Two Rhinebeck Houses Reflect Opposing Political Views in 1860

By Bill Jeffway

A study of two houses across the street from each other in Rhinebeck, and the politics of their owners, is a study in the politics of our early republic in the run-up to the Civil War and the split in the north within the Protestant White establishment. Their opposing involvement in the 1860 US Presidential election, and some local actions and words of Abraham Lincoln, offer insight into the divisions in the country, and Lincoln’s “team of rivals” approach to reconciliation.

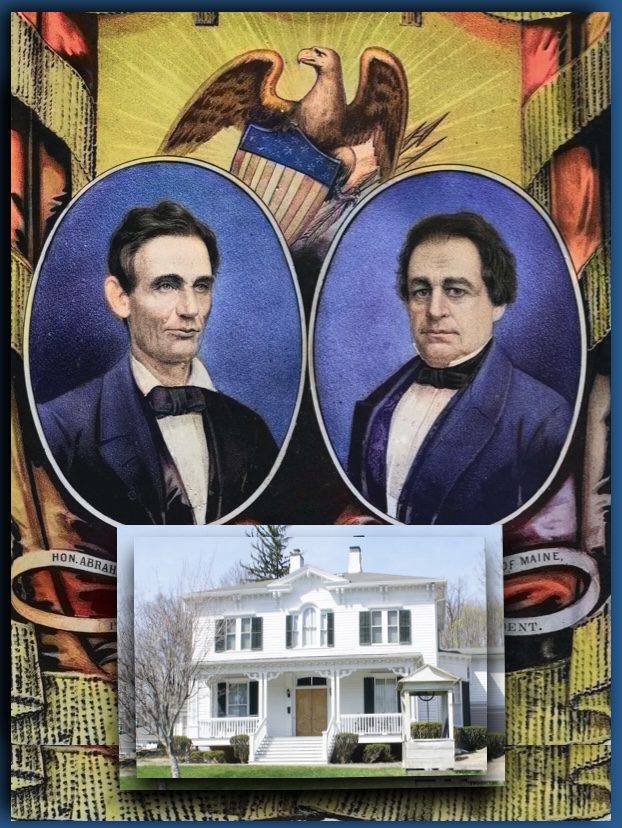

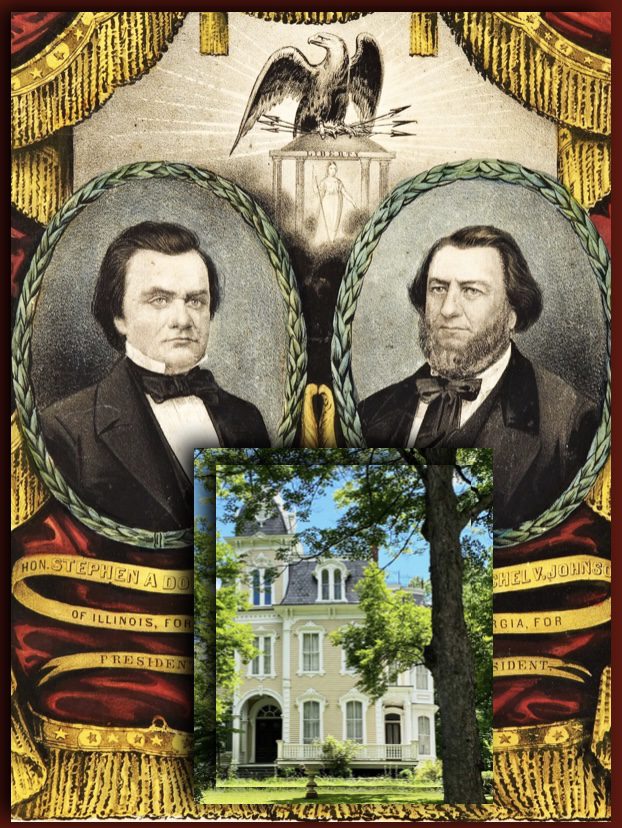

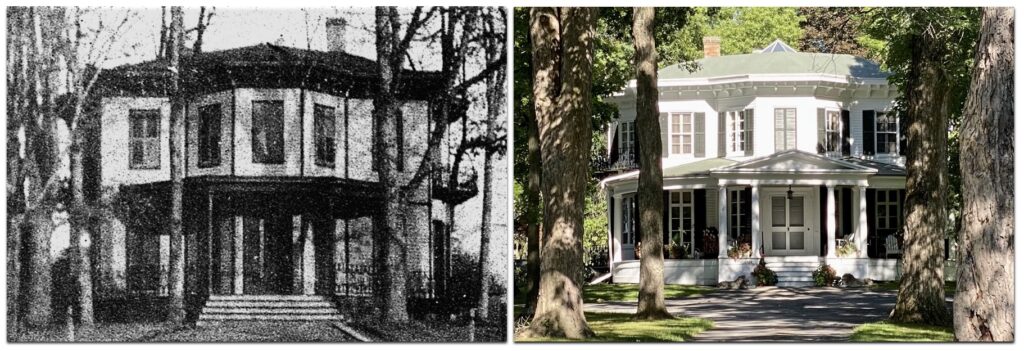

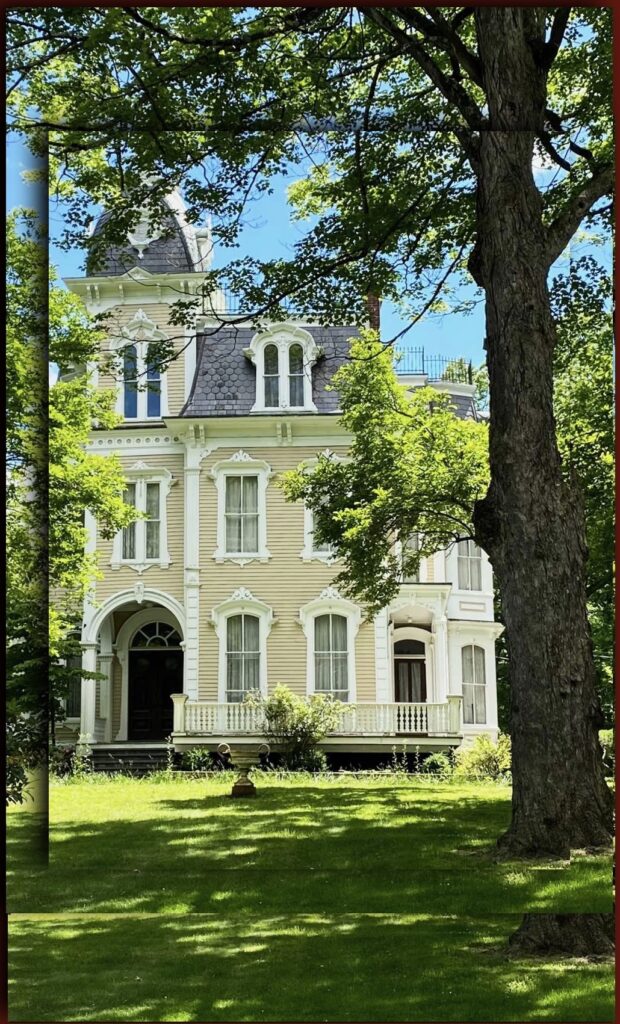

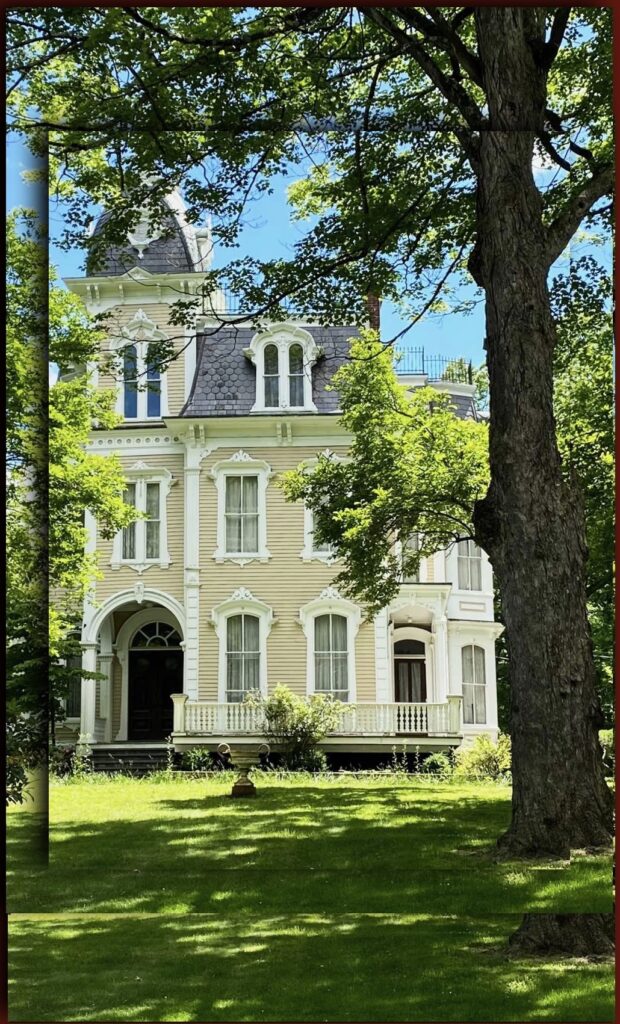

Although in 1860 Ambrose Wager was living north of Rhinebeck Village on Montgomery Street in a house that stands today (see photo), he is best known for his Second Empire house on West Market Street that was constructed in 1874. Slightly younger than Darling, Wager built the monumental West Market Street house at the peak of his life’s achievement, as was the case with Darling when he built his West Market street house in the 1850s.

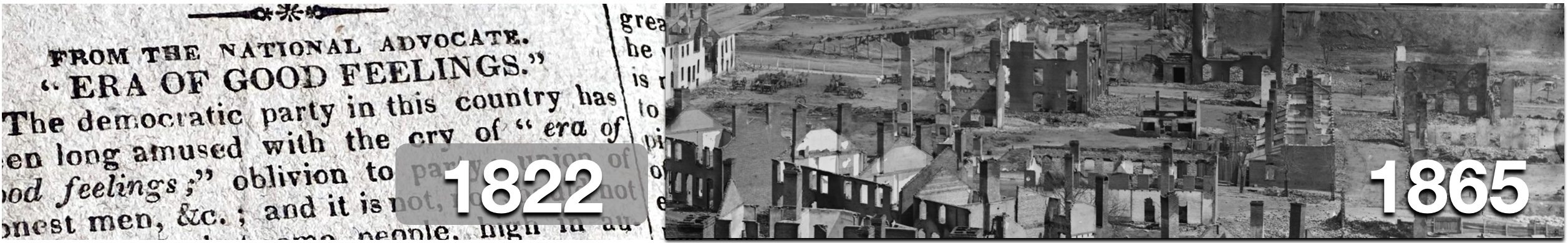

From Era of Good Feelings to Civil War in a Generation

Local newspapers in Dutchess County, and around the country in 1817 were describing what they saw as an Era of Good Feelings in the country where political divisions were put aside. The name and concept took hold, and the era is seen by historians as aligned to the Presidency of James Monroe, from 1817 to 1825. But in little more than a generation, between 1861 and 1865, the Civil War caused the deaths of 2% of the US population, the equivalent of 7 million people today.

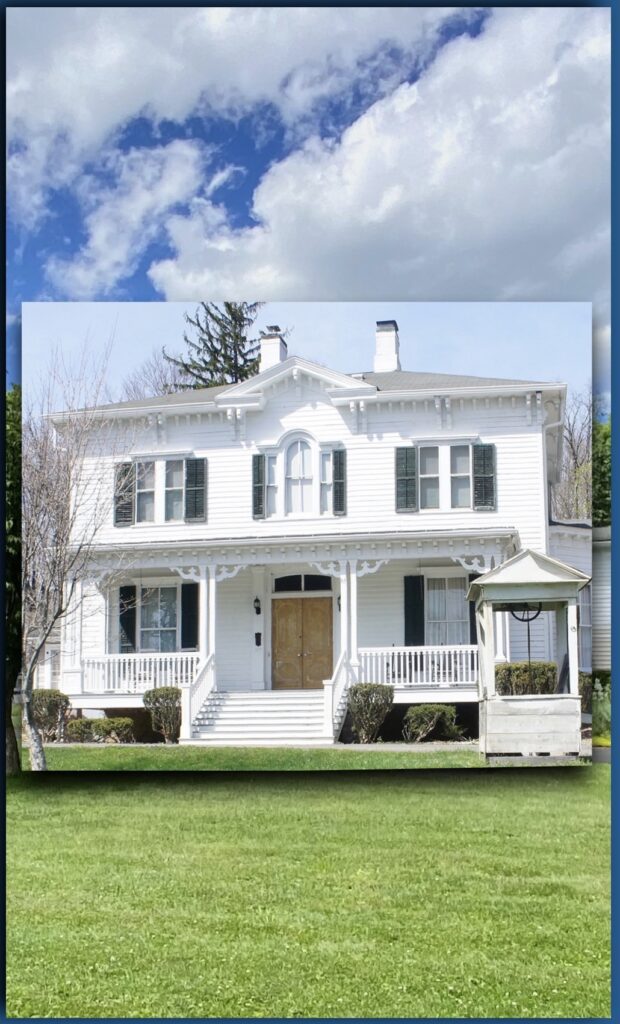

Nathan Darling chose Hudson River Bracketed Style

Nathan Darling had built the house that stands today on the north side of Market Street by 1858 in a classic, local style described as Hudson River Bracketed by the local architect of national influence Alexander Jackson Davis. It was a style designed by Davis that could be embraced and executed by the average working class, as well as the elite, and everyone in-between. Although never a political candidate, the 1860 Federal census description of his occupation as “politician” is appropriate given the path he took to become a “wide-awake” leader of the Republican party.

Ambrose Wager chose Second Empire Style

On the south side of West Market Street stands the home of Ambrose Wager, an imposing Second Empire style home reaching back to Napoleonic France for inspiration built in 1874. Its imposing grandeur and connotations of Empire give it an immovable feeling. Wager’s 1883 obituary describes him as a steadfast and unwavering “Democrat of the old school.” The Democratic Party of that time was associated with a more permissive approach to slavery and its expansion. Wager was the 1860 candidate for Congress for the Democrats.

Darling was active in politics all his life. In that transitional period between the era of good feelings and the Civil War, he got involved in a wide array of political movements that splintered and coalesced and splintered and coalesced again. The names of the political movements at the time give us a sense: the Locofoco’s, the Hindoo party, the Barnburners, the Know Nothings, the Free-soilers, the Native American party (referring to European Americans born in this country), the Hard and Soft Democrats.

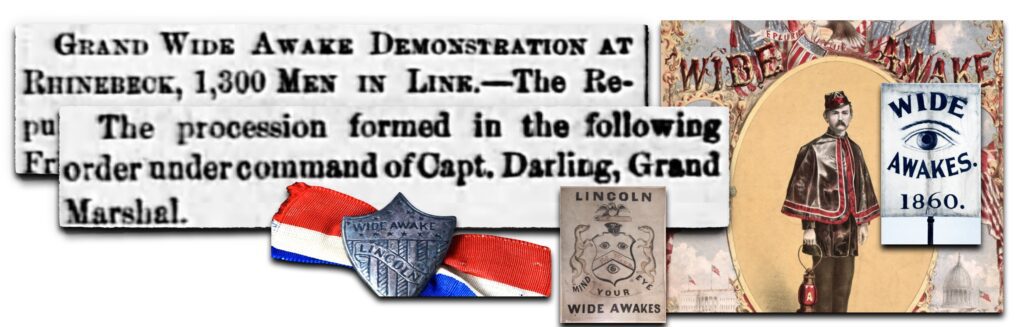

That splintering started to recede as the newly formed Republican Party emerged in 1854, a party with anti-slavery sentiments. By the 1860 Presidential election the Republican party had matured and Lincoln emerged as the party leader. Going further, however, within this movement, there emerged locally and all across the north, the most visible agitators for Lincoln who became known as the Wide-Awakes. The name was meant to reflect the depth of their commitment, and the level of energy they brought to the cause. Given the nimbleness of Darling’s prior political maneuvers, it is not surprising he became the visible leader of that movement in northern Dutchess County.

Here is a description of a Rhinebeck parade from the November 3, 1860 Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, “Grand wide-awake demonstration at Rhinebeck. 1,300 men in line. The Republicans of Rhinebeck had a grand time last evening. The parade of the wide-awakes was far ahead of any political procession ever seen before in this town. The clubs from Poughkeepsie were on hand headed by Flockton cornet band and were honored with the right of the line. The procession formed under command of Captain Darling Grand Marshal. Almost every house in the village was illuminated in the enthusiasm of the spectators and was unbounded as a political demonstration. It was most successful and showed most conclusively that the Rhinebeck Republicans are wide-awake for the cause.”

As the Republican candidate, Lincoln won the November 1860 Presidential election without winning any southern state. And while he won all northern states, except New Jersey, you need only look at Dutchess County election results to see the choice was far from a mandate in the North. While Lincoln carried the county overall, he did not carry East Fishkill, Fishkill (Beacon), Hyde Park, LaGrange, Red Hook, or the Town of Poughkeepsie. Lincoln won the electoral college with only 39% of the popular vote.

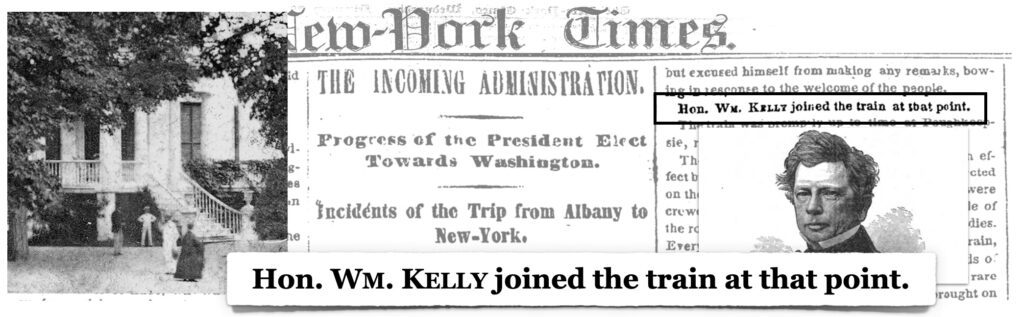

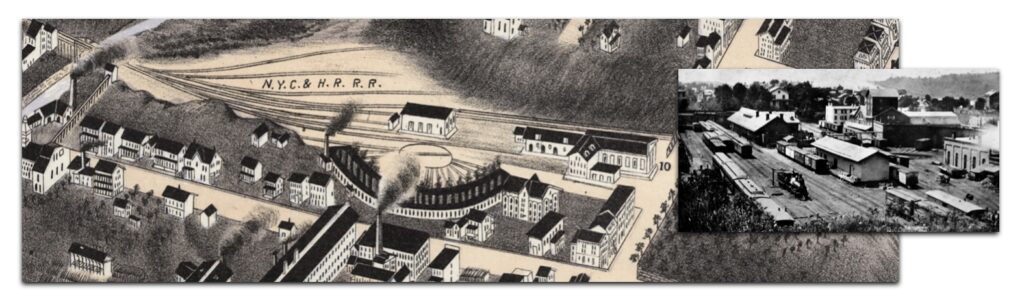

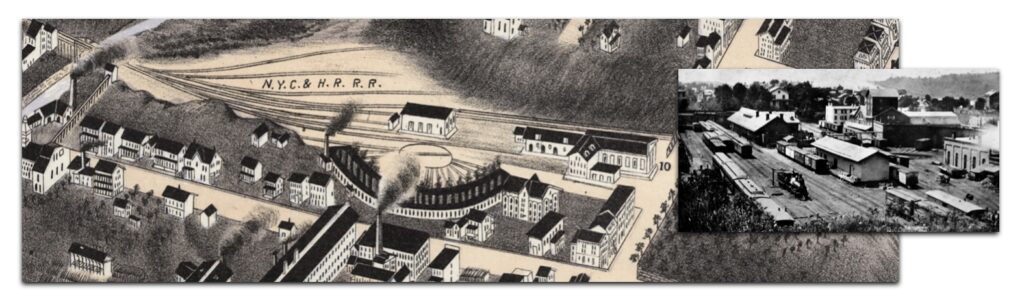

Lincoln inaugural train stops in Rhinebeck

This was the divisive backdrop to the inaugural train journey from his home in Springfield, Illinois to Washington DC where he would take the oath of office that included Lincoln, Mrs. Lincoln, their three sons, and Lincoln’s African American servant William Johnson. Lincoln had stopped in Albany overnight and was on the next leg of his trip when he stopped briefly in Rhinebeck. Lincoln is described by viewers as having bowed, but not spoken to the crowd. The New York Times reported that Lincoln picked up at least one person, specifically William Kelly, of Rhinebeck’s Ellerslie Estate. Kelly had just run for, and lost the NY Governorship candidate from in the Democratic Party. This kind of outreach is typical of Lincoln’s “team of rivals” embrace. Ambrose Wager was the (also failed) Democratic candidate for congress in the 1860 election.

Lincoln speaks in Poughkeepsie about what to do when we lose

Lincoln did take just a few minutes to speak in Poughkeepsie at the train station. The few words the President-elect spoke were about going beyond partisanship to save our government institutions, and the need to support the office of Chief Executive, regardless of the popularity of the individual person occupying it at any given moment. He stopped for literally a very few minutes, saying the following in Poughkeepsie:

“I cannot expect to make myself heard by any considerable number of you, my friends, but I appear here rather for the purpose of seeing you and being seen by you. (laughter). I do not believe that you extended this welcome, one of the finest I have ever received, to the individual man who now addresses you but rather to the person who represents for the time being the Majesty of the Constitution and the government. (Cheers.) I suppose that here as everywhere you meet me without distinction of party but as the people. (Cries of yes, yes.).”

“I see that some, at least, of you are of those who believe that an election being decided against them is no reason why they should sink the ship. (“Hurrah.”) I believe with you, I believe in sticking to it; and carrying it through; and if defeated at one election, I believe in taking the chances next time. (Great laughter and applause.)

I do not think that they have chosen the best man to conduct our affairs, now–I am sure they did not –but acting honestly and sincerely, and with your aid. I think we shall be able to get through the storm –In addition to what I have said I have only to bid you farewell. (Cheers and a salute, amid which the train moved on).”