad emerged and the tragedy of the Civil War was over. As refrigeration technology emerged, the apple and dairy business strengthened.

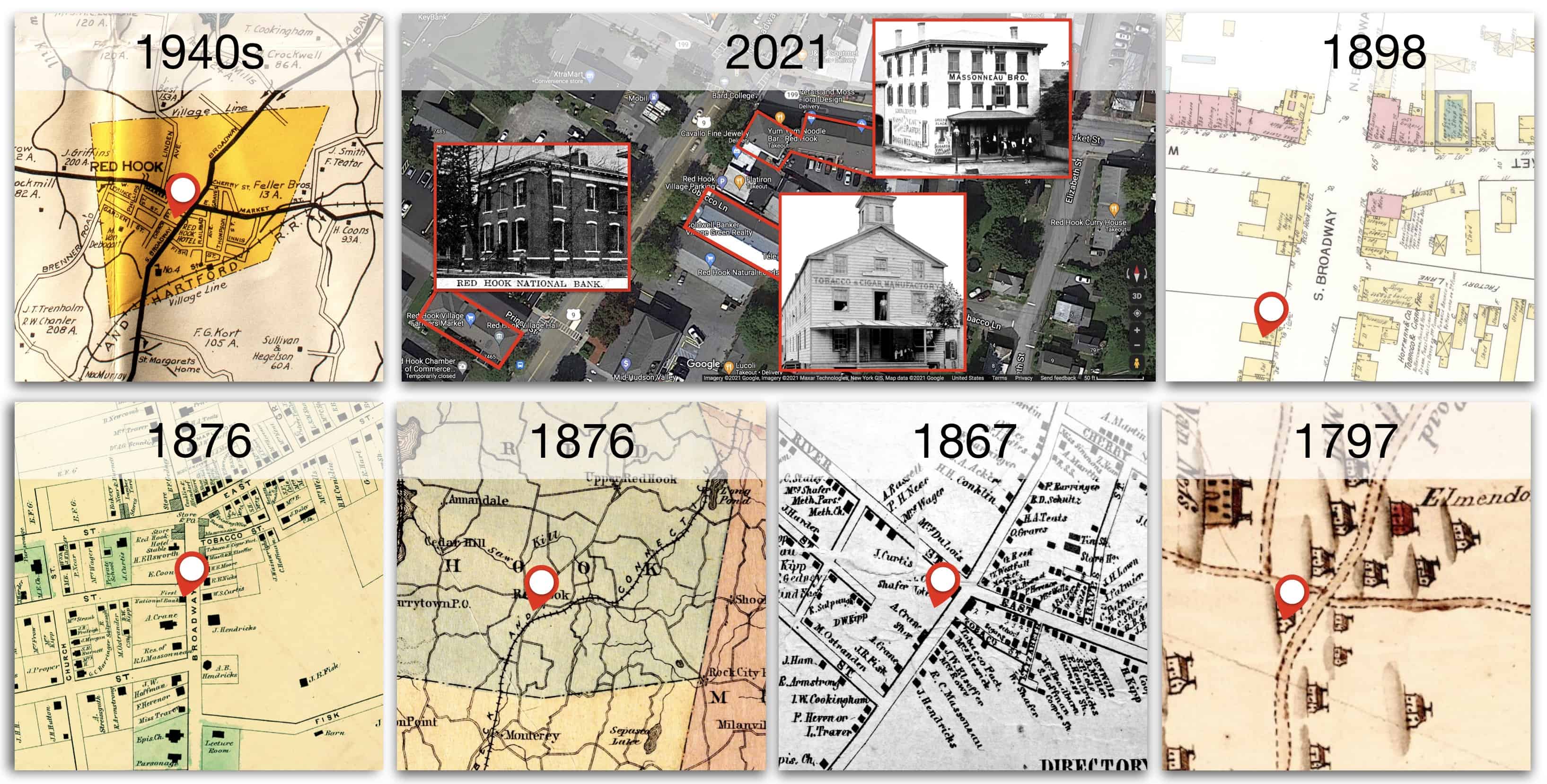

Another business supported by the east/west route was the mining of iron. Salisbury Connecticut had a particularly large mine, but smaller mines and furnaces dotted interior Dutchess County. A 1797 map shows that the landing due west of the Village four corners was called [John R.] Livingston’s Landing, also Lower Landing, and eventually Barrytown.

The east/west route was strengthened when Rhinebeck & Connecticut Railroad opened in 1875. The tracks ran from just south of the village to the building known today as the Chocolate factory.

Imported and manufactured goods came in returning boats to be purchased by local farmers and an emerging middle class. In early years, transactions involved the bartering of goods. By the late 19th century, cash emerged as the preferred payment method.

ABOVE LEFT TO RIGHT: The landing due west of the Village center was owned by a Livingston and was prominent and active during the Revolutionary War. Known as Lower Landing, it eventually came to be known as Barrytown.

Image of the one of the earliest farms held in freehold, the Fulton farm was purchased in the late 18th century. 19th and early 20th century photos courtesy of the Norton family. Images of iron mines at Salisbury, CT and Amenia.

Five Generations of Massonneau Family Influenced Red Hook Village

!Claudius Massonneau was born in France in 1769 and came to the newly formed United States with his twin brother, Pierre, when they were young adults. Settling in Red Hook, Claudius married a Livingston daughter and produced a son, Robert Claudius Massonneau (1797 to 1877). “R. C. Massonneau” became a civic and business leader with third, fourth, and for a short time, a fifth generation (this time a woman) having important civic or commercial roles.

3rd generation: Robert Livingston Massonneau (1825 to 1898). 4th generation: Robert Livingston Massonneau, Jr. (1860 to 1951) and William Strobel Massonneau (1862 to 1936) who was at one time Red Hook Village President and lived in the house that still stands at the north west corner of South Broadway and Fraleigh Street. 5th generation: William Massonneau’s teenage daughter, Elizabeth (no known photo) became the Secretary and Treasurer of the Red Hook Suffrage Workers organization in 1915. The organization seems to have been small and short lived, perhaps not functioning after the November 1915 referendum on suffrage failed. Elizabeth shortly thereafter married and moved to Rhinebeck. See Red Hook Suffrage Trail.

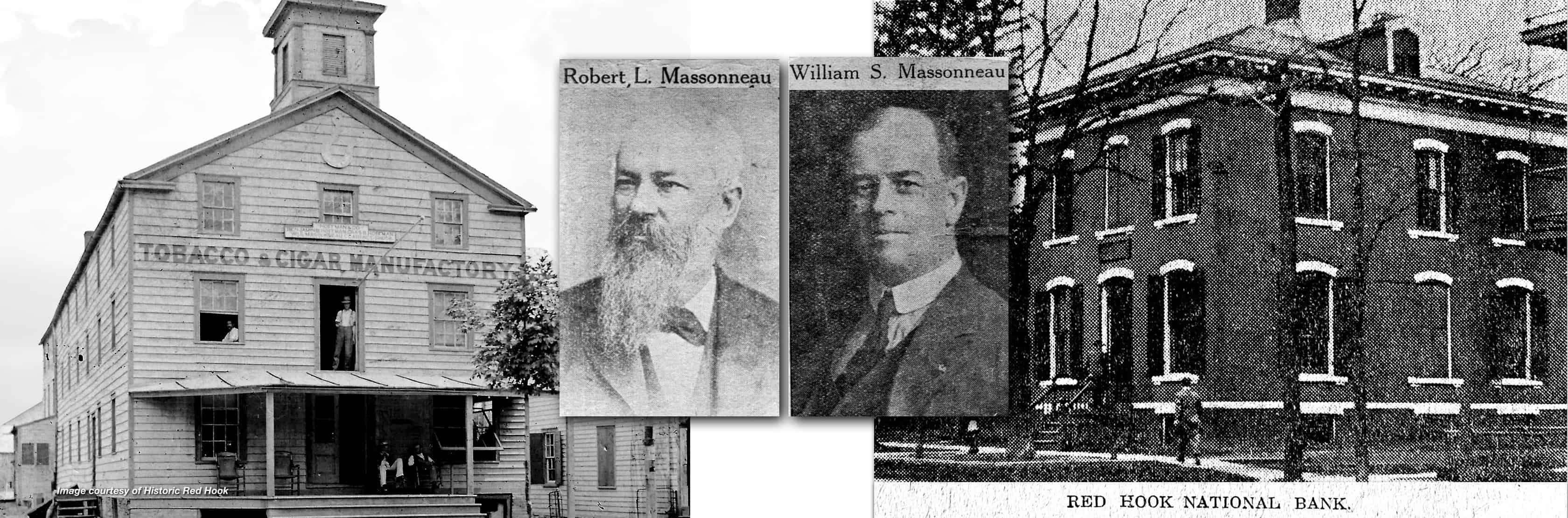

ABOVE LEFT TO RIGHT: The Massoneau family, and later the Hoffman family, were involved in the tobacco business. The building stands today. The Village of Red Hook Village Hall was formerly the Red Hook National Bank. The Massonneau family were among its earliest founders. Shown above is third generation Red Hook resident Robert Livingston Massonneau, and fourth generation William Strobel Massonneau.

The Massonneau Building

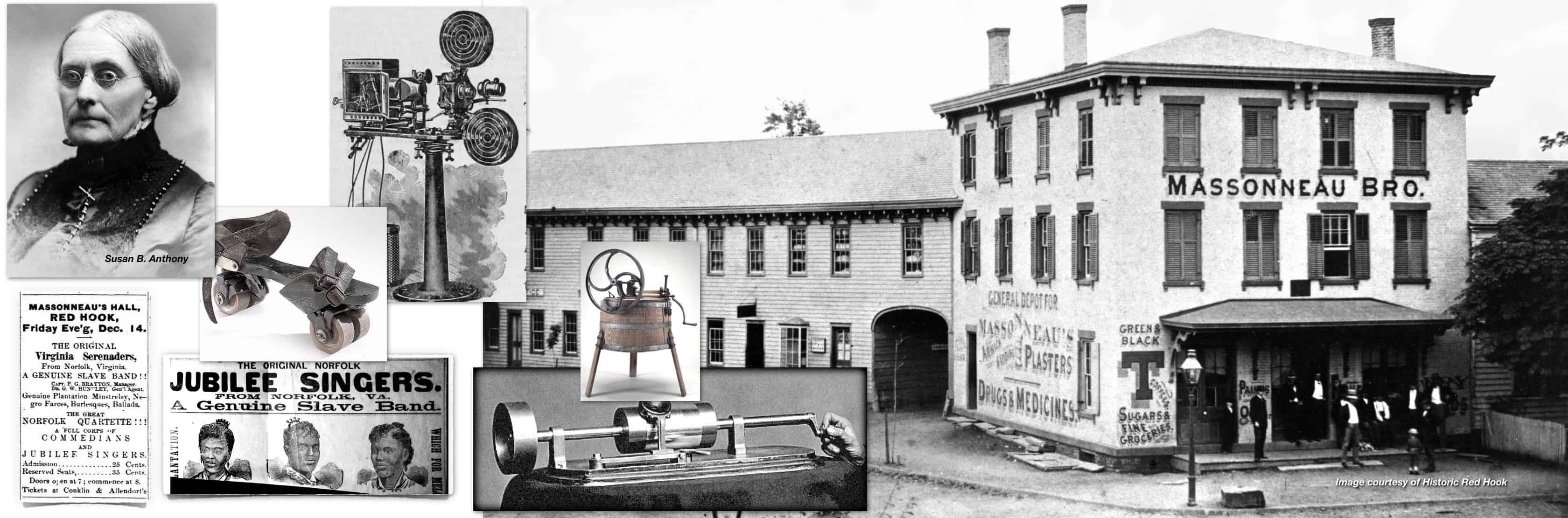

The brick, Italianate style Massonneau Building was built by Robert Claudius Massonneau around 1855. It served a wide variety of purposes!

Susan B. Anthony spoke there on January 1, 1879, after having spoken the day before, December 31, 1878 in Rhinebeck. The tireless, persistent voice of Susan B. Anthony rang out in the public hall in this building on an upper floor. Her talk, Woman Wants Bread, Not the Ballot, was a 90-minute speech she gave countless times between 1874 to 1889 across the country and in Europe. It would take 38 years from the time of her speech for women to gain the right to vote in New York State, through a November 1917 referendum.

Red Hook Village was created here in 1894. On Tuesday, July 17, 1894, in the ground floor, front room (where Yum Yum Noodles is located) registered voters (only men, 21 years and older) in a majority vote, voted to incorporate the Village of Red Hook.

1875 dancing lessons from Mr. M. R. Greene.1877 Virginia Serenaders & Jubilee Singers.

1879 Edison’s phonograph demonstrated.

1884 “Colored people’s” ball.

1890 Women’s Christian Temperance Union play, “A Drop Too Much.”

1895 Latest in washing machines displayed.

1896 Roller skating school opened.

1898 Public library opened.

1904 2nd floor fish restaurant.

1904 R. W. Chanler band and dancing.

1907 The Lost Prince by Red Hook Rokeby Estate’s John Jay Chapman.

1909 Moving Pictures, admission 10 cents.

Stretch Your Legs! Check Out:

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE

RETURN TO TOP OF PAGE