We use such balms as have no strife,

With Nature nor the Laws of Life;

With blood our hands we never stain,

Nor poison men to ease their pain.

The Poughkeepsie Thomsonian [1842]

Now mostly forgotten, this motto once represented one of the most prominent health crazes of the 19th century. The poem advertised the Thomsonian (or “Botanic”) system of medicine in which doctors challenged conventional medical practice, instead recommending natural plant-based cures. While largely ineffective, these remedies captivated public attention, something we are all too familiar with in an age of health influencers and digital cures. Dutchess County, particularly Poughkeepsie, had a strong voice in the Thomsonian movement. This philosophy created a vibrant sub-culture within the County’s medical community for more than two decades, receiving state and national attention.

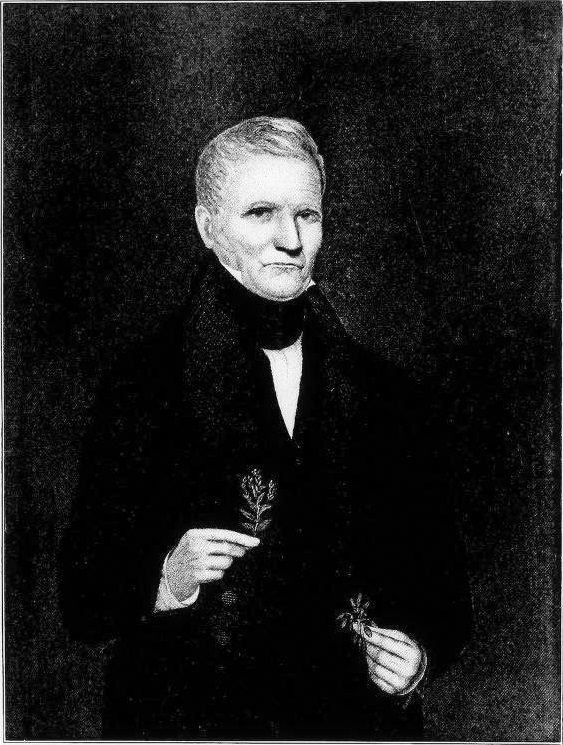

Dr. Samuel Thomson (1769-1843), the movements founder, worked as an herbalist and botanist in rural New Hampshire. In the summer of 1790, Thomson’s wife Susanna suffered a life-threatening illness that conventional medicine was unable to cure. Turing to a plant-based remedy, Susanna eventually recovered. The following decades, Thomson developed his new medical system, testing various cures on his neighbors and children. In 1822 he released the New Guide to Health, or, Botanic Family Physician, which outlined natural remedies to common alignments.

Above: Portrait of Dr. Samuel Thomson, Founder of the Botanical Health Movement. The image appears in the 1835 edition of his New Guide to Health.

Thomson and his followers cultivated a personal system of bodily health in which medicine targeted the root of the problem rather than treat its symptoms. These “cures” ranged from specific activities such as the famous Thomsonian steam bath in which a patient drank a mix of cayenne pepper and laxatives while sitting in a sauna, to common herbal medicines. Ardent Thomsonianists publicly denounced doctors who practiced blood-letting and used harmful or toxic drugs such as Opium, Laudanum, and the mercury solution Calomel.

These cures purported to solve illness without invasive procedures. Through natural substances—only compounds easily derived from plants—they promoted a holistic view of the human body, targeting both physical and emotional unwellness. The historic News Paper Collection in the Dutchess County Historical Society’s archive, replete with signs of this system, shows the range of these Thomsonian remedies. One notice, included in an 1836 issue of Poughkeepsie Journal advertised “syrup of Liverwort,” “Cephalic Snuff,” and “Concentrated Syrup of Sarsaparilla” all made in Thomsonian fashion with “medicinal herbs, extracts, and ointments.” Another, published in an 1841 issue of the Poughkeepsie Telegraph, claimed that all-natural vegetable pills sold in every town in Dutchess would cure any fever, “Bilious Cholic, Dypensia, heart burn, and Female Weakness.” These local examples aptly demonstrates both the range of uses and the variety of material claimed by the Thomsonianist.

Through cures like this, the movement attempted to empower individual health. Under the Thomsonian system, patients had full control over the administration of treatments. Informally trained practitioners and local Thomsonian publications could recommend cures that could be purchased at Thomsonian stores, but nothing was prescribed. Thus, easily applied and widely applicable cures had the greatest appeal.

The movement grew as stories of miraculous cures spread throughout the county. Outside of New England, New York had the largest community of Thomsonianists, and Poughkeepsie functioned as a locus for the state’s Thomsonian movement during its formative years. Indeed, as the Poughkeepsie Eagle noted in 1837, the city was quickly becoming the meeting place of Thomsonian medical conferences and the State’s Thomsonian Medical Society.

The most prominent local Thomsonian was Thomas Lapham (b. c.1780). Lapham ran a clinic, store, and school for the new systems treatments on the North end Catherine Street in Poughkeepsie. In May of 1838 Lapham along with local businessman A. H. Platt printed the inaugural issue of the Poughkeepsie Thomsonian a bi-monthly newspaper that detailed, remedies, clinics, and testimonies. Each issue of the Poughkeepsie Thomsonian offered to “Let a knowledge of the healing art be diffused among the people,” a nod to the broader movement’s desire to make medical knowledge public. The publication’s readership rapidly expanded, distributing thousands of papers, reflecting the movement’s success in the county with dozens of practicing offices and several Thomsonian societies.

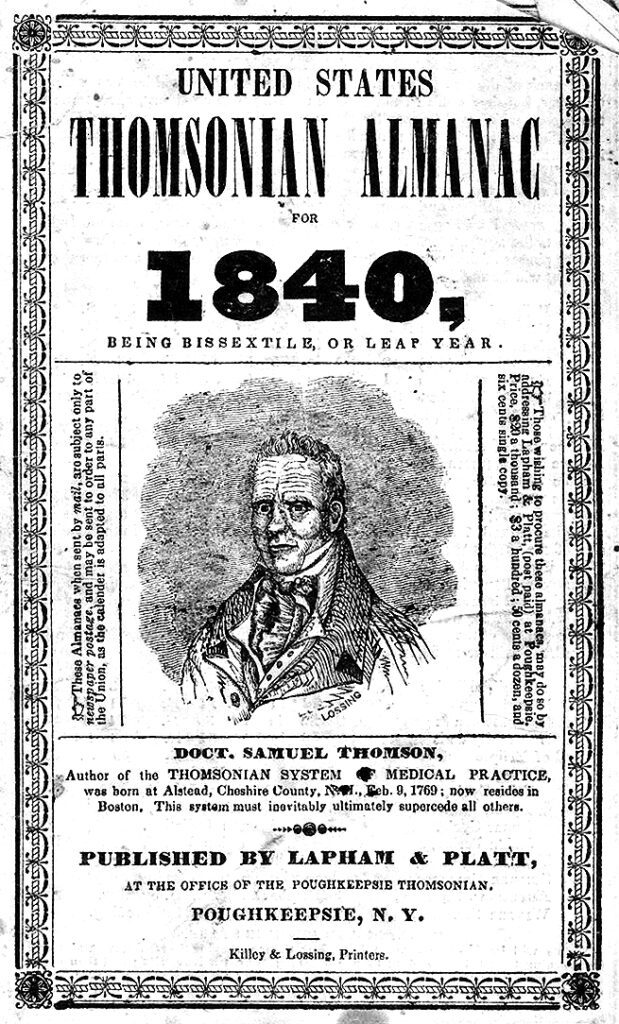

The zenith of Dutchess Thomsoniansm can be seen in medical publications where the Thomsonians of Dutchess County gain national attention. In 1840, the editors of the Poughkeepsie Thomsonian—facing harsh criticism over the validity of the medical system—called for the creation of an informative almanac. Originally used as a tool to chart stellar movements and weather, by the 19th century almanacs were full of informative articles that often looked at personal health, farming, and history. Their reputation for credibility made them the most popular serial publication after newspapers.

Lapham and Platt called for a national publication based in Poughkeepsie titled the United States Thomsonian Almanac (or Poughkeepsie Thomsonian Almanac). In his appeal, Lapham described almanacs as “powerful auxiliaries [for] advancing the Thomsonian system.” During a meeting of notable practitioners later that year Poughkeepsie’s request was accepted. While several other communities already had established and successful almanacs, Thomsonianists in Poughkeepsie distinguished their book by adding several new cures that existed outside of Thomson’s system. They even provided a detailed history of several. In doing this, they promoted unapproved herbs which they claimed better regulated the body’s blood and had a wider historical use.

The movement’s founder declared the United States Thomsonian Almanac dangerous, claiming the additions would harm any who used them and had no place in the medical system. However, the damage had already been done as Lapham and Platt shipped thousands of copies throughout New York and the country. Amongst practicing Thomsonists the book received high praise. The Botanico-Medical Recorder in Cincinnati, Ohio deemed it “admirably well calculated” and called for all Thomsonians in the West to “exert himself to circulate this almanac.”

Despite its success, issues with nonconformity prevented further publications of the almanac. However, Poughkeepsie Thomsonian continued to publish, and by 1848 the publication moved upstate to widen its reach, changing names to the New York Thomsonian. While this popular medical movement was not unique to Dutchess County, the enthusiastic involvement of many of its residents left a mark. This history continues to crucial insight to better shape our understanding of the politics and health movements in our county. As we consider what constitutes legitimate medical knowledge, we should be aware of the parallel between this history an our own day.