Navigating Wealth & Poverty: the Varied Economies of the 19th Century Black Community

Bill Jeffway serves on the research committee of Poughkeepsie-based Celebrating the African Spirit, as well as on the external advisory committee of Vassar College’s Inclusive History Initiative. Jeffway has been DCHS Executive Director since 2017.

Click “Watch on YouTube” to access full screen view:

This article ran in advance of the program in the Northern/Southern Dutchess News as a program overview.

From its inception, the Dutchess County economy has been at the crossroads of great economic currents. From the earliest times of Dutch settlement it has operated in the economic realms of global trade right down to the smallest economic unit of the self-sufficient farm. We examine how the Black community, focusing on the 19th century in particular, engaged in all those economic levels locally. We find extremes of wealth and poverty, and a growing middle class of professionals who often worked within, or intersected with, these various levels of economic activity. Likely because of the pervasiveness of slavery even in the most rural parts of the county until its abolition in New York State in 1827, communities of color were present in both built up and the most remote in-land rural areas.

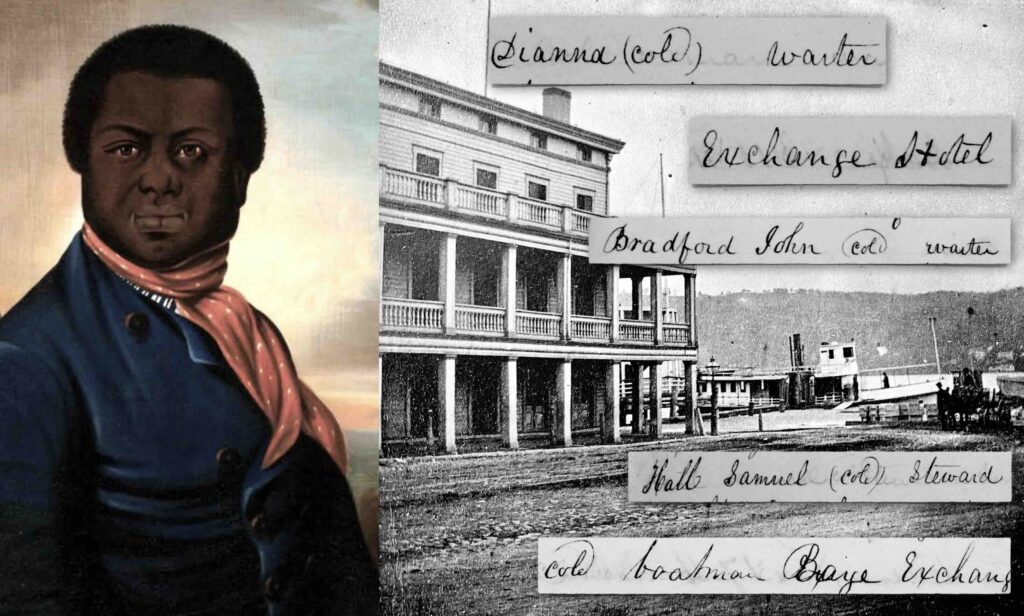

Paul Cuffee (1769–1817) Global Whaling & Trading Captain

We profile Paul Cuffee who was as a leading Captain of a global whaling vessel who happened to be Black and who had an entirely Black crew. Based from New Bedford, he would go on whaling trips that might take two or three years and involve navigation around the world. Like many successful Black entrepreneurs, he was involved in developing ideas to address racial justice issues, as well as whaling and trading of cargo for business income.

It is this trading in cargo that specifically engaged him with Poughkeepsie at the end of the War of 1812 with Britain. Abram Lincoln Harris wrote about Cuffee in his landmark 1936 book, The Negro Capitalist, explaining that among Cuffee’s cargo in 1815 was African camwood which he sold at Poughkeepsie. Camwood was a very popular item, which when ground, could provide a deep red, or reddish brown color that was very popular.

The United States had not yet moved to the mass manufacturing of clothing. Individuals still bought different color dyes for use at home, although industrial-scale demand was very much growing locally at the time. An advertisement in the Poughkeepsie Eagle of 1815 for Barnes & WIlloughby, a general store, offers “camwood” for sale among other dyes. Camwood is made from the heartwood of baphia natida, a small evergreen tree or bush native to West Africa that is a deep, warm red or reddish brown. We don’t know what he paid for the Camwood in Africa, but Harris reports Cuffee sold it in Poughkeepsie at $100 per ton.

Jeremiah G. Hamilton (1806–1875) America’s first Black Millionaire

A generation later, just before the Civil War, Jeremiah G. Hamilton was described as” the only Black millionaire in New York.” The term “robber baron” described the aggressive tactics and nature of the emerging newly wealthy, like the Vanderbilts, and Hamilton fit that mold and reputation as well!

Hamilton’s embrace of Poughkeepsie was not just a place of investment, but a potential place to reside. What caught his attention was what remains the single biggest blueprint for growth for Poughkeepsie: plans through The Improvement Party. The group consisted of local wealthy men like Matthew Vassar, who tapped into investors in New York City, likeJames Delafield, for whom Delafield Avenue is named in Poughkeepsie, and Hamilton.

In 1836 Hamilton invested in three things in particular that the Party proposed. One was the silk mill at Upper Landing, where he became a shareholder. Another was the purchase of Union Landing, a 400-foot-long dock, including three large storehouses, as well as a nearby five acres of land at the foot of Union Street at the Hudson River. And the third, perhaps the most visible, was his purchase of land and a significant house built in the grand Greek Revival style on Mansion Square, an area being developed by the Improvement Party.

The timing could not have been worse. By the spring of 1837 the national financial crisis derailed those plans, and the plans of virtually everyone who had invested in anything at the time. Recovery was years off and Hamilton went bankrupt, like many others.

On the Other End of the Spectrum: Getting By

DCHS Collections holds the writings of Thomas Sweet Lossing, who wrote in the 1930s about his childhood memories in Dover in the 1870s and 1880s. Among many topics he writes about is the significant Black community which provides uniquely detailed insights. He was the son of the noted historian of Dover, Benson J. Lossing.

“Their occupation mostly consisted of selling wild berries and making all kinds of splint baskets which they sold to the farmers of the surrounding countryside. It was said of Jackie [Duncan] that he could make a watertight basket. Amos [Duncan] would often come to our place with all sized baskets and usually succeeded in making a sale of some description as we use a great many. There always had to be a replenishment of bushel baskets for corn husking, and half-bushel baskets for apple picking, and a basket about 6 inches wide and 14 inches long which we painted red for our mother’s garden basket. One other basket we always had to be sure of having that was my mother’s key basket. This was a basket about 6 inches square and about 4 in deep with a strong handle. It was painted black and varnished with a little yellow stripe up under the rim to match the furniture in her bedroom.”

We know of other basket makers at the time, like Milan’s Jacob Lyle before the Civil War. And we will examine a host of other such activities.

The Bulk of Economic Activity: A Burgeoning Middle Class

A growing part of the population worked in a burgeoning middle class that included the better known trades of barbers, tailors, gardeners and domestics. The descriptor “gardener” may understate the roles of someone like Alexander Gilson, who was head gardener at Montgomery Place at Red Hook. He bred a unique double-blossoming Begonia which has the official Latin name of Begonia Gilsonia.

Blacks’ growing political influence affected job prospects and economics. The Bolin family is well known for this, but there are other examples. William K. Mowers of Amenia ended up working (and suffering a fatal heart attack in the office of) the US Secretary of the Treasury in Washington DC. A woman’s seamstress business came to employ others, including White women. Property ownership, and work in education and Churches were among the stepping stones used for multi-generational economic advancement.

Above: Paul Cuffee (1769 – 1817) was a world-famous whaling captain who sailed around the world and used the port of Poughkeepsie to sell cargo such as a rare African wood used for color dying. In the 19th century there was a large Black population involved in the river industry from riverboat captains and crew to stevedores. The image shows the Exchange Hotel at the foot of Main Street while the insets show a notebook used in the 1840s to collect census data showing Blacks at that hotel working as waiters and stewards. Photo and ledger DCHS Collections.

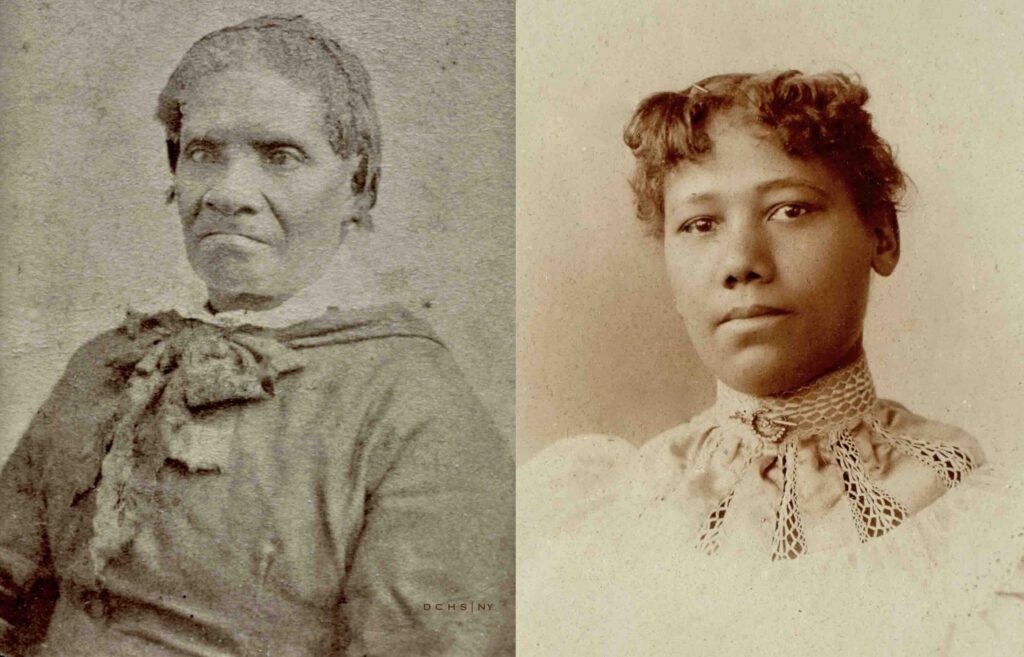

Above: Unknown individuals from the 19th century family album of Alma and Henry Jackson of the Town of Milan. DCHS Image Collections, gift of Walter M. Patrice. Patrice was the great-grandson of the Jacksons. An analysis of the clothing of those in the local family album suggests a range of economic status, worn with equal pride and care.