By Bill Jeffway, DCHS Executive Director

A version of this article appears in the Northern/Southern Dutchess News / Beacon Free Press edition of November 16.

The fact that the exhibition, Fertile Ground: the Hudson Valley Animal Paintings of Caroline Clowes, is taking place at Poughkeepsie’s Locust Grove, the former home of Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872), the inventor of the telegraph and Morse code, might at face value seem to involve the story of two persons in very different spheres. Although both are local, one is a woman of art. The other is a man of science.

But the historian Allan Nevins writes in a biography of Morse called The American Leonardo, “Had [Morse] never touched a piece of mechanism, he would be remembered as an eminent portrait-painter and the founder of the National Academy of Design.”

There is a wonderful symmetry and coincidence to the fact that Clowes was born on March 3, 1838, two months after Morse conducted his first public presentation of the telegraph having just put down canvas and brushes for good.

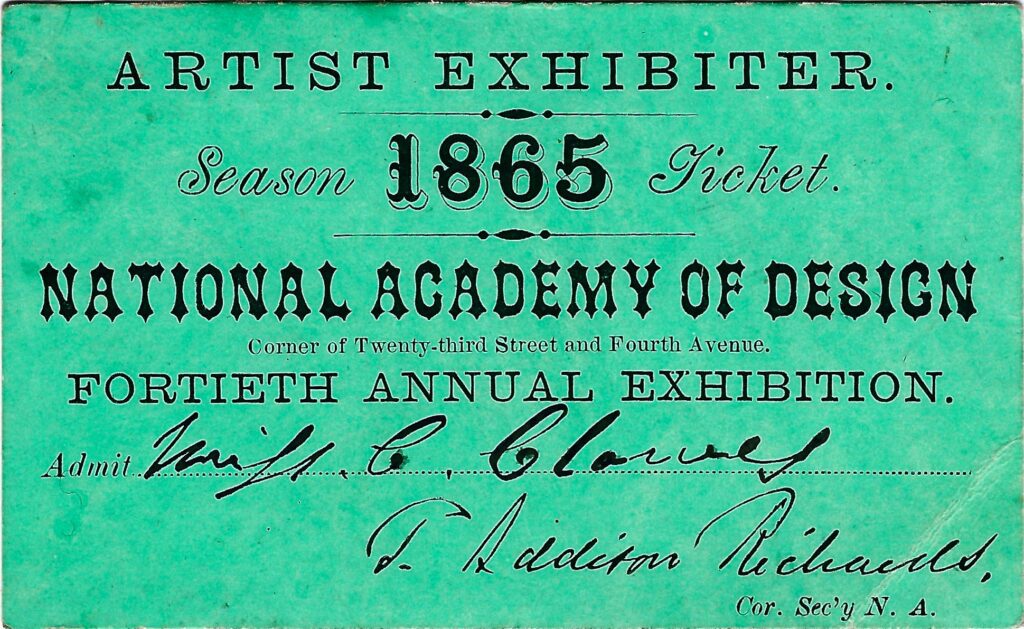

Clowes (1838-1904) was a full generation younger than Morse. She benefited tremendously from the National Academy of Design, which was founded in 1826, led by Morse as president until 1845, and remains active today.

The exhibition of Clowes’s work at the Academy started in 1865 and was facilitated by her private teacher Frederick Rondel. This was a watershed moment that quickly raised her profile nationally. The Academy was a formal place of learning, and a way for Clowes to connect with collectors and other artists.

In addition, Clowes benefited from the changes in the field of art that the Academy had brought about. Unlike Morse, who trained in Europe as any serious artist would at the time, Clowes did not go to Europe, nor did she need to. Given that a central goal of the Academy was to create a truly American style of art, certainly Clowes’s elaboration on the uniquely American Hudson River School style, shows that Morse and Clowes had a shared vision on this fundamental concept.

While studying religion, philosophy, mathematics and science at Yale, Morse earned money by painting portraits on the side. He settled in London and was accepted into the prestigious Royal Academy. His better-known portraits include John Adams, James Monroe, and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Morse preferred to paint earnest historical paintings that could educate the public; but his works of that type were not well received. Among the better-known examples of this type is his 1822 House of Representatives, a seven by eleven-foot painting of the interior of the chamber carefully depicting specific individuals. His 1833 Gallery of the Louvre is a six by nine-foot oil on canvas that accurately depicts 38 paintings such as da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Both failed to gain attention or result in any income for Morse. As a result, he had to rely on portrait painting for income. His painting career collapsed when he was turned down for a commission to paint a historical painting for the US Capitol building in 1837.

Even with his brushes and canvas firmly left behind in December of 1837, Morse maintained an artistic eye for the rest of his life. In a trip to Paris in 1839, he met Louis Daguerre, the inventor of the daguerreotype which was the early photographic process that created and reflected enormous detail, albeit in a somewhat other-worldly hazy glass, rather than paper. Morse was attracted to the idea as an aid to painting portraits. Rather than seeing this emerging technology as a threat to art as many did at the time, he thought it could be useful. He is credited with the earliest experiments with the daguerreotype in the United States.

From the proceeds of his inventing the telegraph, Morse bought the Locust Grove estate in 1847, and started a process of remodeling (see photograph) and became a visible member of Poughkeepsie society.

DCHS founder and photographer Margaret DeMott Brown took this photograph of Locust Grove Estate in 1932, which was published in that year’s DCHS Yearbook. An article about the location was written by Helen Wilkinson Reynolds, a personal recollection of Miss Leila Livingston Morse, granddaughter of Samuel F. B. Morse who was born at Locust Grove, was also published.

In August of 1855, Morse stopped in the photo studio of Samuel Walker, which was located on Garden Street, a short distance north of Main Street. Samuel L. Walker was one of the country’s most highly regarded and accomplished daguerrists. Walker married a Poughkeepsie woman and together they raised their children in a home that was also on Garden Street.

Walker reports in an advertisement published in the local newspaper in 1855, that Morse looked at his daguerreotypes and declared that if Walker had entered a recent contest for the best daguerreotype, where Morse was a judge, Walker would have won the top prize of a silver pitcher. Walker claims that he did not know about the contest, despite it being published through the leading national photographic journal at the time. In any case, what is revealed here is that Morse was playing an important role in national conversations about early photography in 1855.

Morse was named a Trustee by Matthew Vassar in the January 1861 founding documents of what was initially called the Vassar Female College. The role was far from ceremonial. Much work needed to be done to establish the College to the standards Vassar expected in a society exhausted by the Civil War, and suspicious of risks that would come with the higher education of women.

Arguably Morse’s greatest impact was through his being one of five men on the Arts committee, who were charged with establishing the first of its kind for an American college or university: an art department to teach students, and a gallery and collection of art of its own. The committee succeeded in bringing in Henry Van Ingen, the Dutch artist who was teaching in Rochester at the time, to lead the initiatives in art.

Van Ingen quickly became a friend and collaborator with Clowes. Letters show that he regularly brought students to Clowes’s home and studio in LaGrange.

Morse died in 1872, but we find connections between Clowes and Morse’s widow, Sarah Griswold Morse. Caroline Clowes was on a committee of five who created the inaugural art exhibition at the newly opened Vassar Brothers Institute on Vassar Street. The building stands today among the buildings of the Cunneen-Hackett Center.

Mrs. Morse ensured that Samuel F.B. Morse was well represented. A painting by Morse, called “St Francis,” was exhibited. A portrait of Morse by George A. Baker, and a statuette of Morse by an unspecified artist, were featured. Two paintings from the Morse family collection, one by F. Hiddlden and one by Oswald Achenbach, were loaned.

The weaving of Morse’s artistic and scientific careers is beautifully revealed when we learn that the major exhibition of his paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 1932, was prompted by the 100th anniversary of his 1832 trip on a ship from France to New York where he conceived of the idea of the telegraph.

Generally speaking, when federal censuses are taken every ten years, the occupation of the counted person is provided, as stated, by the person being counted. We find that in the 1850 federal census taken in Poughkeepsie, Samuel Morse said his occupation was “historical painter.” Being a historical painter was, of course, his very early dream, a dream he very quickly came to find was not working out for him. Perhaps he was stating an aspiration that remained buried deep inside him. If he had said “portrait painter” we could understand why, given his success in this field.

Like every good historical investigation, we do not get final answers, but instead get better questions. You are invited to see the paintings of Caroline Clowes at Locust Grove Estate, South Road, Poughkeepsie through December 30, Wednesday to Sunday, 1 pm to 5 pm, except Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day. The permanent exhibition of the works of Samuel Morse can be seen any Saturday or Sunday in that timeframe if you would like to see both. Both are free of charge.

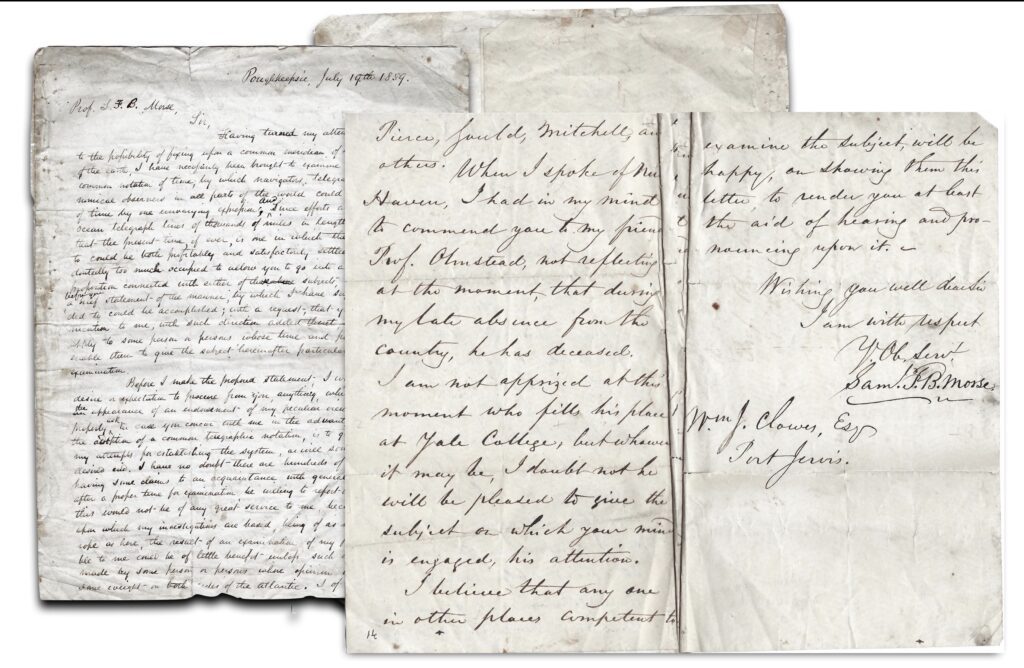

Right: Caroline Clowes’s father, very likely without her knowing about it, wrote to Samuel Morse in 1859 looking for comments on his ideas about instituting a global, universal time. Morse was polite, but advised that he was not the best person to consult on the matter. Morse wrote that he should contact persons better suited to the matter, like Maria Mitchell, the personal friend of Caroline Clowes.