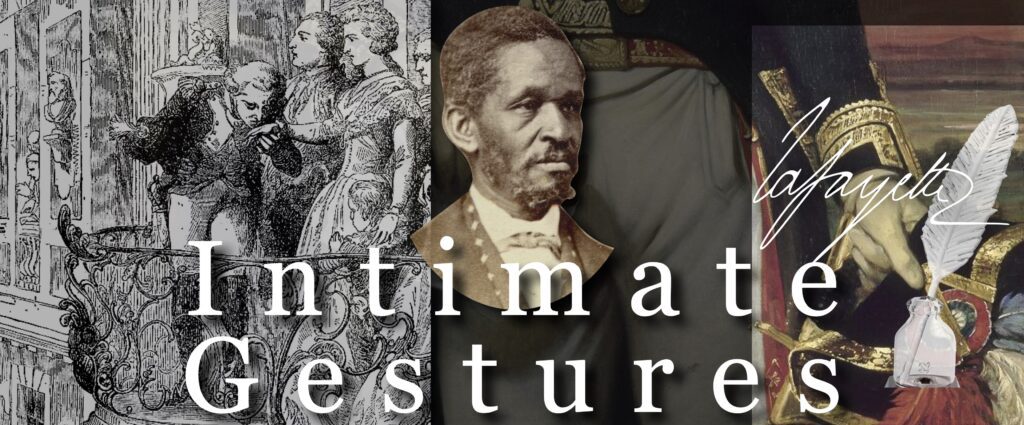

Big Moves & Intimate Gestures.

Why Lafayette’s approach to equality has meant so much to so many.

Below is a continually evolving concept that looks at Lafayette through the hearts & minds of those in his 1824 diverse, record-size audiences (and later audiences well into the 20th century) who were at greatly varying degrees of success in realizing the American promise of equality.

An in-depth look here:

Click full screen icon bottom-left for best view

A quick summary below:

September 16, 2024 will mark the 200th anniversary of Lafayette’s visit to Dutchess County’s Poughkeepsie and Staatsburg — and Columbia County’s Clermont and Hudson. September 19 will mark the same anniversary for his visit to Red Hook and Fishkill Landing. Part of a 13-month tour of all 24 states, he was the “nation’s guest” at the instigation of President James Monroe, at the invitation of Congress. They sought to rally and unify the country as it approached its 50th anniversary: July 4, 1826. Monroe’s sense that time was running out was prescient. Both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died on that day. Monroe died July 4, 1831. Lafayette died in 1834 in France. Called a man of two worlds because of his role in the 1776 American Revolution and the French Revolution at the end of the following decade, he was only 19 years old when Congress made him a Major General. In addition to citations for bravery and effectiveness in the military, he contributed his personal wealth, and persuaded the King of France to formally and actively support the American cause.

A firm commitment to truth.

Big moves & intimate gestures.

Toward the end of his life, Lafayette called for a strict adherence to truth. He said that moderation is not the average between two points, but a firm grip of the truth. “When it is said that four and four make eight and an extravagant person pretends that it makes 10, is it more reasonable to maintain that four and four make nine? No, true moderation is discovering what is true, and firmly abiding by it.” Nowhere is this more evident than his views and actions and commitment the idea that all are created equal. To Lafayette, all meant all.

In Lafayette we find a very distinct combination of big moves, such gaining the support of France in the American cause, or his own personal support of the same, and small gestures, like kissing the hand of Marie Antionette to calm an angry crowd, or the tip of his hat to an enslaved Kentucky boy (Lewis Hayden shown above) who said that inspired him to become the nationally known abolitionist that he was.

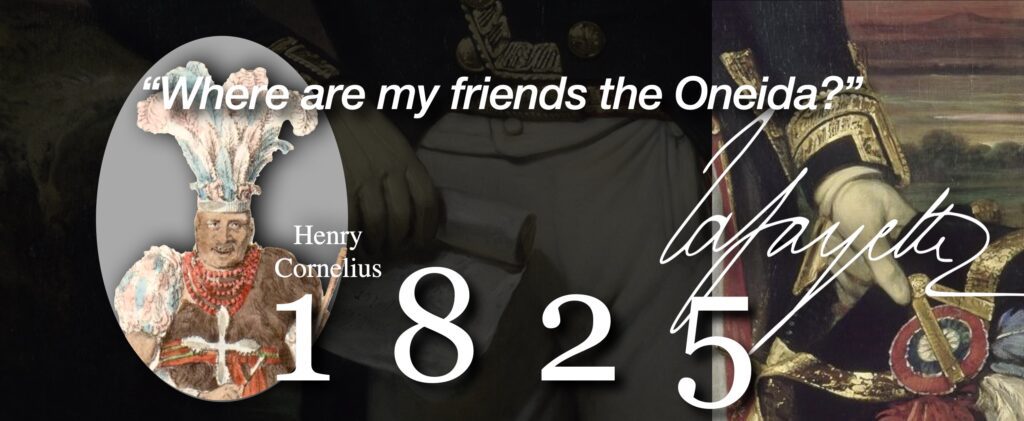

American Indians. Big moves: Lafayette assisted the Oneida Nation, America’s ally during the Revolution, with fortifications of their settlement and persuaded them to send 47 of their soldiers to join the Continental Army. They gave him the name Kayewla, or Great Warrior. Small gesturees: Not seeing any Oneida on his June 10, 1825 visit to Utica, a former Oneida stronghold, Lafayette asked his hosts about them, surprising them with the request. When the Oneida came, they had a private audience with Lafayette that he had not granted others.

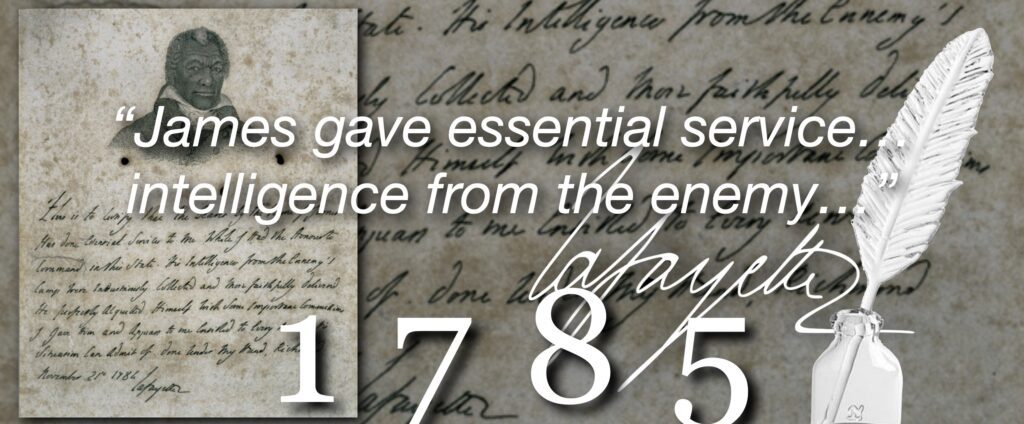

Free and enslaved Blacks: Big moves: Lafayette enlisted James Armistead, an enslaved man in Virginia who had earned a temporary reprieve from his owner, to became an invaluable double-agent spy, infiltrating the highest levels of the British military. Small gestures: but was returned to being enslaved at the end of the war and was denied a pension for lacking a combat role. Lafayette successfully personally petitioned congress on both accounts.

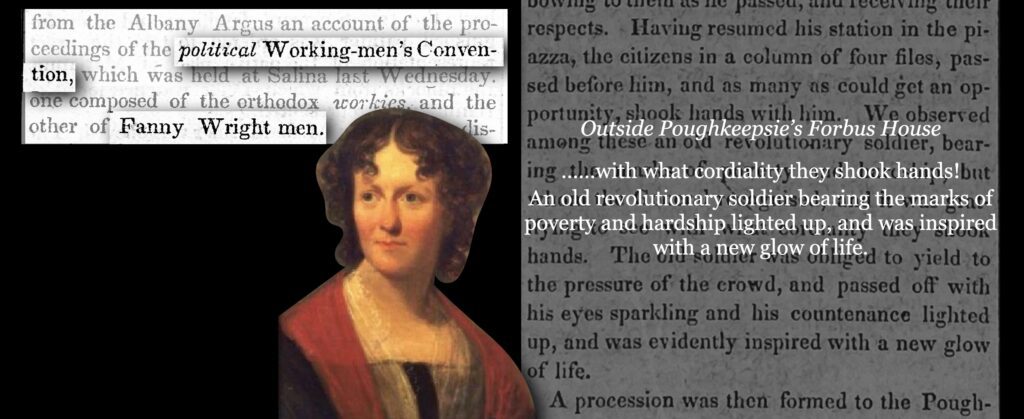

White working-class and poor: Big moves: There is less of a direct connection, but an important one nonetheless. For much of his tour, Lafayette travelled with a close friend, Frances “Fanny” Wright. Within a few years, she be so aligned to the Working Men’s Party that the party became known as the Fanny Wright party, and its candidates Fanny Wright men. Small gestures: The Poughkeepsie Telegraph reported that at Forbus house, “We observed among [the crowd] an old revolutionary soldier bearing the marks of poverty and hardship, but whom the general recognized. And it was gratifying to see with what cordiality they shook hands. The old soldier was obliged to yield to the pressure of the crowd and passed off with his eyes sparkling and his countenance lighted up, and was evidently inspired with a new glow of life.”

Fanny Wright became close to Lafayette immediately upon meeting him in France in 1821. She travelled with him on a good portion of his 1824/1825 tour including a stay with Jefferson at Monticello. She went on to become associated with the Workingmen’s Party. Lafayette penned a successful letter of support in James Armistead’s request for freedom, which had prior been denied. When Lafayette arrived in Utica in 1825, he insisted the Oneida be invited, who he granted. aprivate audience.