20th century

The Knights of Dutchess County

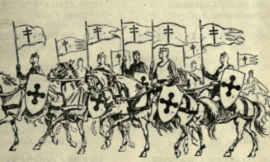

Each June marks the end of another academic year, and students throughout Dutchess County celebrate advancements in their education. A display of pins donated to the Dutchess County Historical Society by Marjorie Mangold in honor of her late husband reminds us that just over a century ago thousands of students shared this excitement through a unique end-of-the-year ceremony: investitures of Health Knighthood. The pins in the Mangold Collection, brought together by Harold Mangold Sr. and Jr. depict intriguing scenes of knights charging into battle or fighting dragons. On the border of each rests the phrase “Modern Health Crusade.” Once proudly worn by student “Crusaders” throughout the county, these pins speak to a complex history of children’s health education. The Modern Health Crusade (MHC) was a youth health education curriculum that began in 1915 to combat the spread of tuberculosis. The program lasted into the early 1930s and was taught in schools across the nation, Europe, and Asia. The Crusade succeeded in America during WWI, with one million students enrolled by 1919. Its popularity grew in the post-war period, climbing to well over three million active participants by 1923. First developed by National Tuberculosis Association (NTA), the HMC sought to cultivate hygienic and moral values. These values, deem by the HMC “health knighthood” or “health chivalry,” intended to mold children into good citizens able contribute to wartime preparedness. The movement’s founder Charles Mills deForest (1878-1947) called this the “Crusade Method of Health Training.” Above Left: Knight Pin; Depicts King Arthur knighting a Health Crusader with Camelot in background. Above is the National Tuberculosis Associations cross, a “K” for “Knight,” and a Health Cross. Above right: Squire Pin; Shows a horse and squire bearing a shield with the cross of the National Tuberculosis Association. Health Cross floats above. DeForest spent his career campaigning for children’s health education; he served as a field secretary for the American Red Cross Seals Division and the NTA. Throughout his work, he regularly noted that children struggled to adapt hygienic practices. DeForest posited that “good health” depended on students’ self-motivation. Therefore, he envisioned a curriculum that appeared as “fantasy game” which engaged children from kindergarten to 8th grade, charting their progress each term. In no less than four years, students moved through different knightly ranks. Beginning as a squire, a student became a Knight, then a Knight Banneret, and finally a Knight Banneret Constant. Advancement could only be obtained throughout the school year by the completion of “Crusade Chores.” These tasks, listed on a proscribed chart, ranged from hygienic activities such as “I washed my hands before each meal” to more aesthetic ones such as maintaining trimmed nails or hair. Each day the program required parents and teachers to sign off that the child had done these duties. “Chivalrous” students completed seventy-two chores a week, and after a year of living “chivalrously,” they were awarded the next rank. While deForest’s program was rigorous, he truly expected children to enjoy participating. In an article defending his methodology, he noted that, “Every child likes to play… He likes to play that he is grown, and to do something worthy of a grown-up.” Through play, the program reinforced “good health” with a tangible system of growth. “Health chivalry” sought to foster play through material rewards and competitions. This emphasis on recreation distinguished the program’s curriculum from other educational systems at the time. It attempted to alter methods of teaching rather than the information taught. A manual for teachers and nurses published by the NTA outlined how to include fantasy stories, songs, and crusade pageants. These elements culminated in the knighting ceremony, during which successful students moved to subsequent ranks. Dressed in handmade crusading outfits, students would gather singing Health Crusader songs as the teacher knighted students. During these celebrations, pins—like those in DCHS’s collection—were attached to the knight and to be worn during the following school year. Left: 1920 Knight Banneret Pin; Image of a mounted knight, holding the standard of the knight banneret with the letters “K” and “B” on either side of the Health Cross, the horse bears the National Tuberculosis Cross on flank. This appeal to competition was expressed in the schools and communities. The pins intentionally served as a physical sign of students’ position over their peers. As the NTA outlined, this disparity created a “visible daily reminder” of individual accomplishment which should motivate the student body to work harder. The MHC also granted students the opportunity to compete directly in national and inter-city tournaments. Schools in Beacon, Hyde Park, and Rhinebeck were the first in the nation to sign up to participate in the 1919 inaugural National Health Crusade Tournament where students participated in health and physical fitness drills. No Dutchess County school won the coveted pendant that year, but they continued to compete in the following tournaments. Indeed, the Health Crusade found a particularly strong voice in Dutchess County. An article a November 1919 issue of the Miscellany News—Vassar College’s student-run newspaper—noted that on the 25th of October, students from public and private schools in Poughkeepsie met at the Liberty Theater to watch a showing of the “Modern Health Crusade” movie. The children were so stirred by the film that the police present need to uphold “the standards of law and order.” The excitement of the students speaks to the program’s effectiveness. Its national success, in part, was propelled by Vassar College President Henry Noble MacCracken (1880-1970). MacCracken founded the Junior Red Cross of America in 1917. The new organization soon partnered with the NTA, heavily promoting the Modern Health Crusade. Under MacCracken’s leadership, Vassar College became a primary mode of outreach. A notice in the Poughkeepsie Eagle from February of 1919 remarked that Rhinebeck schools received lectures about the Crusade from Vassar’s Four-Minute-Girls, mirroring the wartime Four-Minute-Men whose spoke about war effort. Dutchess’ Collegiate involvement also spread nationally as NTA targeted Vassar seniors for executive positions at their headquarters in Philadelphia and as nurses throughout the country. By 1930 however, deForest and

Posted in: Decoding Dutchess Past, Decoding Dutchess Past, For everyone